People

For complete rosters of the personnel of Base Hosptial 31 and Base Hospital 32, see the unit histories.

Florence V. Martin

Florence V. Martin, Chief Nurse of Base Hospital 32 (image captured from eBay)

Amy Beers, Assistant Head Nurse of Base Hospital 32 and Head Nurse of Unit R (image courtesy of Jefferson County Health Center, Fairfield, IA)

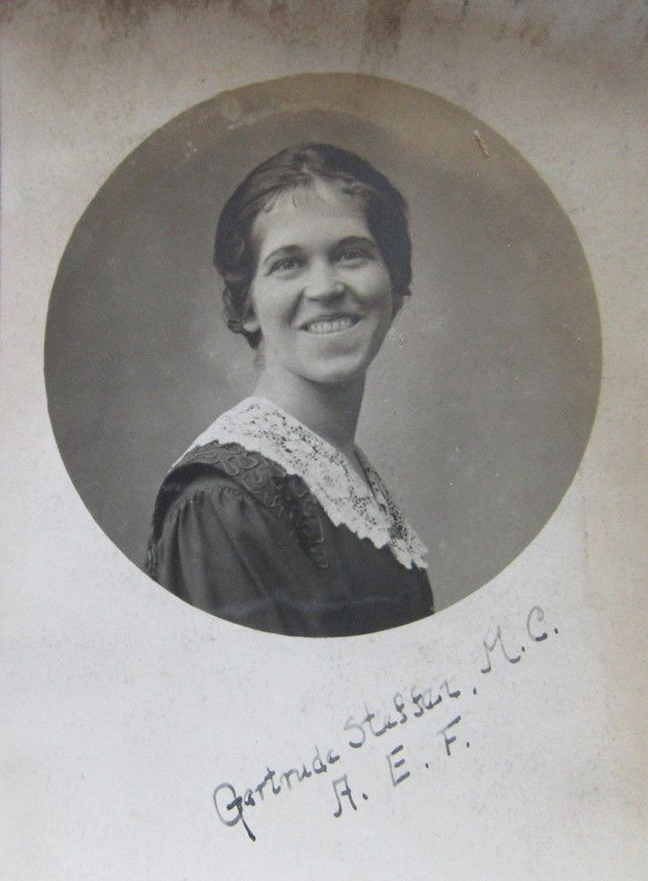

Gertrude Steffen, from Indianapolis; civilian employee of Base Hospital 32 (Stenographer) (image captured from eBay)

