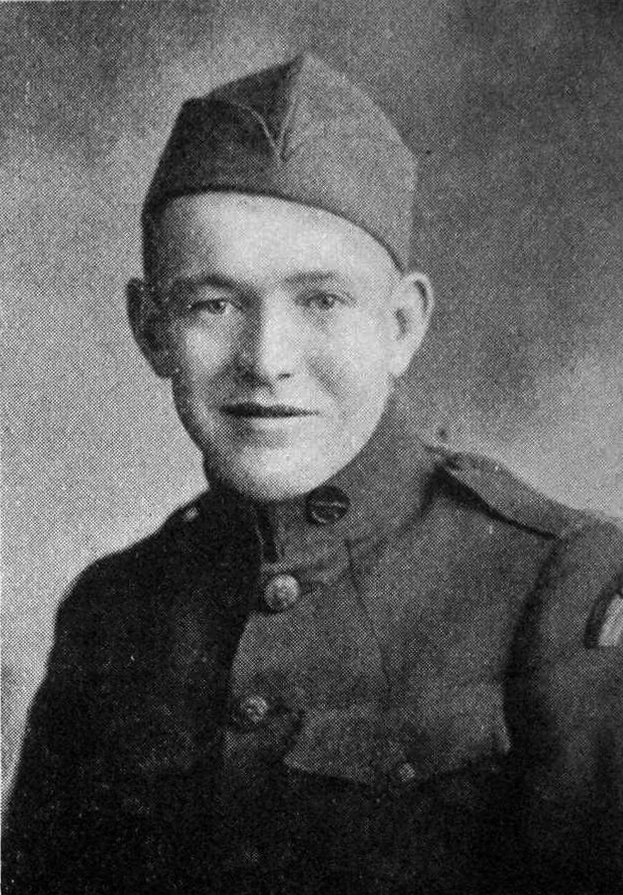

Harry Swift

Harry Swift was my mother’s second cousin. He was born in Washington, IA, on 26 September 1896, the son of Francis Swift and Nellie Boyd. His grandparents, Martin Swift and Mary Gavin, were immigrants from Ireland.

Pvt. Harry Swift

He enlisted in service on May 25, 1917, shortly after the U.S. declared war on Germany, and was initially assigned to Company K of the First Iowa Infantry. In July, President Wilson issued an order to call the National Guard units into federal service, and many men from Iowa’s First and Second Infantry regiments were transferred to the Third Infantry Regiment, which was renamed the 168th Infantry Regiment. The regiment mobilized at the State Fairgrounds in Des Moines and joined the 42nd Division – the Rainbow Division. They departed Iowa in September 1917 for Camp Mills, NY, where other regiments were assembling for embarkation.

The 42nd Division was created from units in 26 states and the District of Columbia. It was composed of the 83rd Infantry Brigade (165th and 166th Infantry Regiments) and the 84th Infantry Brigade (167th and 168th Infantry Regiments), together with supporting units such as artillery, engineers, signals and so on. The division was shipped overseas in October 1917, one of the first divisions of the American Expeditionary Force to arrive in France.

The division initially departed Camp Mills on 18 October 1917 on board the SS President Grant, originally a German vessel which has been seized by the US and appropriated for service. They joined a convoy of seven other ships, transporting a total of 17,000 men. In was an inauspicious start. The Grant proved unseaworthy when, 5 days into the voyage the ship’s boilers gave out, and the ship had to return to Camp Mills. To make matters worse, measles had broken out on board and several men were sick. Things were miserable for a few days when the 168th waited for transport, at one point without rations because their kitchens were still on board the ship. John H. Taber’s The Story of the 168th Infantry tells how this was resolved:

It was then that we found out what friends we had in Alabama (the 167th Infantry.) They had only enough rations for themselves – but Iowa was next door and hungry. An invitation was immediately rushed over for each company in the 168th to report to the corresponding letter company in the 167th for breakfast. All Sunday, the Alabama regiment fed us, and planned to furnish our meals until the arrival of our stoves and kitchen equipment, which, fortunately for them, came late that night.

The 168th departed Camp Mills a second time on 14 November 1917, this time on the SS Celtic, and the SS Aurania. Seventeen days later, they landed in Liverpool. One week later, in December 1917, they were at Le Havre.

Upon their arrival, the 42nd Division began intensive training with the British and French armies in learning the basics of trench warfare. In 1918, the division took part in four major operations: the Champagne-Marne, the Aisne-Marne, the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. In total, it saw 264 days of combat.

