Agnes Swift

Agnes Leona Swift was my great aunt. She was born on the family farm near Ainsworth, IA, on 16 July 1880, daughter of John C. Swift and Mary Rimmer. She attended rural School No. 4 and elementary and high schools at St. James in nearby Washington. She earned a teacher’s certificate and taught in a country school in Highland township, as well as a private kindergarten in Washington for a couple of years. She was a close friend to the Alex and Ola Miller family and provided childcare to their daughters Barbara and Ophelia. In 1905, she graduated from St. Anthony’s Hospital School of Nursing in Rock Island, IL, and served as a private duty nurse in communities around Washington, IA. In 1907, she served as hospital matron (supervisor) at Pleasant View Sanitarium, Washington, IA, and later at the Keota Hospital until 1915.

.jpg)

Agnes Swift

In June 1911, Agnes was invited to accompany Dr. St. Elmo Sala, his wife, and Rosa Margrath, a surgical nurse from Rock Island, on a six-month tour of Europe. Dr. Sala, educated in public schools of Bloomington, IL and an 1892 graduate of the Keokuk (IA) Medical College, served on the medical staffs of St. Anthony, Mercy and St. Luke's Hospitals in Rock Island and Davenport. He wished to attend an X-ray training course at the Polyclinic Hospital in Vienna, and he generously invited Agnes and Miss McGrath to tag along. The trip included visits at medical institutions across Europe, as well as considerable sightseeing. The party made stops in Liverpool, London, Dublin, Edinburgh, Stockholm, Copenhagen, St. Petersburg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, Florence, Rome and other cities.

.jpg)

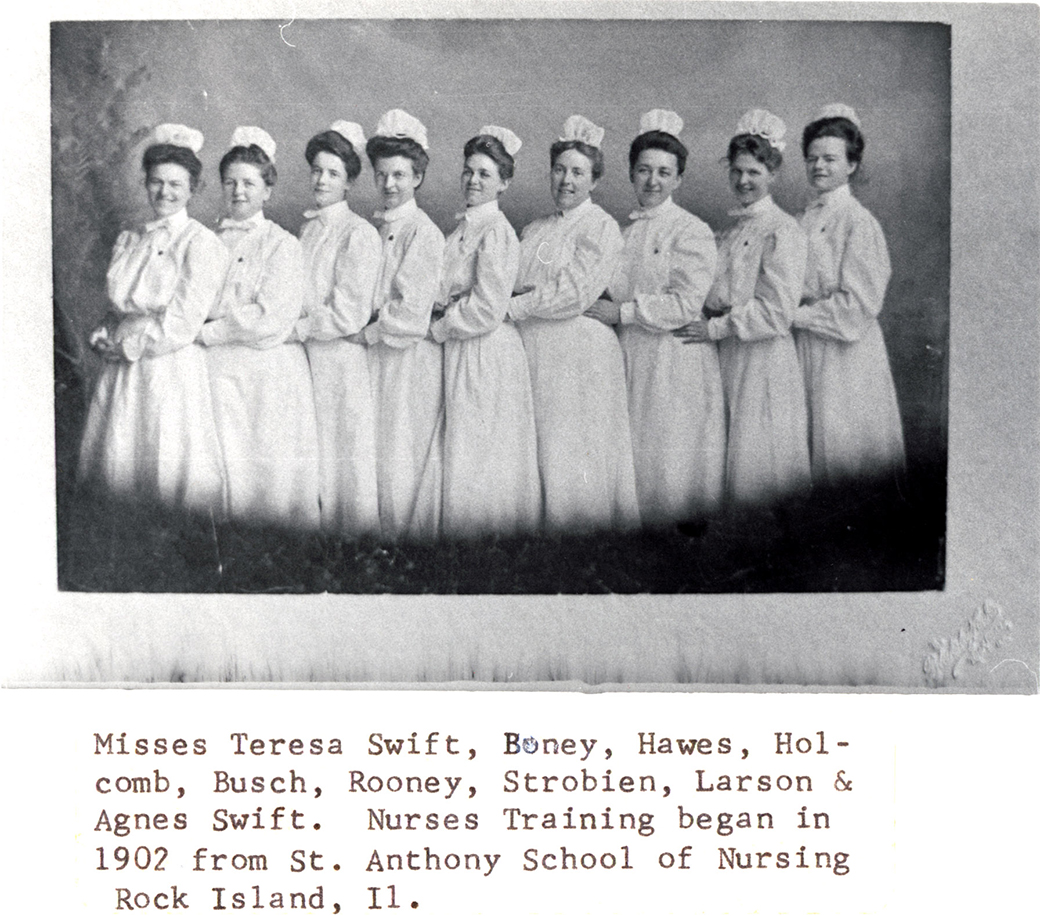

Graduating class of St. Anthony's Hospital School of Nursing, Rock Island, IL, 1905. Agnes Swift is in the middle row, far right. Her sister, Teresa Swift, is in the back row, second from the right. The others are unidentified.