Charlotte Cathcart

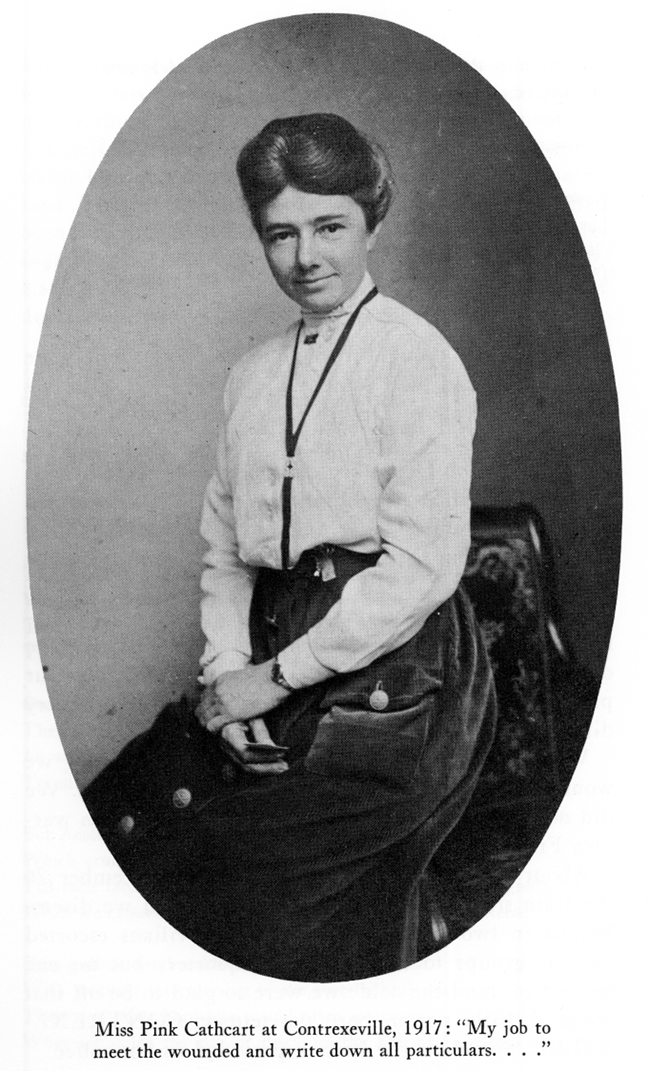

Charlotte Cathcart, Indianapolis; civilian employee of Base Hospital 32 (Stenographer) (image from Indianapolis from Our Old Corner, by Charlotte Cathcart).

Charlotte Cathcart, Indianapolis, 1901; civilian employee of Base Hospital 32 (image courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, P0434)

Agnes Swift and her father, John C. Swift, Washington, Iowa, 1906. Agnes's father died while she was serving overseas with Base Hospital 32 - Unit R in Contrexeville. (image from private collection)

Kathryn Olive Graber, Burlington, Iowa; nurse with Base Hospital 32 - Unit R (image from the Iowa State Historical Society, Iowa City)

Grace van Evera, Davenport, Iowa; nurse with Base Hospital 32 - Unit R (image from the collections of the Iowa State Historical Society, Iowa City)

Maude Essig, Indianapolis; nurse of Base Hospital 32 (image from the Tate Archives & Special Collections, The Ames Library, of Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL)

May Berry

May Berry is one of two AEF nurses who served in Contrexeville who are buried overseas (the other is Dorothy Millman, with Base Hospital 31). Lottie May Berry was born in Dunreith, Henry County, Indiana in 1888, and died Dec. 20, 1917 at Brest, France. She was assigned to Base Hospital 32 in Contrexeville, but she never reached her final duty station. She fell ill with pneumonia during the voyage from New York. She was initially buried at Kerfautras Cemetery in Brest, France, and then later reinterred in the Oisne-Aisne American Military Cemetery at Fere-en-Tardenois, in Aisne, Picardie, France. (image from May Berry's Find-a-Grave.com memorial.) Click here for a full bio, as provided by Larry Hume.

May Berry, nurse with Base Hospital 32, died of pneumonia shortly after the unit reached France.

Dorothy Millman

Dorothy Millman from Youngstown, Ohio, was working at Base Hospital 31 but became seriously ill and died while under treatment for a gall bladder infection. She was initially buried in the American sector of the Contrexeville cemetery (the only AEF nurse buried there) and later reinterred for reburial at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, where she rests today. Click here for a full bio, as provided by Larry Hume.

Dorothy Millman

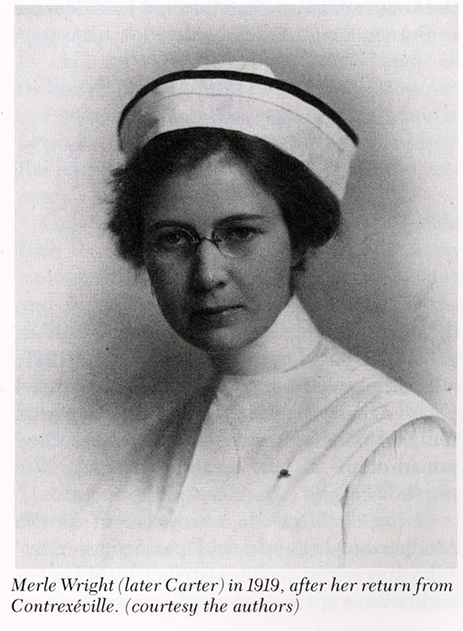

Merle Wright Carter, Wright, Iowa; nurse with Base Hospital 32 - Unit R. She is believed to have been the last surviving member of BH 32 personnel when she died 5 days before her 96th birthday in 1988.(image from the September-October 1968 issue of the Palimpsest, publication of the Iowa State Historical Society.)