The division moved from Le Harve to the Lorraine region for side-by-side training with French troops. Though some of the journey was done in drafty railroad cars, much of it was completed in several hard days of marching in bitter cold winter weather. On the day after Christmas, 1917, on orders from Col. Douglas MacArthur, the division undertook a 3-day march from Saint-Blin to Rolampont in subfreezing temperatures. Not all the troops took the same route -- for some it was a 36-mile march, for others it was up to 118 miles. Laden with heavy packs and marching through snow that was ankle- to knee-deep, some of the men lacked overcoats and gloves. Nimod Fraser writes, in his book (Send the Alabamians), "Later, men identified it as the beginning of the division's reputation for reliability and toughness. The 42nd Division had not yet seen combat, and this experience brought the men and units closer together than anything they had previously endured."

But the results were predictable - while the commanders may have viewed the march as one to toughen up the raw troops, a nurse's point of view is quite different. Here is what Maude Essig wrote in her journal on Dec. 30, 1917 (she was on temporary assignment at Chaumont's Base Hospital 15 when the casualties from the march began to arrive at that hospital):

"The present rush of work is due to a tragic hike, ordered by some commanding officer, for members of 42nd Div., across France, boys were unduly exposed to freezing weather, pneumonia, frozen feet, bad ears (mastoiditis), meningitis etc., not to mention the very common cold. Most of the patients came during the past week. Four bldgs. have already been taken over from the French to meet the disaster, bad situation and we were called upon to help alleviate the suffering."

From then until early February, things were bitterly hard for the men of the 42nd Division. It was miserable for all of them -- particularly the men from Alabama who were not well conditioned to winter weather. Among the 168th Infantry (the Iowa regiment), the lack of adequate winter clothing, drafty billets in barns with no heat, and outbreaks of disease (mumps, measles, pneumonia, meningitis, scarlet fever) contributed to the deaths of 10 men.

In all, twenty-two men from Harry Swift's regiment, the 168th Infantry, died before the unit was engaged in battle. (This does not include Henry Booth, a Keota man who left with 29 others to enlist at Camp Dodge. He became ill from a typhoid vaccination, developed pneumonia and died on May 17, 1918, before he could be accepted for military service.) When we remember that antibiotics were unknown to medicine at the time, it underscores the risks men and women took to serve in WW 1. Even what today might be considered a relatively minor infection could result in death in 1917-1919.

Their names, hometowns, and the dates and causes of death of those men in the 168th who died before reaching the battleground are as follows:

- Pvt. Charles Pritchard, Van Meter, IA – 9/6/1917 - auto accident near Des Moines

- Pvt. Clyde Barber, Council Bluffs, IA – 10/2/1917 - spinal meningitis

- Pvt. Thomas Arklese, Albia, IA – 10/20/1917 – acute peritonitis

Pvt. William C. N. Johnson, Prescott, IA – 11/19/1917 – measles and pneumonia (on voyage to France) - Pvt. James Mattingly, Ames, IA – 11/19/1917 – illness (unspecified)

- Pvt. Earl Coons, Prescott, IA – 12/1/1917 – illness (unspecified) one hour before the ship landed on the English coast

- Pvt. Ralph M. Miller, Orient, IA – 12/13/1917 – scarlet fever

- Pvt. George E. Truax, Des Moines, IA – 12/23/1917 – scarlet fever and pneumonia

- Pvt. St. Clair Willcox, Winterset, IA – 12/23/1917 – illness (unspecified)

- Pvt. Herbert Schroeder, Dubuque, IA – 12/25/1917 – pneumonia

Pvt. Herman A. Roose, Odebolt, IA – 12/31/1917 – pneumonia - Pvt. Norbert Wilson, Elliot, IA – 1/5/1918 – scarlet fever

- 2nd Lt. Scott McCormick New York City – 1/17/1918 – accident at Gondrecourt when sack of hand grenades he was carrying exploded

- Pvt. John W. Wasmer, Le Mars, IA – 1/20/1918 – illness (unspecified)

- Pvt. Adolph Fortsch, Fairbanks, IA – 2/1/1918 – illness (unspecified)

- Pvt. George R. Bullard, Ft. Dodge, IA – 2/15/1918 – cause not known (but he was sent to the hospital shortly after the unit arrived in France)

- Pvt. Andrew M. Reymer, McKeesport, PA – 2/17/1918 – fell under a rail car while trying to board a moving troop train

- Pvt. Edward Worth, Lorimor, IA – 3/1/1918 – blood poisoning from untreated ear abscess

- Sgt. Harry L. Calhoun, Allendale, MO – 3/23/1918 – injuries from an accident while loading the ship in Hoboken

- Pvt. Bert L. Smith, Elk Point, SD – 3/30/1918 – illness (unspecified)

- Pvt. Harlan F. Parker, Creston, IA – 1/1/1918 – pneumonia

- Pvt. Lewis Mayland, Des Moines, IA – 3/4/1918 – illness (unspecified)

Even on their way to battle in July 1918, the men from Iowa who marched with the 168th were able to appreciate the beauty of the Champagne region landscape. On July 23, 1918 – near Châlons and Coolus (south of Reims), Lt. John H. Taber of K Company (Harry Swift's company) remarked in his journal: “Have passed through a rich agricultural district, which has evoked favorable comments from our many farmer representatives.”