The graduating class of 1905 included Teresa Swift, Kathryn Boney, Mary Hawes, Mary Holcomb, Julia Busch, Margaret Rooney (may have been a supervisor), Mary Strohbehn, Signa Larson, and Agnes Swift.

Agnes kept a daily journal and wrote frequent letters home. By pre-arrangement, she also sent regular accounts to her friend, Alex Miller, editor of the Washington Democrat, and they were published for the enjoyment of readers in her hometown. This trip not only provided an opportunity for education and insight into medical practices in other nations, it also allowed Agnes to make a brief visit to the village in Ireland from which her father had emigrated sixty years earlier. She found two first cousins of her father, writing home to him that one woman “was glad to see me, at least she had an awful frog in her throat when I left.” Her sister Martina later recalled an amusing incident on the trip which reveals not only Agnes’s rural upbringing but her mischievous sense of humor:

“They were dining at a fashionable London hotel, and the waiter took their order, asking them what they wished to drink. Agnes said, ‘Milk.’ The waiter seemed somewhat taken aback. ‘Do you wish the milk hot or cold?’ He returned a second time to ask, ‘Do you wish cow’s milk or goat’s milk?’ ‘Cow’s milk,’ she responded. He then returned a third time to ask, ‘Do you wish it in a glass or a cup?’ Agnes smiled at him and quipped, ‘Just wrap it in a napkin.’

At the outbreak of World War I, Agnes volunteered for overseas duty with Unit R, organized by Dr. J. Fred Clarke, of Fairfield, IA. She took her oath of office on 7 December 1917 in Washington, IA, and received orders to report to Camp Bowie, TX. She remained there until 1 February 1918, when she reported to Ellis Island to prepare for embarkation. On 16 February 1918, personnel of Unit R boarded the SS Carmania and sailed for France to become part of US Army Base Hospital 32 at Contrexéville, France.

Six hotels in the spa town of Contrexéville were leased from the French health ministry and converted for use as hospitals or lodging for hospital personnel. Base Hospital 32, originally planned for a capacity of 500 beds, was expanded to 1,250 bed before any American unit reached the town. A medical group from Indianapolis, arriving on 26 December 1917, provided personnel and equipment and began the task of cleaning and preparing the facilities. To provide additional personnel for the increased capacity, the War Department assigned Unit R to join Base Hospital 32. When Allied casualties mounted in September 1918, the hospital was ordered to increase its capacity once again (with no additional personnel) to an “emergency capacity” of 2,115 beds. By the time it was deactivated in February 1919, Base Hospital 32 had admitted 9,698 patients from 31 nations, including 189 German prisoners and many members of the local populace.

In her 24 March 1918 letter to family, Agnes describes the train journey to Contrexéville:

“Enroute across France we passed so many graves of French soldiers – of course the train was speeding along – there were some American soldiers on who had been on the road before – and all of a sudden – they took off their hats and stood with bowed heads – then we saw we were passing an American graveyard – the stars and stripes floating there from. As I say everybody choked up instantly. Nuff said.”

At Contrexéville, Agnes was assigned to Hospital A (Hotel Cosmopolitan), the primary surgical hospital. For much of her time with Base Hospital 32, Agnes worked only with eye injuries. She also had the difficult role of comforting patients when they realized they were blind. In a letter dated 18 May 1918 to her sister Julia, Agnes describes carrying for a local boy – “Capt. Byrnes did an enucleation yesterday morning. A poor French kid about 14 fell on a stick of wood and ruptured the eyeball. The awful part about it, he was totally blind in his left eye and the right could just see enough to get around. Now he is absolutely sightless and also has consumption. I often think what little we fuss about.”

.jpg)

Agnes (nurse on the left in the foreground) worked in the Eye Department of Hospital A (Hotel Cosmopolitan, Contrexéville)

After the Armistice, Agnes was granted leave from 10 to 16 December 1918, and she traveled with three other Base Hospital 32 nurses -- Madge Baldwin, Philomena Bauer and Bessie Whitaker -- to Lyon, Nice, Monte Carlo, Menton, Grasse, and Paris, returning to Contrexéville, “very tired but full of new and varied ideas of France & the wonderful A.E.F. and Red Cross.”

In December 1918, she describes the special Christmas hosted by for local children:

“The Red Cross had a Christmas tree in a large vacant room in Colonnade yesterday pm for the French children. It sure was entrancing. Needless to say, we stole away from the candy making a while to see those cute kiddos, their eyes snapping like jets. One of our corpsmen acted Santa Claus. They invited all children from 3 yrs. up – were 160. You see for most of them it was their first Christmas as they have not celebrated since the war. Couple of the sisters were there. Each youngster got the usual bag of candy, nuts, a toy and a nice little sweater.”

A few days later, Base Hospital 32 began packing up to go home. As others prepared to leave, Agnes joined 15 other nurses who volunteered to provide temporary relief for nurses at Base Hospital 90 in nearby Chaumont (AEF headquarters.) She served there from 17 January to 5 February 1919.