Capt. Arthur E. Guedel

(Dr. Guedel responsible for introducing two innovations in anesthesia to medical practice during WW I)

[from Hitz, p. 141 and 142]:

It was in Base Hospital 32 and the Vittel Medical Center that a combination of ethyl chloride, chloroform and ether, administered under a closed hood, was developed for all short operations and general induction of all ether anesthesias.

In Base Hospital 32 there was developed another novelty in anesthesia which was a general improvement over previous methods. This was the adaptation of an auscultation tube to a simple apparatus for the par nasal intrapharyngeal administration of ether. This auscultatory tube aided in the determination of the degree of anethesia present in any case without necessitating the close inspection of the face of the patient, which, in head surgery, is usually well covered by sterile draperies, and inaccesssible without disturbing the field of operation.

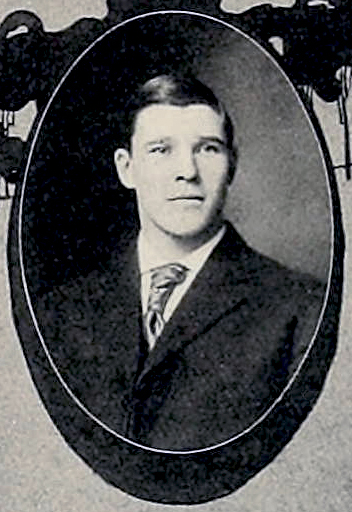

Capt. Arthur E. Guedel, anesthetist for the Contrexeville-Vittel hospital center (image from the 1908 Purdue University yearbook, Ancestry.com)