.jpg)

Fields near Èpieds, France

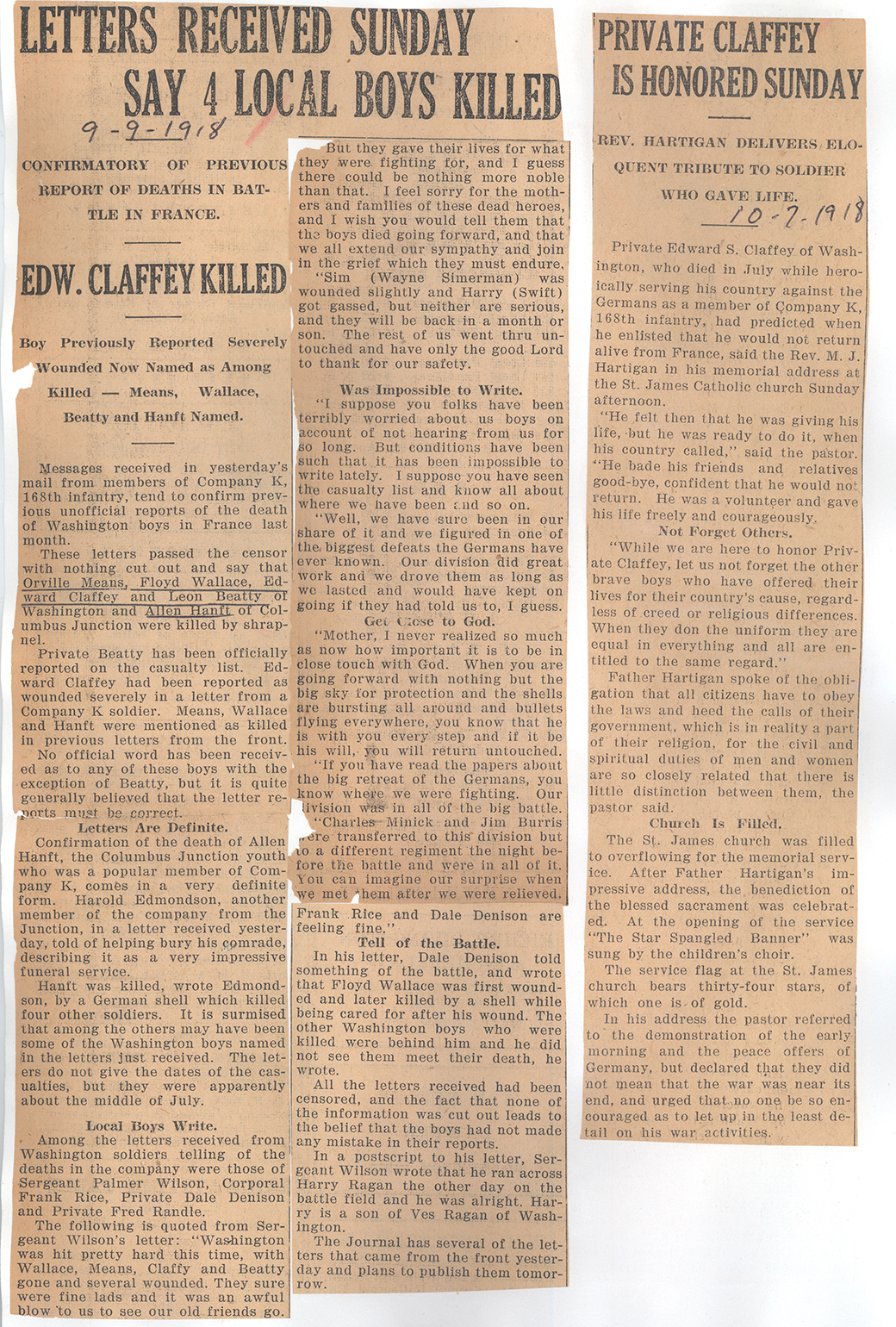

Washington, IA, suffered great losses at Château-Thierry, but their first battlefield loss came further north in the Champagne sector. But word did not reach Washington until late August and September. From a 1928 issue of the Washington Evening Journal, Helen Livingston recalls how Washington received word of the first battle casualties from Harry Swift's unit, the 168th Infantry. They had fought a terrible battle at in the Champagne sector, near Suippes, on July 15:

"Most of us remember it – it was on a Sunday morning during Chautauqua when a number of letters from boys 'Over There' referring to the death of a Washington boy reached Washington homes. In each case the boy was named but the name had been deleted by the censor and it was not until two days later, when official word reached the home of his parents, that we knew that Leon Beatty, son of Mr. and Mrs. S. P. Beatty, was the first Washington County boy to give up his life with the American Army in the World War."

