Formation of Base Hospital 32

Source: Hitz, Benjamin D. A history of Base Hospital 32, including Unit R. Indianapolis, 1922, p. 1-9:

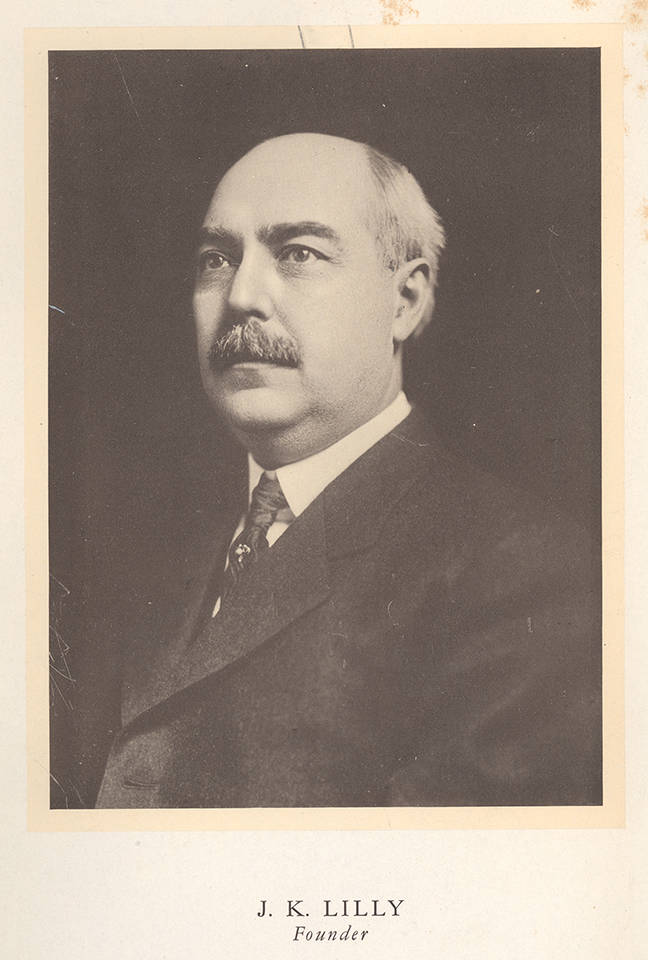

The story of Base Hospital 32 begins early in February, 1917. At this time, with relations between the United States and Germany becoming daily more strained, a certain group of Indianapolis physicians was already resolving to volunteer its services in event of war. The idea of organizing a hospital from Indianapolis began to take definite form on February 19, 1917, when the following letter from Mr. J. K. Lilly was received by the president of the Indianapolis Chapter of the American Red Cross:

February 19, 1917

Mr. William Fortune, President,

the Indianapolis Chapter,

American Red Cross, City:Dear Sir:

We are informed that a committee of physicians of this city and state are now perfecting the organization of a volunteer staff of physicians, surgeons and nurses to serve under the Red Cross in event our country becomes involved in the European war.Having an earnest desire to co-operate to the fullest extent in the work of caring for our sick and wounded soldiers and sailors in the event of war, we offer the sum of $25,000 to the Indianapolis Chapter of the American Red Cross for the purpose of equipping a base hospital in accordance with the specifications of the American Red Cross.

This gift is to be contingent only upon the actual declaration of war, and is made as a memorial to Colonel Eli Lilly, who, as an officer, faithfully served his country on the field of battle.

If consistent with the rules of the American Red Cross, it is requested that this base hospital shall be known as the Colonel Eli Lilly Memorial Red Cross Hospital wherever it shall be located; and in making our offer it is with the hope that it will provide the staff of physicians, surgeons and nurses now being organized in this city and state with an equipment for rendering that service for which they volunteer.

Very truly yours,

Eli Lilly & Company

J. K. Lilly, President

(photo from unit history of Base Hospital 32)

Whereas, the Eli Lilly & Company, of Indianapolis, having offered this chapter, through its president, the equipment for a Red Cross Base Hospital, at a cost of $25,000 in the event that the United States be drawn into the present European war, and on the condition that the required personal service for such hospital be given by physicians, surgeons and nurses of Indiana; therefore, be it

Resolved, That this generous and patriotic offer from the Eli Lilly & Company is hereby accepted; and, be it further

Resolved, That as an evidence of our appreciation for the high spirit which has prompted this gift, this hospital shall bear the name of Colonel Eli Lilly, whose splendid service as a soldier and citizen is worthy of the highest honor that can be accorded him in the annals of American patriotism; and, be it further

Resolved, That the full text of this resolution be engrossed and presented to the Eli Lilly & Company as a further recognition of their loyal and unselfish devotion to the cause of the United States and of humanity.

Indianapolis Chapter of American Red Cross

By William Fortune, President

Guernsey Van Riper, Secretary.

Indianapolis, February 19, 1917

On April 7, 1917, a state of war having been declared between the United States and Germany, the donation became available, and plans for organizing the hospital followed; Dr. John H. Oliver was appointed director, and the Indianapolis City Hospital was designated as the parent hospital. Associated with Dr. Oliver in this early work were Dr. O. G. Pfaff, Dr. David Ross, Dr. Frank Morrison and Dr. Charles F. Neu. Dr. Norman E. Jobes was appointed purchasing agent, and Mr. Louis Lathrop, disbursing officer.

