First Impressions

“Contrexeville,” by M. E. Kaletzki in Kaletzki, Charles Hirsch. Official history USA Base Hospital No. 31 of Youngstown, Ohio: And Unit G of Syracuse University. Syracuse, NY, Craftsman Press, 1919, pp. 117-120.

Rattling, coasting, jerking a bit forward and four or five bits backward the long ramshackle collection of rolling stock known as a “train militaire” finally climbed the grade through the long woods of ancient oak leading from Martigny-les-Bains out into a stretch of open country bound by wind-swept and partly wooded hills. From the boys who had ridden half way across France on the tops of the cars, and who were still on top, we heard a great cry. It was such a sound as might have thrilled the soul of Columbus when the first of his polyglot crew cried “Land ahoy” in whatever language it was they used.

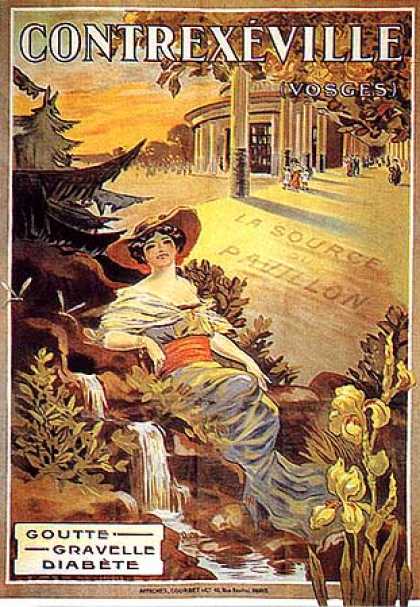

Poster promoting Contrexeville's Source du Pavillon

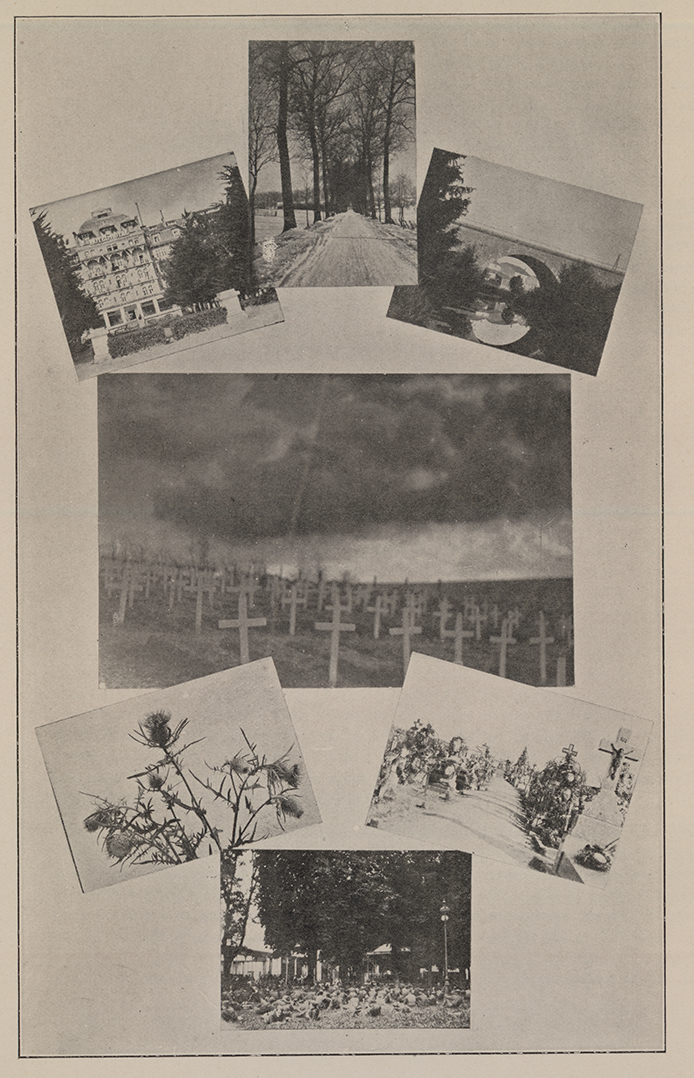

It was the Hotel Cosmopolitain that occasioned the outburst. Save for it we would not have known for another fifteen minutes that we had finally arrived in Contrexeville. But this great structure of stucco and brick was erected on the summit of one of the hills that enring Contrexeville. No matter from what direction the traveller approaches the village of our labors the first and only building he sees is the “Cosmo.” All the rest of the village, with its dozens of hotels and hundreds of houses, is stowed away neatly into a pocket of the Vosges foothills. There was not a day until the armistice was signed that we did not look up at the giant “Cosmo” and say: “What a mark for a Boche bomb.”