- Helen Livingston, 1928 Wash. Ev. Journal, reprinted in the 16 July 1938 issue.

As they headed into battle near Château-Thierry, Lt. Taber’s journal records an incident which tells of the bravado of the Iowa men:

Orders to proceed to a position in the forest came from Brigade Headquarters which, along with the first aid station that was already caring for patients, had been established in the village. As the column started out it came upon a battery of French 75's, also preparing to go into action. "Are you going forward this morning?", an English-speaking artilleryman asked an Iowa doughboy.

"Yes", came the reply, "and if you'll just pick up your little ol' soixante-quinze and hitch on, we'll try to get you to Berlin before night."

"But surely you don't expect to get that far?" returned the serious-minded poilu.

A bit reluctantly, the American conceded:

"Well, there is some talk of stopping at the Rhine, but I dunno, I dunno about that. These fellers are Hell when they get started.''

On July 25-26, 1918, the Iowans engaged in the Battle of Croix Rouge Farm, where they suffered heavy losses. For a detailed description of the battle, see Nimrod Fraser’s book Send the Alabamians (or go to http://croixrougefarm.org/history-battle/). See also p. 90ff in John H. Taber’s journal, A Rainbow Division Lieutenant in France for a description of the actions of K Company of the 168th (Harry’s company.)

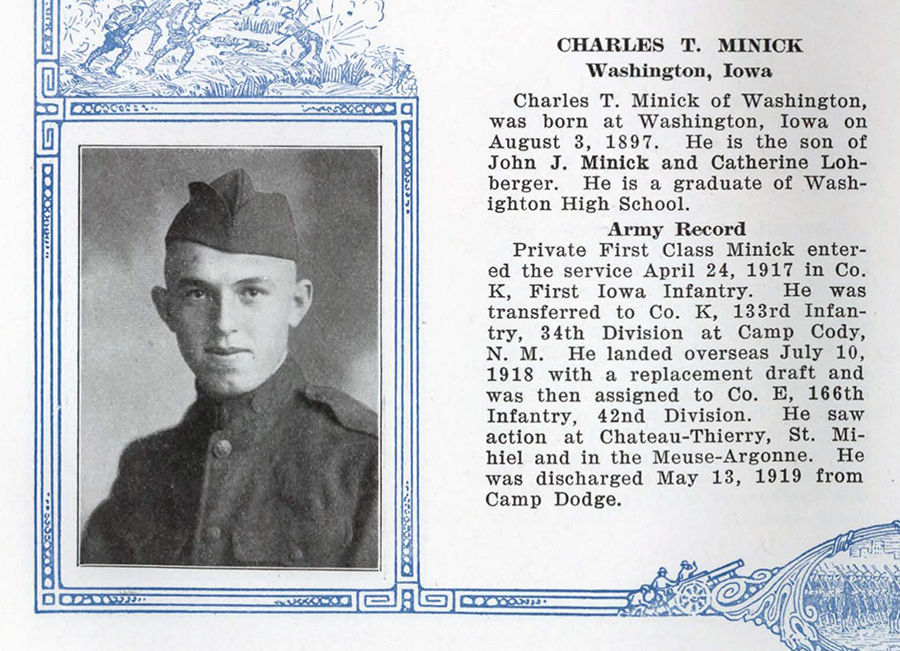

July 27, 1918 -- the day Harry Swift was injured -- was an awful day for the men from Washington County, IA. They were fighting with Company K of the 168th Infantry. The company was moving from the Fôret de Fère, near the Croix Rouge farm toward a German line on the north side of the Ourcq River. Having occupied the higher ground for weeks, the German artillery was extremely precise in their targeting, and Harry's platoon caught the brunt of the shellfire. Dewey McAvoy, Edward Claffey, Floyd Wallace, Homer Hawkins, Orville Means and John Flannigan -- all Washington, IA, men -- and Allen Hanft, from Columbus Junction were all hit (mostly with high explosive shells, though Flannigan was hit with machine gun fire), and all died. Wayne Simerman, Harry Swift, Glen Schuster and others were wounded. (Harry was injured by exposure to gas shells, which the Germans fired as the U.S. troops retreated on the 27th to fall back into the woods and dig in.) Despite losing nearly half of their number, the 168th pushed on to cross the Ourcq and the German troops fell back.

.jpg)

On D809, leading east toward Cierges (small cluster of buildings in the distance.) The 168th crossed open country like this as they pushed the Germans back across the Ourcq River.