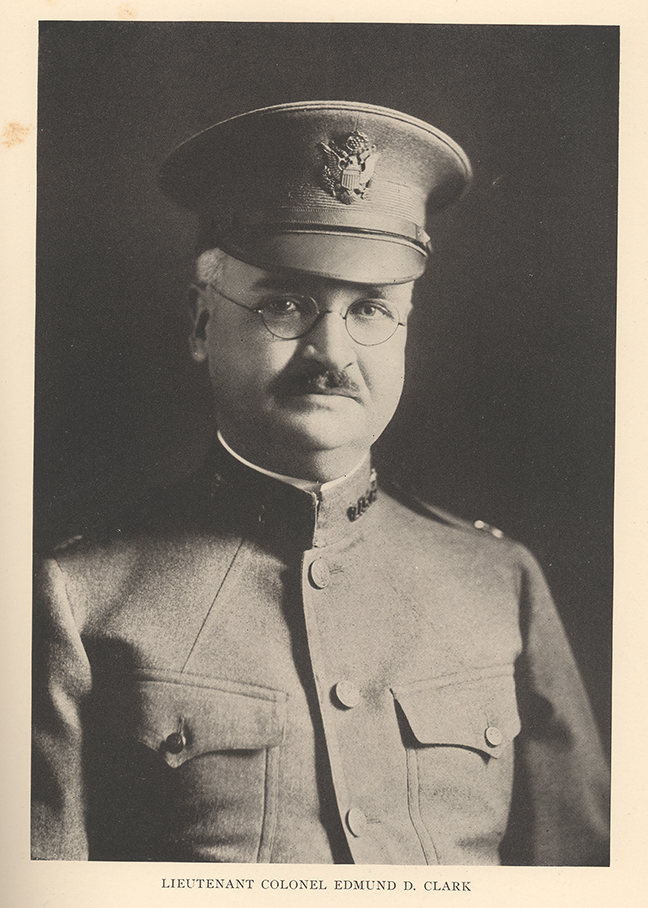

The work of organization was well under way, and many of the most important purchases of equipment had been arranged when it became necessary to make a number of changes in the staff. Dr. Oliver, Dr. Ross and Dr. Morrison were disqualified because of physical disability, and Dr. Neu, who was born in Canada and had never taken out naturalization papers, was obliged to withdraw as he was not a citizen of the United States. Succeeding Dr. Oliver, Dr. Edmund D. Clark was appointed director with the rank of major on June 14th, and it was under his supervision that the work of organization was completed and the hospital prepared for overseas duty. Following the withdrawal of Dr. Jobes, Benjamin D. Hitz was appointed purchasing agent, and Mr. Lathrop was succeeded by C. Curtis Duck as disbursing officer.

The original plan of the Lilly Base Hospital called for a hospital of 500 beds, and the organization of the personnel and the purchase of equipment followed certain definite lines prescribed by the surgeon general's office. The personnel was to include twenty-two physicians and surgeons, two dentists, sixty-five graduate nurses, from six to ten civilian employees, and one hundred and fifty-three enlisted men. Certain alterations of this personnel were subsequently necessary and were authorized, but the general plan was adhered to, and it was with approximately this personnel that the unit sailed for France. The list of equipment for a base hospital of 500 beds published in the United States Army Medical Manual furnished a guide for purchasing. Among the items of equipment were: 500 white enamel beds with full complement of mattresses, pillows and linen, 1,500 blankets, 250 bedside tables, five operating tables, a complete equipment of surgical instruments, X-ray and laboratory supplies, sterilizing apparatus, dental furniture and equipment, three regulation army ambulances, a two-ton truck, and a large assortment of drugs, dressings and minor hospital supplies. As soon as the purchase of this equipment was well under way it became evident that the cost would greatly exceed $2 5,000. The manner in which this problem was met is described in the official history of the Indianapolis Chapter of the Red Cross. ["A Red Cross Chapter at Work," by Marie Cecile and Anslem Chomel.]

It was soon apparent that the cost of equipping the base hospital would be nearer $50,000 than $25,000. In fact, even this revised estimate proved too low. In order to provide for adequate equipment, it was agreed, as the result of negotiations carried on by Alfred F. Potts in July with the officials of the American Red Cross in Washington, that citizens of Indianapolis should contribute $25,000 to the hospital instead of paying it into the national war fund. The national war fund, it will be remembered, was divided between national headquarters and the local chapter, the latter retaining only twenty-five per cent. The arrangement effected by Mr. Potts was a particularly happy solution, especially in view of the fact that two subscriptions amounting to $27,500 had been made at the Indianapolis Club dinner with the understanding that they should be applied to the hospital.

One of these two donations amounting to $15,000, came from Mr. and Mrs. Josiah K. Lilly, further testifying to the interest of the founder of the hospital in the work which it was designed to do.