Pauline Thouvenot

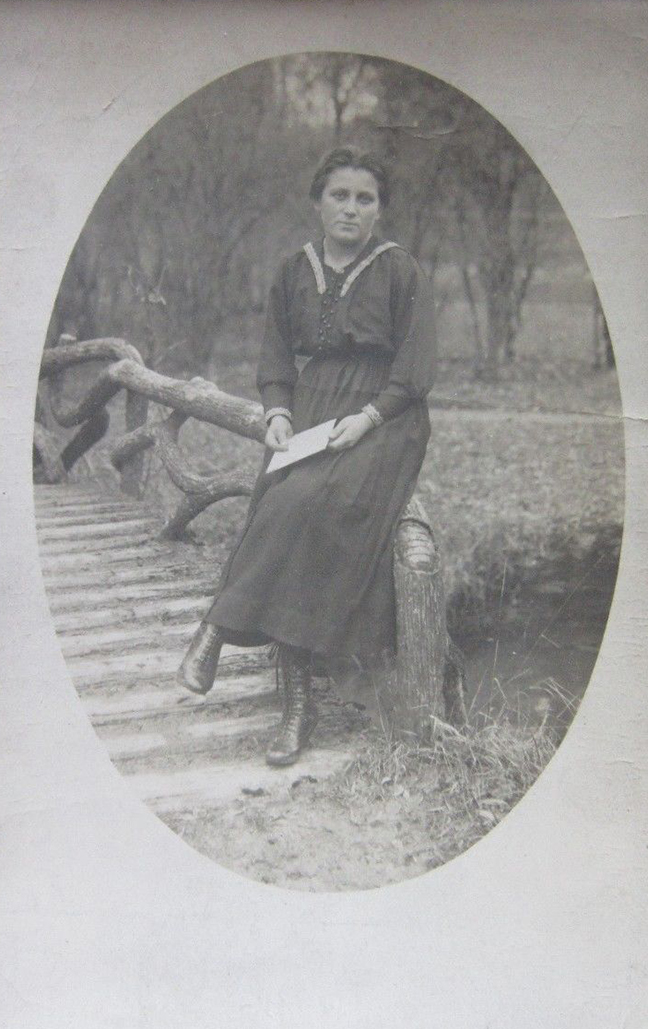

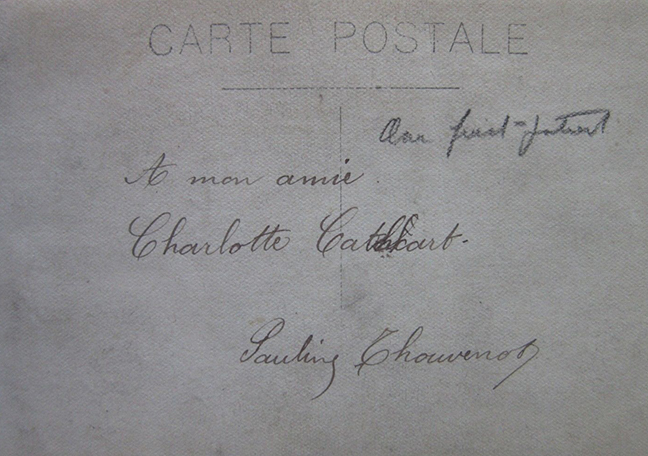

Image on postcard mailed to Charlotte Cathcart from Pauline Thouvenot (presumably a Contrexeville resident). The back of the card conveys greetings to Miss Cathcart and includes the notation "our first patient." (image captured from eBay)

Message on the backside of the card mailed to Charlotte Cathcart. (image captured from eBay)

Lace maker, Contrexeville (image from the unit history of Base Hospital 31)

Madame Harmand and Monsieur Harmand

She is the village Lady Bountiful and he is her knight. Do not presume that she is a lady of silks and velvets, glistening heels, gold lorgnette and coach and four. Really she is quite an old lady. She and her husband own one of the largest of the group of summer hotels in Contrexeville, which, during four years of the war was used as a hospital, three years by the French and one by the Americans. Madame Harmand heads this list because not a patient, enlisted man or officer, ever came in contact with her without saying soon afterward – “There's a thoroughbred,”, or words to that effect.

Once upon a time she was strikingly beautiful. Her skin to-day is like parchment with still a trace of the color of another day. Her hair is quite gray. Her eye is the same deep blue as of yore and it has the same sparkle. And when she speaks to you in her perfect French she speaks so slowly and distinctly and with such a wealth of tone and eloquence of gesture that you understand her even if you do not understand what she is saying.

She is the "Lady Bountiful" because she is the one person in the village to whom the poor and afflicted look for assistance in time of need. Are the Americans foolishly on the point of throwing away a pile of splintered lumber? Madame Harmand will see that the poor get it. Does Lisette need a doctor? Madame Harmand will arrange to have Dr. Bunn see her. Is Private Bill Jones down on his luck, and down in the mouth and homesick? It is the miracle working Madame Harmand who looks out of the window as he passes, and smiles upon him with a most motherly smile and bids him enter. Entering, Bill Jones finds a wedge of cherry pie. Truth to tell it isn't as good as mother used to make, but mother will have to bear up under the truth when I tell her that Bill appreciated it more than any she ever made him.

And Monsieur Harmand: The Americans knew him less because he liked to have the Madame keep the center of the stage. And he spoke his French somewhere about twelve degrees below his larynx; perfectly impossible to understand him. The boys learned to know and respect the old gentleman with the huge shaggy head and the badly bent back. I, at least, never will forget my first view of him. He wore a gingham apron, and wooden shoes. He was smoking a powerful pipe ·and was pushing an ancient wheelbarrow and I thought he was the janitor of the building. He was, right enough, but he was the proprietor, too.