Washington, IA, newspaper clippings from September and October 1918

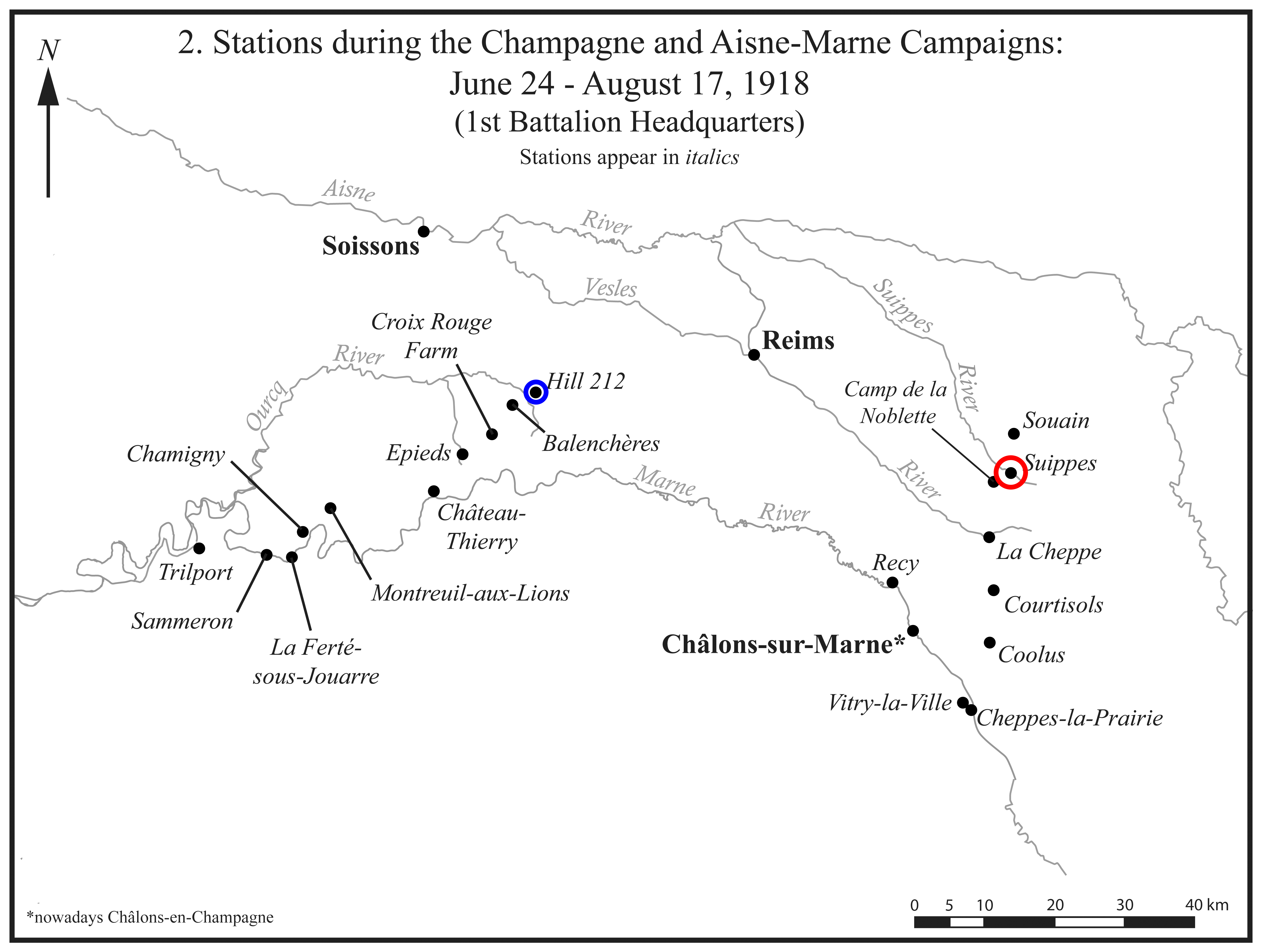

The map shown here shows the location of the July 27-28 engagement, indicated by the blue circle. Hill 212 was the higher ground above the Ourcq River, from which the German artillery rained down on the 42nd Division troops in the woods around Croix Rouge Farm. The red circle, at Suippes, shows the location of the battle in the Champagne sector where Leon Beatty of Washington, IA, was killed on July 15.

Stations in the Champagne and Aisne battles (map from Send the Alabamians)

Harry recovered (seemingly) from his injury and returned to his unit before the Armistice and was with them in Germany during the Occupation. In April 1919, he and the remnants of the 168th (1,200 of their original 3,075 men) boarded the SS Leviathan and headed home, arriving in New York on 25 April 1919. The unit stayed for a couple of weeks at Camp Upton and then, traveling on three trains, returned to Iowa.

However, the injuries from battle at Château-Thierry took their toll on Harry’s heart. Fourteen years after he returned home, when Harry was uptown in Washington, IA, on 23 Dec. 1933, he said he didn't feel well and was going to return to his car. But he dropped dead before he got there. His funeral was held the day after Christmas.