Early in the summer Dr. Clark, accompanied by Drs.O. G. Pfaff, Carleton B. McCulloch and Bernays Kennedy, all of whom were active in organizing the hospital, made a trip to Washington, Baltimore and New York for the purpose of conferring with Surgeon General Gorgas and with Colonel Jefferson R. Kean, of the Red Cross, concerning certain details of the personnel and equipment. At Baltimore Dr. Clark was in conference with Dr. J. C. Bloodgood, of the Johns Hopkins University, and acquired valuable data concerning the Johns Hopkins Unit, which had already sailed for service overseas. [The Johns Hopkins Unit, Base Hospital 18. sailed for France June 9, 1917. They were stationed at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse. about twenty miles from Contrexeville.] Several base hospitals organizing in New York furnished additional information. It was on this trip, too, that the Lilly Base Hospital was officially recognized and designated as United States Army Base Hospital No. 32.

The selection of Dr. Clark's staff proceeded rapidly and was practically completed by July 1, although many of the commissions were not received until much later. The original staff included Dr. Orange G. Pfaff, chief of surgical staff; Dr. Carleton B. McCulloch, Dr. Alois B. Graham, Dr. Charles D. Humes· and Dr. Eugene B. Mumford; Dr. Bernays Kennedy, ·chief of medical staff; Dr. Lafayette Page, Dr. Ray Newcomb and Dr. Joseph Kent Worthington. Other members were Drs. Leslie H. Maxwell, Paul Thomas Hurt, Smith Quimby, Ralph L. Sweet, Frank C. Walker, Scott R. Edwards, Ralph L. Lochry, Raymond C. Beeler, Robert M. Moore, Elmer Funkhouser, John T. Day and Joseph W. Ricketts. The dental staff was composed of Drs. J. W. Scherer and James V. Sparks.

Miss Florence J. Martin was appointed chief nurse and assisted largely in the selection and organization of the nursing personnel.

The first enlisted men reported for examination May 31, 1917. The number of applicants greatly exceeded the enlisted personnel limit, and the selections were, in the majority of cases, based upon special qualifications. Dr. Carleton B. McCulloch was active in the recruiting and selection of the men, and directed the physical examinations. Enlistment papers were signed on June 15th and 26th, and the men were ordered to be ready for an active service call at any date.

It is interesting to note that the organization and equipment of volunteer base hospitals had been delegated to the American Red Cross, and it was under their jurisdiction that the work of organizing and equipping Base Hospital 32 proceeded. Indeed it was not until September 1, 1917, when the unit was finally mustered into service, that the reins of control passed officially from the Red Cross to the War Department. Until that time practically all instructions relating to equipment and personnel came through Red Cross channels. The director, purchasing agent and disbursing officer were appointed by the American Red Cross, and were responsible to that organization. Monthly reports of disbursements were rendered to the national treasurer, and the purchase of equipment and the organization of the personnel were conducted under Red Cross supervision. The Indianapolis Chapter of the American Red Cross was closely associated with this early work, and the active interest and efforts of its president, Mr. William Fortune, contributed largely to expediting the organization and equipment of the hospital.

Mention should be made here of the splendid co-operation of the Indianapolis Red Cross Shop, which furnished the hospital with a complete supply of linen, bandages and surgical dressings. The Indianapolis Red Cross Shop began its operations early in the spring of 1917 with a small group of women under the direction of Mrs. Philemon M. Watson. Mrs. Watson was succeeded as chairman, July 1, 1917, by Miss Jessie M. Goodwin. The history of this organization, its growth, and the extent of its work, is a story in itself, of which the equipping of Base Hospital 32 is but a part. The total number of articles furnished the hospital. reached 46,371, and included sheets, pillow cases, pajamas, operating gowns, surgical linen, table linen, and an immense number and variety of surgical dressings and bandages. In addition to Mrs. Watson and Miss Goodwin, other ladies who were prominently identified with the hospital equipment work were: Mrs. Robert S. Foster, Mrs. Wm. Pirtle Herod, Mrs. Hugh McGibney, Mrs. Meredith Nicholson, Mrs. Douglas Jillson, Mrs. William L. Elder and Mrs. Thomas Eastman. The vast amount of labor required to produce all this equipment was the result of the combined effort and painstaking work of hundreds of loyal Indiana women. Long before the unit was mobilized every item had been completed, packed in cases for overseas transportation, and stored in a local warehouse ready for shipment.

Mid-August found the unit complete in every detail and eager for service. Officers' commissions that had been sidetracked in their devious journeys through the War Department were finally received. The enlisted personnel had been increased to 180. The work of packing and stenciling the equipment for overseas shipment was being rushed to completion. A few of the officers had already been called out and assigned to different stations for special training; Lieutenant Beeler to New York City for special X-ray work; Lieutenant Edwards to the Rockefeller Institute for instructions in Carrel-Dakin treatment. Lieutenant Quimby to Fort Riley, Kan., and Captain Worthington to Fort Worth, Texas. The vacancy left by the withdrawal of Dr. Ray Newcomb was filled by Dr. Harry F. Byrnes, an eye specialist of Springfield, Mass., who was already on duty at Fort Harrison with the rank of captain.

Rumors were rife that mobilization orders were imminent. Information came that two regular army officers would soon join the unit-one as commanding officer and the other as quartermaster, and that a non-commissioned officer would be assigned for the purpose of drilling the enlisted personnel. On August 15th Captain R. O. Wollmuth, Q.M.C., arrived in Indianapolis and reported to Dr. Clark for duty as quartermaster. Two days later the long-expected and eagerly awaited mobilization orders were received. In compliance with these orders the officers and enlisted men of Base Hospital 32 were to report at Fort Benjamin Harrison, September 1st, for a period of training and instruction. It was announced also that the nursing personnel would probably be mobilized at an early date, and trained at Ellis Island, joining the rest of the unit at the port of embarkation.