Most of us have said that some day we shall come back to Contrexeville, to see it in gaiety rather than in sadness. Every last one of us has promised to call on the Harmands. Also, all too few of us can keep the promise, but they shall dwell forever in our memory.

From Kaletzki, Charles Hirsch. Official history USA Base Hospital No. 31 of Youngstown, Ohio: And Unit G of Syracuse University. Syracuse, NY, Craftsman Press, 1919, pp. 219-220

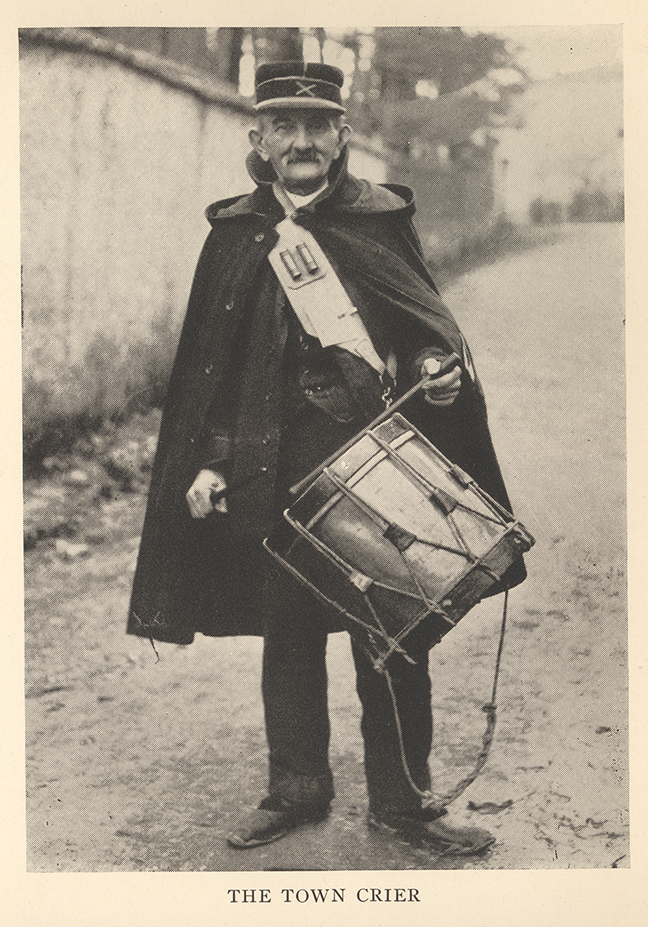

Town Crier - Alfred Cordier

Town Crier (image from the unit history of Base Hospital 32)

Avis!!

Rum-a-tum-tum-tum-tum-tum-tum.

All the housewives are looking out from their windows, the youngsters gather around, the butcher has stepped into the street, wiping his hands on his apron. The ancient dame in the cafe has left her customers. A withered old man dressed in a Napoleonic uniform, weighted down with an immense drum and a full appreciation of his importance, stands in the middle of the road. All traffic-American included-has ceased. The town-crier has an announcement to make.

“Avis!” he cries.

He draws from his belt a carefully folded sheet of paper, carefully unfolds it, and in accents utterly incomprehensible, even to some of the natives, he reads that the Mayor says that the populace from now on can have two pounds of potatoes, or that all dogs must be muzzled. The reading over, the paper is folded again and replaced. Follows then one tap of the drum. If another announcement is to be made the entire proceeding is repeated.

Then he limps along to a point about a hundred yards down the road and repeats all his announcements.