From the appearance of the railroad station Contrexeville was only a little better than the scores of villages through which the train had passed. The same covered waiting stalls on both sides of the track, the same automatic gong with its harassing clang and the same passenger station with its red wooden picket fence, its two water towers and the inevitable outhouses well screened by clipped hedges. Leading into the village proper from the station was a well kept road lined with pollard willows, on one side of the street small gardens, broken only by the ever present cafes, on the other side some really handsome villas – the first evidence that this was not, in truth, like all other villages in France. At the first intersection one finds the first of the hotels, three large structures whose outward appearance of solidity and dimension belied the inconsistencies of design and antiquities of construction with which their interiors abounded. The Royal, the newest of the hotels, looked as though it might have been designed by an architect in Pasadena, or Los Angeles, or perhaps San Antonio. It was more Spanish than French. But the Paris and the Providence were all French, from the stone stairs to the mansard roofs. Turning into the first street to the right, one passes the first typically French street of the town, narrow and steep and lined with buildings that would fit in any village in France. A few steps further down and the main thoroughfare of the village is in view, but before it is reached you see the high grilled iron fence, the symmetrical garden plots and the long Graeco-Byzantine colonnade of the “Etablissment des Eaux.”

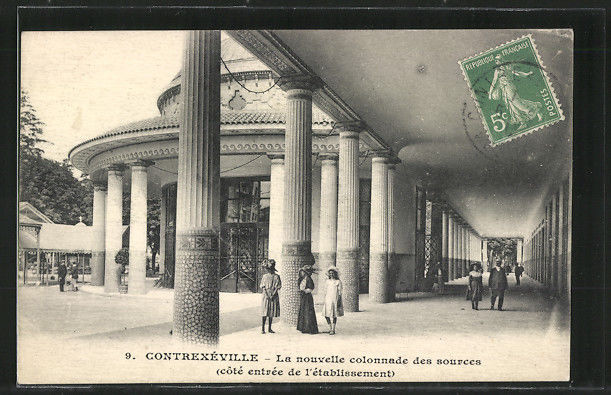

Postcard of the Colonnade at Contrexeville (image captured from eBay)

But the main thoroughfare first. Once upon a time the River Vair (in France it is a river – in America it would be a brook) traversed the main street of the village, and it was also the principal artery in the village sewer system. Thousands of visitors who came from all parts of France to benefit by the waters were offended by the sight and smell of the stream. In response to their protests the stream was covered with a structure of reinforced concrete approximately level with the roadway which ran on either side of the stream. The first fifty yards of it were planted with buckeye [chestnut] trees, and the net result was called the esplanade.

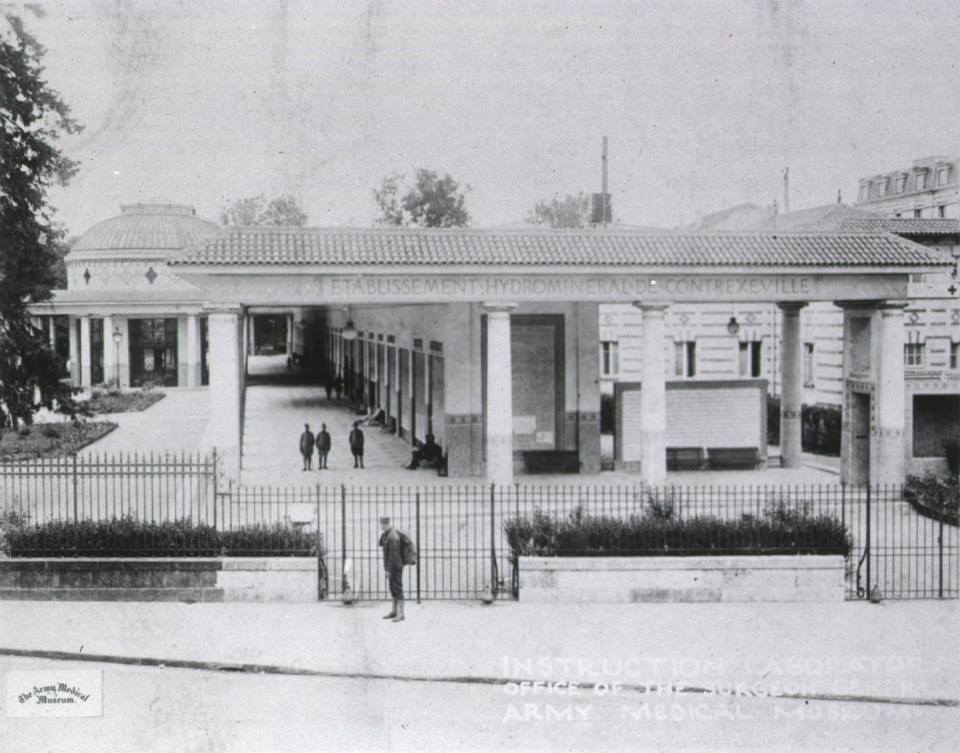

L'Etablissement Hydromineral de Contrexeville (image from the Youngstown State University Special Collections archive)