The last days of August were marked by great activity. Under the direction of Captain Wollmuth the enlisted men were measured for uniforms. Anti-typhoid and smallpox vaccinations occupied several days. Arrangements for quarters at Fort Harrison, and for the officers' and enlisted men's mess were completed. The army orders of August 24th directed that Captain H. R. Beery, Medical Corps, proceed to Indianapolis to assume command of Base Hospital 32. Captain Beery arrived in Indianapolis on August 27th and Sergeant Peter Pfranklin on August 30th.

It was about this time that additional excitement was injected into the situation when orders were received to ship all equipment to the "Officer in Charge, Port of Embarkation, Pier 41, New York City." Rumors ran riot. It seemed certain that Base Hospital 32 would soon sail. On September 1, 1917, the unit entrained for Fort Benjamin Harrison. The control of Base Hospital 32 passed from the Red Cross to the War Department, and the history of the hospital as a military organization had begun.

Director, Base Hospital 32 (photo from unit history of Base Hospital 32)

Arriving in Contrexeville

Preparations for the reception [in Contrexeville] of Base Hospital 32 on the night of December 25th-26th had been made by Major East of Base Hospital 36, of Detroit. This unit, together with Base Hospital 23, of Buffalo, was already stationed at Vittel, a similar, but somewhat larger summer resort town about five kilometers north of Contrexeville. Temporary quarters had been arranged for and equipped with iron cots and blankets taken over from the French. The first few days at Contrexeville were spent in arranging more comfortable personnel quarters and providing for the mess. Offices were established temporarily in the Hotel Continental, and the Continental kitchens and dining rooms were used until some time after the arrival of Base Hospital 3 I. French rations were provided pending arrangements with the American Quartermaster Corps.

A general plan for the hospital organization, to conform with the buildings provided, was developed by Majors Clark and Beery, but the actual work of cleaning and preparing these buildings for occupancy was delayed by the non-arrival of equipment, and also by the fact that some of the buildings were not yet completely evacuated by the French. The bed capacity, which had hitherto always been figured as 500, was increased by the chief surgeon's office to 1,250, and notice was given that the equipment for the additional 750 beds would follow the shipment of the original 500. In the meantime leases and etat de lieux were signed, and the peculiar intricacies of the French system of renting were explained. In almost all of the buildings certain rooms had been reserved and sealed by the owners for the storage of furniture, and in the case of the Cosmopolitain an additional lease had to be effected to cover the use of the miniature elevator which occasionally could be got to run. The cellars of the Cosmopolitain, with the exception of the kitchens, were also reserved and sealed, and were rumored to contain fabulous quantities of champagne and ancient wines.

A survey of the five hospital buildings showed that they were all wired for electricity and possessed independent water supplies. Most of the buildings were equipped with bathrooms, and the plumbing facilities, as compared with most French hotels, were generally good. All of the buildings had septic tanks draining into tile pipes in the bed of the River Vair.

[Hitz, pp. 47-48]

Continued –

The first steps in organization were the official designation of the different hospital buildings by letters and their division and assignment to the surgical and medical sections. The Cosmopolitain, Hospital A, which was to be the principal surgical building, was to be supplemented by the Paris, Hospital B, an auxiliary surgical hospital which was designed to take care of the overflow from A and to handle convalescent and minor surgical cases. The medical section, with its headquarters offices in the Royal, was to comprise Hospitals C, D and E, the Providence Annex, Royal and Providence, respectively. The pharmacy supplying the medical section was to be located on the first floor of the Providence, together with the medical laboratory and an auxiliary X-ray outfit. A room on the ground floor of the Cosmopolitain was to serve as a hospital supply room for all of the buildings. From here pharmaceutical supplies would be issued to the two pharmacies, and all other supplies issued direct to the individual buildings on requisition.

Practically all of the original equipment had preceded the unit to France, and, with the exception of the truck and the three ambulances, had been forwarded to the Medical Supply Depot at Is-sur-Tille, where it was stored pending the arrival of the hospital at Contrexeville. The truck and ambulances had been unloaded at St. Nazaire, where they were to be claimed and driven overland to their destination. A detail in charge of Sergeant George Swaim was assigned to this task, and the trip, which was a thrilling one, through a strange country over ice-covered mountain roads, took the better part of a week. Much of the driving was done at night without lights, and the roads were often obliterated by their deep covering of snow.

The early days of January were days of busy preparation. By this time the first few cars of original equipment had begun to arrive, and night and day shifts, under the direction of Lieutenant Funkhouser, were organized to expedite the unloading. Details and trucks from Base Hospital 31 assisted in this work. The headquarters offices, which had been temporarily established in the Hotel Continental, moved into their permanent location on the second floor of the Moderne Annex, and the enlisted men's mess, which had been served jointly by Base Hospitals 31 and 32 in the Continental dining room, separated and operated independently. Messes for 32's men were established at the Cosmopolitain and Providence, and for the officers' and nurses in their respective quarters.