Clipping from the 28 Dec 1933 issue of the Washington Democrat Independent

The men who served as his pallbearers were all -- with the exception of one -- soldiers who served with him at Château-Thierry. The exception was Clayton A. Neiswanger. He was a veteran of the Spanish-American War and the Philippine campaign. He witnessed the surrender of Spanish troops in Cuba in 1898 and shortly thereafter fell seriously ill with malaria, which he battled for months but finally recovered. When Washington, IA, formed their VFW post in 1933, Clayton Neiswanger was a founding member and served as their first commander.

Of the 52 men from Washington County who served in the 168th (according to the book Washington Co in the World War), 17 men were wounded and 8 were killed:

From Washington (11 wounded, 7 killed):

- 1. Everett Griffith, HQ Company

- 2. Mark Dale Atkinson, K Co.

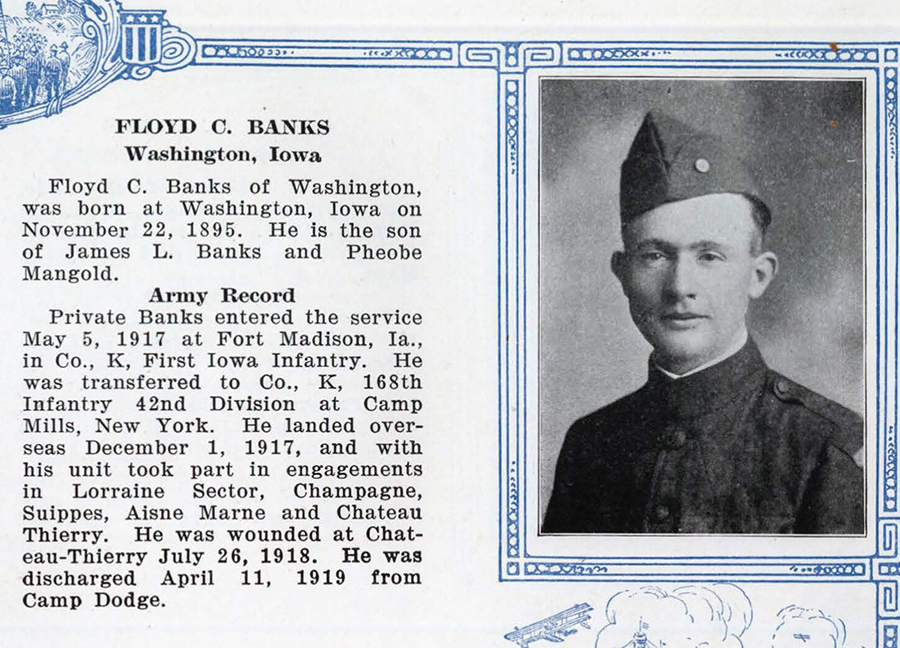

- 3. Floyd C. Banks, K Co. (wounded 26 July 1918)

- 4. Leon Beatty, K Co. (killed 15 July 1918 at Champagne)

- 5. Clair Beatty, K Co.

- 6. Benjamin D. Cherry, K Co. (wounded 27 July 1918)

- 7. Edward Claffey, K Co. (killed 27 July 1918)

- 8. Arthur K. Dankwardt, K Co. (arrived overseas 24 Oct 1918)

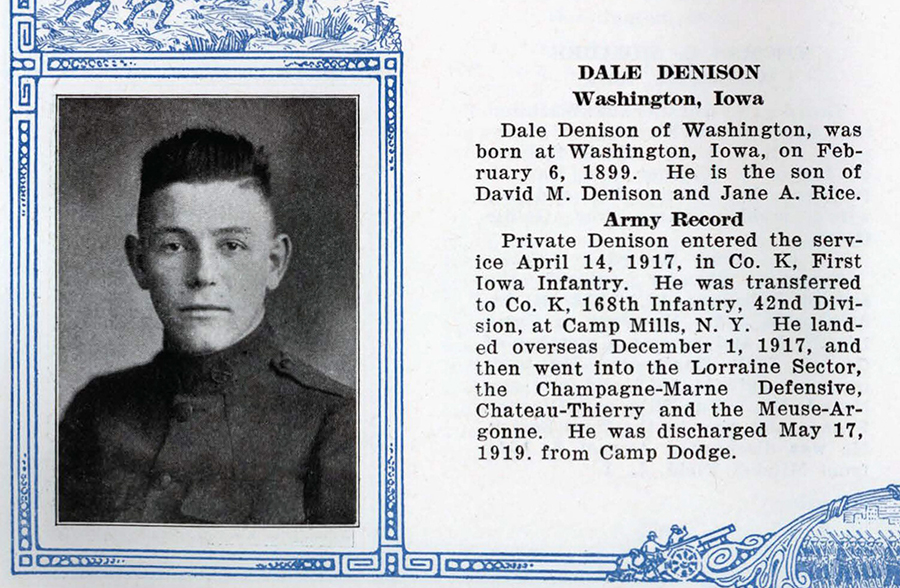

- 9. Dale Denison, K Co.