Time was when the Americans used to ask the old fellow what it was all about. He used to try to explain, never successfully. Concluding finally that we were all hopeless dullards, he adopted the policy of telling us nothing or at most: “Pas grand chose!”[not much]

[Kaletzki, p. 220-224]

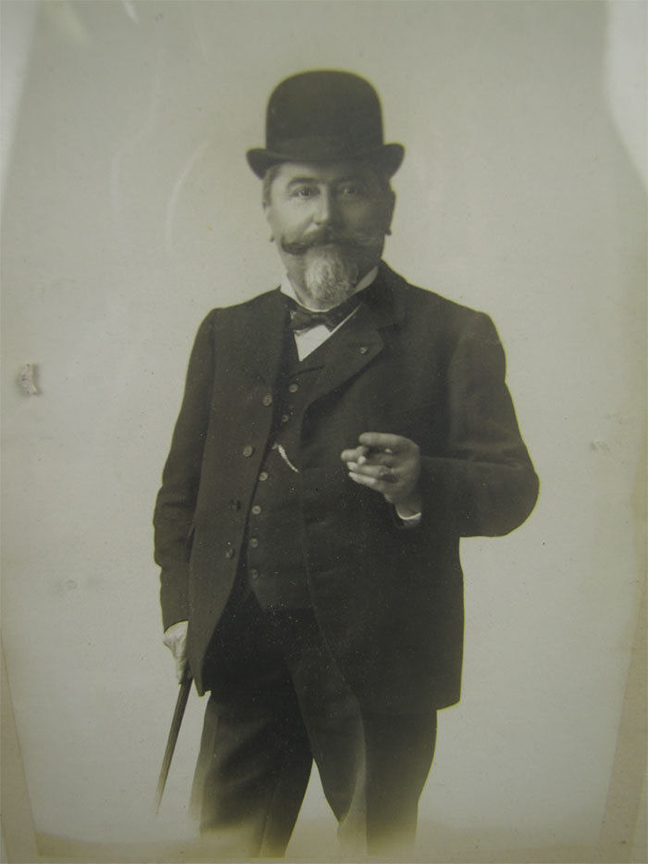

Mayor of Contrexeville, Monsieur Auguste Morel

The Mayor of a French town is “no small shakes,” as one of our boys from Ohio said one day. The Mayor of Contrexeville is a distinguished appearing old gentleman who dressed always in black broadcloth and colored spats, except when he wore an alpine uniform with golf stockings and a feather in his hat. He is an austere person, both feared and loved by the villagers, thoroughly respected by all the Americans and genuinely admired by the few who knew him. He lives in the finest house in the village, set upon the top of the highest hill.

On Memorial Day, July 4 and July 14 he took an important part in the ceremonies, always delivering a speech, and a good one too. He attended the exercises, dressed in his usual faultless broadcloth, augmented by his official emblem of office, a tri-color ribbon sash worn over the shoulder. He endeared himself to the American soldiers on July 14 when at the close of the military exercises in the square he broke the stiff solemnity of the occasion by waving his hat in the air and crying with contagious impetuosity, “Vive l'Amerique! Vive La France!”

[Kaletzki, p. 224]

Monsieur Morel, Mayor of Contrexeville (image captured from eBay)

Pere Brossard

Back a few centuries in the days when the fountain head of all activities, social, political, educational, as well as ecclesiastic, centered in the church, a Bishop with an eye for the beautiful caused to be erected in a vale not far from Contrexeville a monastery. Perhaps there is a bit of irony in it, but we of Contrexeville knew it well-sometimes too well, alas-but never as a monastery. The Bishop's Farm was always our one sure-fire asylum from “the horrors of war” and Pere Brossard with his wife, his dogs and his omelettes was the sacrilegious successor of the ancient clerics.

It was a pleasant half hour's walk-in fair weather-along the aspen bordered Suriauville road and then down the wooded lane to where the red-roofed old retreat looked out upon miles of meadows and forest. There one heard, in spring, the haunting call of the cuckoo and at late dusk the heavenly song of the nightingale. Pere Brossard, dressed in corduroys, leather leggins and a modern cap, usually greeted us as we mounted the terrace. His sole-leather skin wrinkled in smiles when he recognized us. He differed little from his countrymen in his attitude toward the Americans’ francs, but he and his robust young wife had the faculty of making you feel that even if you were dead broke you might eat a “sanglier” chop and drink a bock of Graves superieur.