It was evident that the first task that faced the unit was to clean up the buildings and fit them for occupancy. Many of the hotels, especially those that had been occupied by the French, were turned over to the unit in an extremely unsanitary condition. There was a natural accumulation of refuse, floors were to be scrubbed, windows and woodwork washed-in fact a general housecleaning was necessary before furniture and equipment could be moved in. In addition to this there was a considerable amount of plumbing, electrical and carpenter work essential to fit the buildings for hospitals. The surgeries, laboratories and X-ray rooms required special lighting, and wiring for electrical apparatus. Sterilizing equipment was to be installed, and additional sinks and drains were required in some of the kitchens. Partitions had to be built and benches and tables constructed. The hospital was extremely fortunate in having among the enlisted personnel men who were ably qualified to accomplish this important work. Notable among these were McElwayne, Stuvel and Holloran in the plumbing; Gaither, Sertell and Iverson, carpentering; Drake and Cook, general electrical work, and Magee, whose installation of the X-ray equipment elicited praise from many X-ray technicians in both the American and French armies. The material required for all these important improvements was purchased under the direction of Lieutenant Bushey on motor trips to Nancy, Epinal and Neufchateau.

[Hitz, p. 50-52]

Continued –

By the middle of January all of the hospital buildings with the exception of the Royal, which was still in the process of leasing, had been cleaned, washed and scrubbed and the work of furnishing and equipping was well under way. Cars were unloaded and the contents hauled to the medical supply warehouse, where the crates and cases were unpacked and the contents distributed to the various buildings. Part of the equipment containing the additional 750 beds, together with their complement of mattresses, pillows, sheets and blankets, had arrived and was being installed in Hospitals B, C and E. These beds were a narrow, low French type, with metal slat springs, and compared unfavorably with the white enamel hospital beds of the original equipment, which were being set up in Hospital A. It might be mentioned here that Hospital A, with its original Red Cross equipment for 500 beds, became, when it was ready for service a few weeks later, one of the best and most perfectly equipped surgical hospitals in the A.E.F.

The first official inspection of Base Hospital 32 was made on January 17, 1918, when Colonels Stark and Reno and Lieutenant-Colonel Fife of the chief surgeon's office arrived in Contrexeville to inspect the progress the hospital was making in equipping and preparing the buildings for service. It was rumored at this time that the hospital might be pressed into service at an early date, and the rush of preparations was stimulated to an even greater degree. In order to take care of any emergency the staff was organized tentatively as follows:

Major H. R. Beery, Commanding Officer

Major E. D. Clark, Director

Major C. B. McCulloch, Adjutant

Captain Charles D. Humes, Registrar

Lieutenant F. P. Bushey, QuartermasterSurgical Service:

Major E. D. Clark, ChiefHospital A

Major C. B. McCulloch, Officer in Charge

Captain Lafayette Page, ear, nose and throat

Captain H. F. Byrnes, opthalmologist

Captain Eugene B. Mumford, orthopedist

Lieutenant R. C. Beeler, roentgenologist

Lieutenant J. W. Scherer, dentist

Lieutenant J. V. Sparks, dentist

Hospital B

Captain Alois B. Graham, Officer in ChargeMedical Service

Major Benays Kennedy, Chief

Hospital C

Lieutenant Joseph W. Ricketts, Officer in ChargeHospital D

Lieutenant Robert M. Moore, Officer in ChargeHospital E

Lieutenant Leslie H. Maxwell, Officer in Charge

The nursing personnel was also organized and tentative assignments made to the different sections.

[Hitz, p. 53-54]

Continued –

By the first of February, although the work of furnishing and equipping the buildings was far from complete, Base Hospital 32 was nevertheless in a condition for emergency service if the necessity arose. The unit at this time was deprived of the leadership of Major Beery, whose health failed under the strain of all this early work, and who was transferred to Hospital A, where it was hoped a complete rest might restore him to active duty. Subsequently Major Beery was relieved from duty with Base Hospital 32 and sent to Base Hospital No. 8, and from here he was transferred to the United States on March 1. During Major Beery's illness and after his transfer Major Clark acted as commanding officer, and it was under his leadership that the buildings were prepared and the unit organized for active duty.

The month of February was devoted to the final details of preparation. Additional supplies were requisitioned and received from the medical supply depots and from the Red Cross warehouse at Neufchateau. Authority was granted to take over any necessary items of equipment from the French Service de Sante, and numerous articles of hospital furniture, surgical and pharmaceutical supplies were acquired in this manner. Under the direction· of Sergeant Callis the hospital kitchens were equipped and organized. Negotiations were started by Lieutenant Bushey for the leasing of the power plant, which had heretofore been under municipal control. Telephones were installed by the United States Signal Corps and arrangements were made with the mayor of Contrexeville for the use of two small fire pumps of doubtful efficiency, a hundred feet or so of hose, and the few ladders which comprised the town's fire equipment.

[Hitz, p. 55-56]

Continued –

The end of February found the hospital ready for service. In the two months that elapsed since the hospital's arrival an almost incredible amount of work had been done. Dirty, unsanitary hotels had been transformed. into clean, shining hospitals. More than fifty carloads of supplies and equipment had been unloaded and installed. One thousand beds were standing, made up r.eady to receive patients. Kitchens, laboratories, pharmacies, surgeries, dressing rooms and the X-ray and special departments were equipped, organized and ready for service.