- 10. John Flannigan, K Co., died from machine gun wounds received on 28 July 1918 on the advance to the Ourcq River. Died in hospital later on.

- 11. Victor C. Freding , K Co.

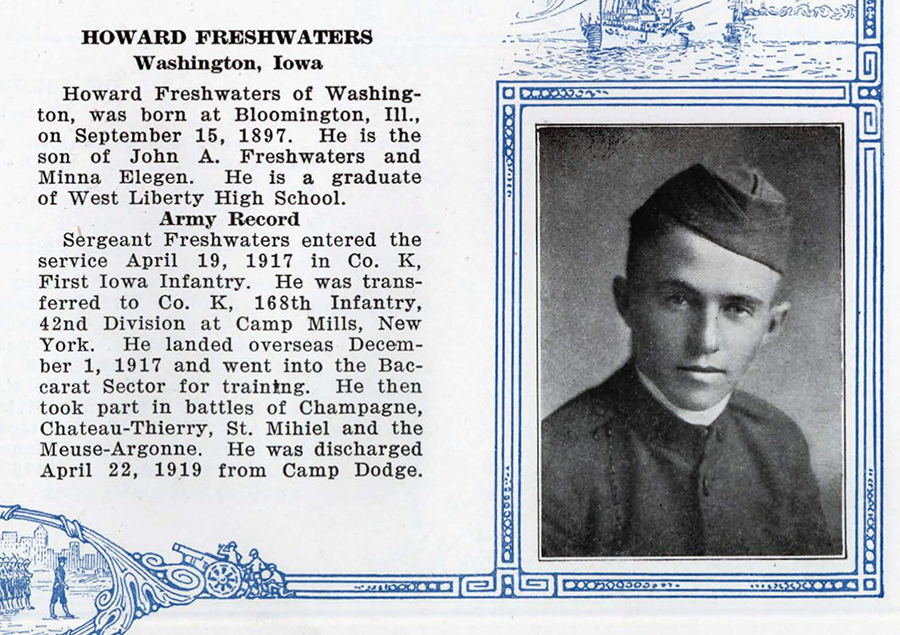

- 12. Howard Freshwater, K Co.

- 13. William E. Fulton, K Co.

- 14. Edgar A. Hays, K Co. (arrived overseas 24 Oct 1918)

- 15. Ray B. Kurtz, K Co.

- 16. David Palmer Livingston, K Co. (gassed 2 Aug 1918)

- 17. Dwight I. Long, K Co. (wounded 28 July 1918)

- 18. Dewey McAvoy, K Co., wounded by an explosive shell on 28 July 1918 in the attack on Hill 212 near Sergy. Was placed in an ambulance but died before reaching the hospital.

- 19. Daryl Mathers, K Co. (gassed 15 July 1918, Champagne-Marne offensive)

- 20. Orville E. Means, K Co., was asleep in a foxhole in the unit’s advance on the Ourcq River, was hit by an explosive shell and died instantly on 28 July 1918.

- 21. Fred Randle, K Co.

- 22. Frank Rice, K Co. (wounded, machine gun 12 Sept 1918, St. Mihiel drive)

- 23. Robert Risk, K Co. (arrived overseas 25 Oct 1918)

- 24. Glen Shuster, K Co. (wounded, machine gun 27 July 1918)

- 25. Wayne Simerman, K Co. (wounded by shrapnel 27 July 1918)

- 26. Earl T. Simerman, K Co. (landed overseas 5 Oct 1918)

- 27. Harry Swift, K Co., (gassed 27 July 1918)

- 28. Kenneth M. Swisher, K Co. (wounded 18 July 1918)

- 29. Claude D. Swisher, K Co., wounded in battle at St. Mihiel, died 8 Oct. 1918 at Base Hospital 9, Châteauroux, Indre

- 30. Floyd Wallace, K Co., killed on 28 July 1918 by an explosive shell as the unit advanced on the Ourcq River.