When his guests were not too numerous Pere Brossard used to like to lure us away from his trashy parlor with the nickel-in-the-slot piano, down through the spacious kitchen with its odd assortment of open fireplaces and toy ranges, down into the barns where dwelt sheep, goats, cows and horses. If you knew this Vosgien Boniface real well he would take you down further, into the damp cellar where in the hesitant flicker of his “lampe pigeon” you saw veritable walls of bottles, many of them half buried in earth. And on one memorable night when a group of officers having their first holiday out of the lines had without authorization absented themselves from the hospital and were enjoying a feast of broilers and waffles, old Father Brossard and I solemnly knocked the head from a bottle which he vowed was thirty years old. It was Burgundy, rich, mellow, deep-toned, warm-blooded Burgundy. And how he smacked his lips over it!

We were a veritable godsend to the Brossards. In other days their dining room and dance hall were always crowded with the visitors who had been gathered from all parts of Europe to drink the waters of Contrexeville and Vittel. Many a world celebrity has eaten wild boar and drunk Burgundy at “La Ferme des Eveques.” But during the war they did not come and the Brossards, although they said frequently that we were lacking in the niceties of appreciation-that an ordinary Chablis to our taste was as good as a Chateau Yquem-the Brossards, I say, were always mighty glad to see us, even in the days when we had to bring our own bread and sugar.

[Kaletzki, p. 224-225]

Pere Brossard, niece and dog. (image from the unit history of Base Hosptial 31)

Pierre

“’Ailo, Buddie!”

The years will glide by as the milestones glide by along the highways of steel and ballast, and Contrexeville will grow dim in our memories even as the milestones grow dim in our eyes-but never will we forget Pierre. Pierre with his laughing blue eyes, his round head crammed full of old thoughts, his feet made awkward by wooden-soled shoes, his odd aprons and his French tam-o-shanters. We never knew him except as Pierre, and when we wanted to refer to his mother's bakery we always spoke of “Pierre's mother's bakery.”

He was the first among the youth of Contrexeville to make friends with us. As we sat on the benches in front of Madame Harmand's window--or in front of the spunky Terrache's barber shop, it was Pierre who said, “’Ailo, Buddie,” or “’Ailo, Jean Jacques,” or “’Ailo, George LeRoi.” It is not difficult to recall the early days when we stood retreat, first in front of the Harmand and then in the colonnade. Then Pierre and his friends took up a position opposite the buglers, and every note of the difficult calls was repeated in a voice that mocked the bugle. We only feigned surprise when we saw Pierre line up all the kids in the village and go through the ceremony of lowering the colors with all the sobriety of a company of “regulars.”

Among the youngsters of Contrexeville Pierre was supreme. Some day perhaps he will be a Senator of France-just as Joe Heffernan predicted.

[Kaletzki, p. 225]

Madame and Monsieur Gerard

Monsieur and Madame Gerard (image from the unit history of Base Hospital 31)

In America he unquestionably would be the head of a Chicago meatpacking company selling everything from quarter-beeves to massage cream, and his wife probably would be gliding along Michigan Boulevard in upholstered grandeur. But in Contrexeville he was simply the butcher, and the village's most progressive merchant, while his wife was the bejewelled and silk-stockinged supervisor of domestic finances and public morals.

Many an American butcher can learn a lesson in appetizing cleanliness from the marble and tile “boucherie et charcuterie” of the Gerards. And how many lessons could Monsieur and his assistants learn from their Chicago colleagues in the utilization of “everything but the squeal.” Their butcher shop-as well as the slaughter house and residence-were next door to the Continental Hotel and the Base 31 mess hall. With thoughts growing less sad in the passage of time we may now recall with what agonized looks we gazed upon the fresh cuts of veal, pork and beef within the Gerard shop while we walked along our bankrupt path to “corned bill and macaroni!”