Contrexeville itself had changed in appearance. Streets had been cleaned, truckloads of accumulated refuse around the various buildings had been hauled away and the grounds had been thoroughly policed. In the world outside Contrexeville big things were happening. American troops were pouring into France in increasing numbers. Rumors of the impending spring offensive multiplied daily. On both sides of the lines divisions were shifted nervously from one place to another, and on every sector raids and minor actions foretold the mightier operations that were soon to follow.

[Hitz, p. 57]

March 1918 --

Up until this time a few patients from the personnel and an occasional allied patient had been admitted to the hospital, but no convoys of any size, either by train or ambulance, had been received. On March 19th a trainload of patients for the Vittel Center passed through Contrexeville, and on March 22nd a telegram to the commanding officer of Base Hospital 32 brought the information that a train was en route for Contrexeville which , was due to arrive the following day. On Saturday, March 23rd, at 5:00 p.m., American Hospital Train 52 arrived. It carried 336 American patients, of which all but twenty-six officers were received by Base Hospital 32. The officers, in accordance with previous arrangements, were turned over to Base Hospital 31.

[Hitz, p 71]

Formation of Unit R

(In the unit history of Base Hospital 32, editor Benjamin D. Hitz acknowledges Clarence R. Johnston for the history of Hospital Unit R, Hitz, pp. 58-67)

It has been previously noted that the capacity of Base Hospital 32 had been increased, shortly after their arrival at Contrexeville, from 500 to 1,250 beds. To take care of this expansion, additional equipment had been received and installed, but there had been no increase in the personnel.

Early in March information was received from the chief surgeon's office indicating that additional personnel --officers, nurses and enlisted men-would be assigned to the hospital at an early date, and on March 13th this information was confirmed by the arrival of Hospital Unit R.

Hospital Unit R, a southeastern Iowa organization which upon its arrival in France for active duty became a part of Base Hospital No. 32, traces its "ancestry" back to the day the United States declared war upon Germany. In Fairfield, Iowa, a busy little city of 7,500 persons, lived Dr. J. Fred Clarke. He had served in the Spanish-American War during the entire period of hostilities and while the occupation of Cuba was in progress. In the days of '98 he had been associated with Colonel Jefferson R. Kean, who on April 6, 1917, was in charge of military hospitalization work for the government. The declaration of war was adopted by the congress of the United States in time for all the evening papers of the country to carry the story on that day.

That night a telegram, signed by J. Fred Clarke went from Fairfield to Colonel Kean at Washington. It said, “What can I do to help our cause?” The next day the answer came, giving the fragmentary outline upon which hospital units were to be formed all over the country as a part of the great plan the medical department of the army stood ready to work out and put into operation. Dr. Clarke wasted no time. Within a few days he had consulted other doctors in his community, had talked the matter over with a few of the nurses he knew stood ready to "do their bit" and more, and had checked over a tentative list of enlisted men. Hospital Unit R was under way.

In every county seat in that section of Iowa new Red Cross chapters were springing up like the proverbial mushrooms over night and inactive organizations were instantly alive to the situation. They rallied, at once, to Dr. Clarke's organization and set about assisting it. Letters of inquiry began pouring into his office at Fairfield, asking what could be done to help him. In a little while, out of the chaotic confusion of the first few weeks, the plans began to take some sort of tangible form.

Dr. James Frederick Clarke, Fairfield, IA (photo from The Palimpsest, Vol. 67, No. 5, Iowa State Historical Society, Sept.-October 1986.)

The unit, recruited for service with the United States forces at home or abroad, was .to consist of twelve doctors, commissioned officers in the medical corps of the army, twenty-one nurses and fifty enlisted men. It was under the direction of the American Red Cross in the beginning, and remained so for several months. First enrollments were under Red Cross regulations.

While smaller in population than many of the other towns and cities of the ten or a dozen southeastern Iowa counties which fell into line behind the unit, Fairfield remained its home and its center. Here all the administrative work was handled by Dr. Clarke. Far into the night the director of the unit pored over his records, studied his applications, sifted and sorted, adjusted and checked, always in an effort to get the best. Red Cross chapters in all the towns in that section of the state went to work with a zest making supplies for the unit. Their women worked day and night, rolling miles and miles of bandages, cutting, stitching and packing hundreds of dozens of pairs of pajamas, bed socks, towels, caps, gowns, masks and other hospital equipment. Money poured into the treasuries and generous checks were sent, with a “do your best for our boys with it,” to Fairfield.

The purchase of equipment began, and as the summer wore on additional warehouse room had to be secured in Fairfield to hold the generous contributions of these people of southeastern Iowa. An X-ray machine came from Burlington, a truck from Mt. Pleasant, Ottumwa sent $10,000 in cash and box after box of supplies. Centerville, Oskaloosa, Keokuk, Washington, Bloomfield, all the centers of population in that section of the state were represented in the vast array of equipment with which the unit was furnished during the summer and early autumn. With the cash contributions which continued to pour into the Fairfield headquarters during this period, surgical instruments, operating tables, beds, cots, kitchen supplies, blankets and the thousand and one other things which go to equip a hospital we.re· ·purchased. Dr. Clarke supervised all this work. F. C. Morgan of Centerville, Iowa, was the purchasing agent for the unit, and Frank Ricksher, Fairfield banker, was the organization's bursar.