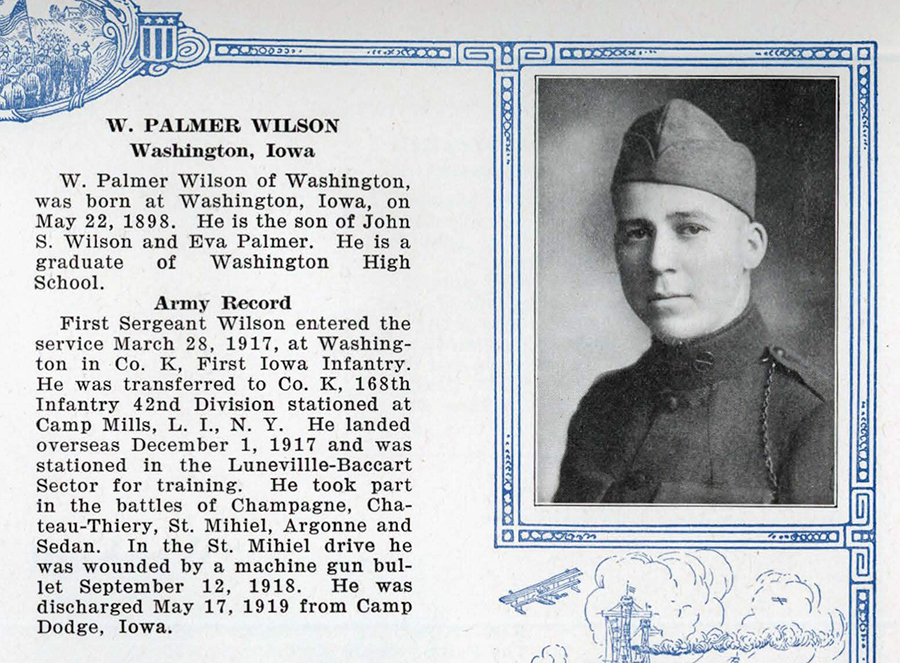

- 31. Palmer Wilson, K Co. – wounded 12 Sept 1918 in St. Mihiel drive

- 32. Ralph Woods, K Co. (discharged 12 Oct 1917 at Camp Mills, disability)

Also – entered service at Washington, IA, but was from Bayliss, IL: Jacob Schmitt, K Co.

From nearby towns and in the 168th Regiment (20 men; 6 wounded; 1 killed):

- 1. Glen S. Adams, Ainsworth, K Co. (arrived overseas 24 Oct 1918)

- 2. Howard C. Keiper, Ainsworth, K Co.

- 3. Oscar J. Coffman, Brighton, M Co. (cited for bravery in carrying dispatches through heavy barrage at Suippes on 15 July 1918)

- 4. Edgar C. Davison, Brighton, M Co. (wounded by shrapnel 18 Oct 1918 in Argonne; died 20 Oct.)

- 5. Vanis Foster, Brighton, M Co. (wounded 29 July 1918; shell shock)

- 6. Charles H. Hoppel, Brighton, M Co.

- 7. Hilton D. Houseal, Ainsworth, HQ Co.

- 8. Leslie Lewis, Wellman, K Co.

- 9. Rennie L. Moore, Ainsworth, K Co (wounded 29 July 1918, high explosive shell)

- 10. Charles M. Polton, Wellman, M Co. (killed in action 11 Oct 1918)

- 11. Moyle R. Prizer, Brighton, M Co.

- 12. Charles A. Quinn, Ainsworth, K Co.

- 13. Herman T. Spohn, Brighton, M Co. (machine gun wound on 28 July 1918 through sciatica nerve)

- 14. Dewey Godlove, Haskins, K Co. (wounded 16 July 1918, Champagne-Marne offensive)

- 15. Merle D. Chambers, Ainsworth, K Co.

- 16. Myral D. McGreedy, Haskins, K Co.

- 17. Terry Shafer, Brighton, M Co.

- 18. Samuel S. Stockman, Noble (born in Brighton), K Co.

- 19. Ora Lester Wasson, Wellman, K Co.

- 20. Harold Wilkins, Brighton, HQ & M Co. (wounded 31 July 1918)

Sources:

Essig, Maude. Private journal, Illinois Wesleyan University Historical Collection - http://collections.carli.illinois.edu/cdm/ref/collection/iwu_histph/id/1247

Frazer, Nimrod Thompson. Send the Alabamians: World War I Fighters in the Rainbow Division. University of Alabama Press, 2014.

Iowa: Washington County in the World War, (Published before 1920; available from Washington County Genealogical Society, Washington, IA.)

Robb, Winfred E. The price of our heritage: In memory of the heroic dead of the 168th Infantry. American Lithographing and Printing Company, Des Moines, IA, 1919. https://archive.org/details/priceofourherita00robb or see also: http://iagenweb.org/greatwar/poh/contents.htm

Roster of the Rainbow Division https://archive.org/details/rosterofrainbowd00johnrich or https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008230969

Taber, John H. The story of the 168th infantry. State Historical Society of Iowa, Iowa City, 1925. (2 Vols.) Digital version can be view online at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000403557. Individuals pages (but not the whole book) can be downloaded via this link.

Taber, John H. A Rainbow Division Lieutenant in France: The World War I Diary of John H. Taber. Ed. Stephen H. Taber. McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC. 2015.

Webster, Francis H. Somewhere Over There: The Letters, Diary, and Artwork of a World War I Corporal. Ed. Darrek D. Orwig. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK. 2016.

Wheelan, Mike. Personal memoirs. Privately published.