Monsieur Gerard was butcherish in appearance-which is to say that butchers look pretty much alike the world over-not too fat, but immensely well fed. He looked upon the world with utter complacency and a great deal of dignity. He had good meats and sausages, butter and pates, and he knew they were good and if you wanted them you had to pay the price. On Sundays he appeared in his black frock coat-and on that memorable Sunday when his really beautiful daughter received the First Communion he wore a glistening plug hat.

Madame Gerard always carried her head rather high, and it is not difficult to believe the neighbors when they say that in her girlhood she was quite the most beautiful creature in town. It will have to be admitted that she has grown a little stout, but not unpardonably so, and she never was surprised in garments that were anything but spick and span. Diamonds always dangled in sparkling splendor from her ears, and a heavy gold brooch always registered the unruffled movements of her generous bosom. True it is that in the French cities Americans found a code of conduct which could not be reconciled to American ideas and practices. But in Contrexeville and the thousands of other' French villages there exists an inelastic standard of public morals and private conduct which must call up the days of Roger Williams. And Madame Gerard, whether she chose or no, was the public preceptress.

As she presided at the cash drawer, past which filed all of the meat-eating housewives of Contrexeville, she exchanged a few sentences with each of her callers-sometimes in whispers, and again in easily audible disdain. No family skeletons could rattle in a tune strange to her ears, and the secret hopes and fears of every household were as legible as her well-kept ledgers.

A remarkable family the Gerards–good citizens and exemplary butchers.

[Kaletzki, p. 226-227]

Madame and Monsieur Terrache

Terrache the gaunt -- he of the long legs and long hands and pink beard -- was the village barber. We taught him how to cut hair in the American style. We impressed upon him the vital necessity of sharpening his razors. We lifted him from the despondence of poverty to the insolence of undreamed prosperity. And he maligned us for it. In his unintelligible argot he called us American pigs and professed to scorn our money. We doctored him and his wife and his child and in reward he condescended to treat with us-the untutored, rough-edged spendthrifts from out the brazen West.

But he was interesting and picturesque. We used to marvel at how he could preserve his one blue suit, for it always looked neat and well brushed no matter how many heads he trimmed in a day. No rush of business could prevent him from closing his shop at noon and taking an hour and a half for “dejeuner.” He was independent, he was, and he knew he could get away with it. His idea of humor was to say something disrespectful of an American in the presence of an American and several French customers, and he would say it in a brand of French that no American ever learns thoroughly.

Madame Terrache was not remarkable for her sweetness of disposition. If she had learned in her childhood the value of brushing her teeth occasionally she would have been fairly good looking, for she had a wealth of glorious auburn hair and pretty eyes. But what a tongue! There was a time when the convalescent French soldiers, like the convalescent Americans and British, were given brooms and shovels and put to work on the streets. This was so violently offensive to Barber Terrache and Madame that not only were Americans in danger of going unshaven and unshorn, but the Madame upbraided the poilus for their supine submission to the orders of the vulgar Americans.

How preposterous! How ignoble! How base! To make the heroes of France, the defenders of Verdun, the immortal guardians of the glory of La Belle France, sweep the streets! Never so long as breath remained and a heart beat in the patriotic breast of Madame Terrache! Let the Americans sweep the streets if they must have such silly ideas of cleanliness! We were clean enough before they came, anyhow! But to debase our own poor sick heroes by replacing their beloved rifles with brooms? It must not be! She would see the Commandant I She would see the Mayor! She would write to the Minister of War!

Well, she did not have to write to the Minister of War. The Commanding Officer, while a soldier, was a peace-loving man and knew the Madame's capacity for scorn. The poilus swept no more.

And forever after Monsieur Terrache sneered more eloquently as he rubbed in the lather and Madame-well, Madame lowered her eyelids and raised her chin as she passed us by.

[Kaletzki, p. 227-228]

A veteran of the Franco-Prussian War, Contrexeville, 1918. (image from the unit history of Base Hospital 32)