“But, when do we go?” began to be the cry around that part of the country.

Dr. Clarke, who was now Major Clarke of the Medical Reserve Corps, had chosen his fifty enlisted men, and they had been sworn into service as members of the Enlisted Medical Reserve Corps on August 8th, 9th and 10th. Miss Amy Beers, superintendent of the Jefferson County Hospital at Fairfield, which served as the parent organization for the unit, and who had been chosen as chief nurse, was a member of the Army Nurse Corps, and was getting her personnel lined up. Some of the women had already been called into active service in southern cantonments of the United States. Major Clarke had chosen his twelve officers and they had all received their commissions. There were six captains and five lieutenants. The organization had been officially designated by the War Department as Hospital Unit R, and was one of the two such units Iowa maintained during the war, the other being Hospital Unit K from Council Bluffs, with Colonel Donald MacCray in command.

Then followed a long period of waiting and restlessness and rumor. Every week carried a new story or a fresh version of an old one. The men began to seek transfers into other groups which seemed to have a better chance to “get across.” About December 1st came word that the unit probably would not be called out before spring. Everybody settled down for a “long, hard winter.” Then, like the much-prated bolt out of a clear sky, came the orders for Hospital Unit R to proceed to Fort McPherson, Georgia, for training and equipment preparatory for embarkation overseas.

That was on December 11, 1917. By noon the next day the men were on duty at the Fairfield Iowa National Guard armory, where they were quartered until December 15th. On that night at 9 o'clock the enlisted men and the officers left for Georgia, arriving three days later. The nurses were not called into service until the following month.

At Fort McPherson, on the outskirts of Atlanta, the Iowa boys found themselves to be a part of many such groups from all over the country. They were quartered in the same barracks and had a joint mess hall with Hospital Unit B, from Yonkers, N.Y. Across the street was Unit G, from Syracuse, and Unit H, from Fordham, New York City. Close by were Unit I, from Anderson, Ind.; Unit C, from Charlotte, N. C.; Unit W, from Springfield, Ill.; Units, from Spokane, Wash., and Base Hospital No. 26, from the famous Mayo establishment at Rochester, Minn., and so on they went up and down every street in that section of the reserve.

Long, cloudless days were spent on the McPherson drill fields and parade grounds. Still longer nights were spent in the rickety wooden barracks trying to keep warm under a couple of cotton blankets, while the wind whistled through the pine trees.

The boys thought they knew Dame Rumor pretty well before they left Iowa, but they soon found out that they had only a mere passing acquaintance with the lady. They never knew her until they reached Georgia. Six times, from January 1st until February 4th, they were leaving. Once they had the equipment loaded on the train, and twice it was on the trucks on the way to the station. On February 4th, at noon, the unit did pull out for Camp Merritt, New Jersey.

A few changes in the personnel took place at Fort McPherson. Captain John R. Walker, of Fort Madison, Iowa, who was the unit's adjutant, was disqualified for overseas service. He later became camp surgeon at Camp Pike, Arkansas. His place was taken on the unit roster by his brother, Captain Ben S. Walker of Corydon, Iowa, who was in training at Fort Riley, Kan., when called to Atlanta. Henry F. McCullough of Chariton, Iowa, an enlisted man, had applied for a transfer to the air service before the unit was called into active service and received his orders to proceed to Rantoul, Ill., soon after the organization reached Georgia. His place was taken by Joseph A. Duffy, who came to Atlanta from Kansas City.

While the officers and enlisted men were preparing to leave Fort McPherson, the nurses had been called from their homes in various parts of Iowa and from the southern camps where they were in service to Governor's Island, New York. There they were trained and equipped and joined the remainder of the unit in New York.

Arriving at Camp Merritt on the morning of February 7th, the stay there was devoted to the final stages of equipment for overseas service and short drills and hikes. On the morning of Saturday, February 16, 1918, the officers and men marched out of Camp Merritt, through a heavy snow, at 3 :30 a. m., and boarded a train at Tenafly, N.J., for New York. On the Cunard docks in that city they were joined by the nurses, and all went aboard H.M.S. Carmania. At 4 o'clock that afternoon, in a hard, driving rain, the big gray liner stole out to Ambrose Channel Lightship, where she lay until midnight, then turned her nose north, and Hospital Unit R was off on the great adventure.

The next morning, Sunday, with a brilliant blue sky and a reflecting ocean like a mill pond, they were heading up the east coast of the United States for Halifax. Arriving there the next day, the ship anchored a mile out in the inner basin. Although it was twelve to fifteen degrees below zero all the time, the Iowans used to stand for many minutes on deck at night to see the beautiful harbor, bathed in a full moon's light and touched by the glow of the ever-marvelous northern rays.

On Thursday, February 21st, early in the morning, unusual activity was noticed. Before noon, two, four, six and then seven boats, some battleship gray like the Carmania, others zebra-coated in their many colors of camouflage, poked their bows around the bluff and slid in alongside the Carmania. The stage seemed set. Everybody was on his toes. But there seemed to be a feeling of waiting; for the chief actor, perhaps. Then he appeared-a sleek, swift, sure-looking cruiser with the silky folds of Old Glory flapping in the sunlight from the stern. Three in a row, and three across, the ships took their places.