Most important among the structures in the village is the bath-house. The colonnade defines one side of it. For beauty of design, thoroughness of equipment and facility of operation it probably is without a peer in France – or America either. Here in the days before the war came nobles and commoners – prosperous commoners to be sure. A Russian Grand Duchess had a bath all her own and the Shah of Persia had for his own use a room with luxuries as the Orient never knew – a rectangular bath tub of tile and marble sunk into the floor of the same material, a shower bath of complex design and facilities for about every other kind of bath known. The bath-house itself is a circular building, with circular corridors into which the bathrooms opened. In the center were the massage, X-Ray and other special bath rooms. Through the initiative and generosity of the American Red Cross this entire establishment with all its facilities were placed at the disposal of the American Expeditionary Forces, under the joint direction of Base Hospitals 31 and 32. More than 50,000 baths were given to personnel and patients.

The colonnade itself, a gem of architectural design, was built as a tangent to the circular bathhouse. Opening into the colonnade was another circular structure, a huge dome affair which housed only the principal of the Contrexeville springs, the Source du Pavilion. During the summer months large rattan chairs were arranged around the circular walls and in the early morning hours the “buveurs” [drinkers] would sit and talk of this and that, and at regular intervals would go to the spring and drink a very exact amount of water from a graduate glass. A covered passageway led to the Hotel de l'Etablissement, a huge structure built at intervals covering more than half a century. The villagers used to say that one kick from a good horse would send the entire structure tumbling into a heap. Because of the many additions and alterations which had been made one required the services of a guide in exploring the building. But in time of emergency, when almost every day saw a new trainload of wounded, when every available bed was needed, the old “Establishment,” as we called it, served a mighty useful purpose. At the close of our stay in France it served as a barracks for all the enlisted men-probably the most luxurious barracks in France.

Continuing along the covered passageway one came to the Casino, a handsome building of white stone and glass, with a vast glass-enclosed veranda. Within the Casino were a theater, highly decorated game rooms and a foyer of marble and mirror, leading to the theater. The veranda, with a glossy floor of marble tile was used for a few dances in the early summer months, but when the patients began to roll in by the hundreds, more than two hundred beds were set up and maintained there. Hundreds of men with lesser wounds spent their entire period in the base hospital out on the Casino porch-probably the largest single ward in the A.E.F. The gaming rooms were wards, too. What had been the baccara room, where in other times, men and women lost and gained fortunes, was converted into the “shock ward” where the most serious cases were taken after operation. The operating room itself was in the old foyer of the theater-a highly practicable place, with an abundance of light.

The Casino, the Hotel de l'Etablissement and the colonnade, together with the Hotel de Ia Souveraine, the smallest but most luxurious of the Contrexeville hotels, opened into the park – a small paradise, with reaches of gently sloping lawn, curving driveways, well grouped trees and carefully groomed hedges. One can only imagine what a great source of rest and comfort this park was to be to thousands of convalescent sick and wounded. The Continental and Harmand hotels, occupied by Base 31, the Hotel of the Twelve Apostles, used as the nurses' home, and the Hotel DuParc, which housed most of the officers, faced onto the street which bordered one side of the park. Except for a few clustered buildings this street looked much like an American street. But leading from it up a steep grade, guarded by an iron railing was another street, vivid in contrast. It had the tiny white houses with red tile roofs, the arched barn doorways, the small iron balconies of high design and low utility, an enigmatic structure with a collection of bells on the roof-and in front of each house a little bench on which no one ever seemed to sit. Facing the esplanade were the hotels Martin Aine, Martin Felix and Thiery, all of which were used by Base 31, the last named, as a hospital for officers only.

Little Contrexeville nestling in the hills, with only its garish “Cosmo” and the power-house smoke stack extending above the traveler's line of vision, with its strange collection of natives, representing all extremes from the most carefully cultured and tutored to the most lowly and boorish peasants, and with its cluster of ancient hotels, is a landmark, a shrine of remembrance, not only for the thousands of patients who came there and were sent on their way to duty or to a long convalescence at home, but as well to those who were the spirit and moving force of the hospital. Forever it must remain as a sacred spot to the relatives of those who passed the Great Divide while at Contrexeville. High on the hill back of the ancient Catholic church, back of the native cemetery with its too highly ornate memorials, is the little plot of ground where there are wooden crosses, row on row-and floating over all the Stars and Stripes in whose name they fought and died.

Postcard of Avenue de la Gare, Contrexeville (image captured from eBay)

A page from the unit history of Base Hospital 31 with images of Contrexeville. Top, from left to right: Hotel Royal at Labaule (where nurses waited for transport back to the U.S.); winter scene on road to Dombrot; bridge on road to Outrancourt. Center: American cemetery in Contrexeville. Bottom, from left to right: Lorraine thistle; convalescents at a concert in the park at Contrexeville; a path through the French cemetery at Contrexeville.