With the Stars and Stripes as their guide, the convoy moved. Just as the hills of Halifax were taking their last dip in the winter afternoon's dusk glow the troop-laden ships passed the outpost cliffs and went out to sea.

Then followed fifteen days of smooth seas and seas that were not so smooth. Lifeboat drills became as common as marmalade and tea for breakfast. Standing at attention for sixty-five minutes because “somebody” forgot you were there meant nothing at all in the lives of these young Iowans “sailing the ocean blue” in the face of sleet and snow and wind and possibly submarines.

Old Lady Rumor worked overtime on her job all the way over, but finally, with nothing more exciting than a cable breaking loose on the last night in the danger zone and making every one certain that the boat had been hit by a torpedo, the good ship Carmania tied up at the Liverpool docks at 2 a. m., on March 4th. Disembarkation began at 9 o'clock and was finished in time for Captain Herrick and the nurses to get away to France, with only a glimpse of England, and the remainder of the officers and the men to pile on to the funny little English toy cars and take a seven-hour jog to Southampton town. It rained all the way down from Liverpool. With only a brief stop at Sheffield for coffee the outfit arrived at Southampton at I o'clock in the morning. Right alongside the tracks lay a big boat. Everybody said, “We are going right across to France to-night.”

But they were all wrong. There was a Canadian officer, who had evidently slept all day in preparation for the event, standing right there to guide these "travelers" to their next stop. Right up through the business section of Southampton the trainload of troops was marched at a cadence which is estimated to be anything from 100 to 500. Out into the residence district, past parks and lanes and drives, they stumbled over the cobblestones without a single stop to rest. The crowd began to decide they were marching back to Liverpool, because somebody had forgotten his umbrella, or his ice cream bucket, or some similar army necessity. Finally, after a few hours and a few more miles, the column halted at the Southampton Commons at 4 a.m.

Eight in a tent, plenty of blankets on the floor, but the sweetest words in a long time when the Tommy bellowed, “Now, you'se don't need to get hup huntil ten in the mawnun.” And then, with the day, it was like stepping into another world. Leaving Camp Merritt wading through a heavy snow, facing sleet and wind and subzero weather all the way across the ocean and then this -- perfect spring skies, daffodils nodding their yellow bonnets all along the roadsides, primroses in the window boxes of the little, hedged-in, brick homes, holly bushes with their sparkling berries everywhere, lakes, winding paths. It was a real rest camp.

Five days were spent there, and then on Saturday, March 9th, at noon, the unit marched down to the docks. The boat was ready this time, and at 4 o'clock that afternoon the trip across the channel began. At dusk everybody was ordered below and down they piled. Rank was lost in the shuffle. Bucks sat on majors' necks, and sergeants paid colonels no mind at all. No one could move more than three inches to either side, up or down. With this conglomerate mess of men and baggage hiding somewhere down in the inside, the ship stopped in the middle of the channel to fix a broken steam pipe. The convoying destroyer had to scamper back to see another boat over, so the disabled sister was left alone, riding at anchor, with a full moon pointing her out to any marauder who might have been swinging his periscope that way. Luck was with the crowd, though, and after a while the pipe was mended and the old boat hobbled along on its way.

The dawn of Sunday, March 10th, brought the Iowans their first glimpse of France-the harbor of Le Havre. The unit reached a rest camp, nestled in the rock piles of outer Havre, about 10 a.m., where preparations were made to stay for several days. At 2 o'clock, the next morning, however, it was “Everybody out,” and at 4 o'clock the crowd was back down in 'Havre climbing aboard a French passenger train, made up of “1 1 1 's,” which never had any intention of starting before 9 o'clock that morning, and which did not finally make up its mind to go until noon. It was a beautiful ride down through northwestern France that early spring afternoon. The valley of the Marne was reached before dark. The day closed with a wonderful sunset gilding the white crosses scattered over the fields.

That night, near the hour of twelve, some German planes were flying back to their lines from Paris, where they had brought terror and destruction and death. To the north, near the suburb of Nieully, one keen-eyed Hun spied a train standing at the entrance switch to the station yards. He gauged his distance, and threw his bomb. His companions did the same. They missed the train, but 300 yards ahead they smashed the station, killed several persons, and injured many others. The tracks were torn and twisted. Less than 200 yards to the rear of the train a great hole, fifty feet across and twenty feet deep, was torn in the earth. Windows were broken in the train, and sides of the cars splintered. On that train rode Hospital Unit R and Units G, H and B.

With that baptism of fire the occupants of the coaches were ready for almost anything, but the tracks were repaired and the train moved on early in the morning.

Another day and night across the checkered fields of France rapidly putting on their spring dress, and then a turn north toward the cedar-covered hills of the Vosges.

At noon on Wednesday, March 13, 1918, the officers and men of Hospital Unit R piled off the train at Contrexeville. They were met by the nurses, who had arrived several days previous. That afternoon the commanding officer reported, turning his organization over to Base Hospital No. 32, and from that time on the Iowans were affiliated with the Indiana unit.

[Hitz,p. 58-67]