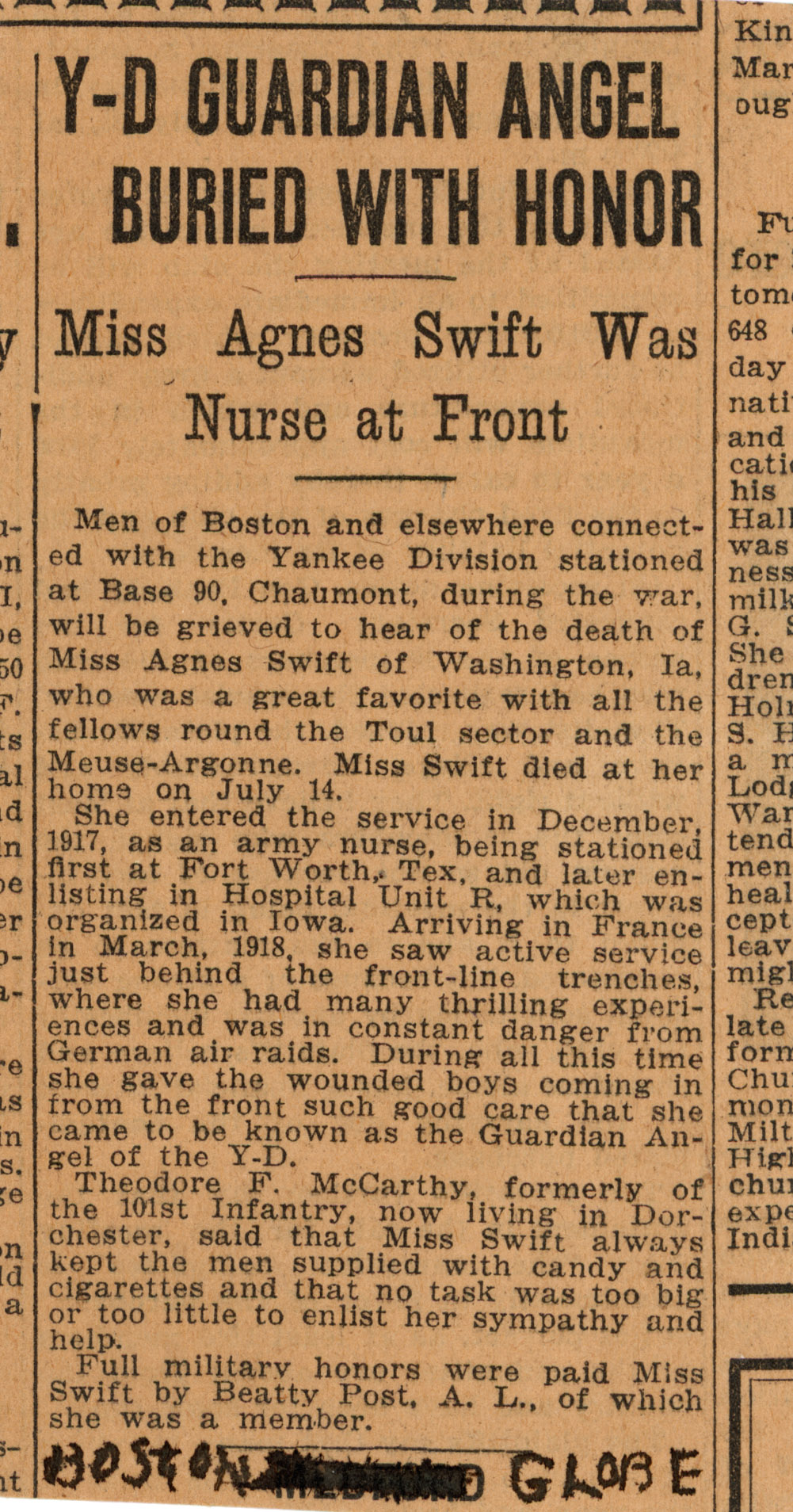

One of her many talents was candy making, which she put to good use when it was possible. When there was time and she or one of the men could find the scarce sugar, she would make batches of divinity or fudge for her ward. The patients appreciated this homey touch so much that one of the men from the Yankee Division drew a cartoon of Agnes and her ward, adding remarks to contrast her Iowa upbringing with their city life.

Agnes rejoined Base Hospital 32 in time to depart with the group on 19 February 1919, bound for home. But while most of the group boarded the SS America to depart from Brest on 4 March 1919, due to a lack of space, Agnes and eleven others were asked to wait for the next transport. She left France on 8 March 1918 on the USS Louisville and arrived in New York on March 22nd.

More than a few dying servicemen asked her if she would write to his wife or his mother to tell her they were comforted by the last sacraments or some special message they wanted to convey. One soldier left his gold ring for her to send to his mother, which she did. The grateful mother wrote a poignant letter in reply, a memento which remains to this day in the hands of Agnes’s family.

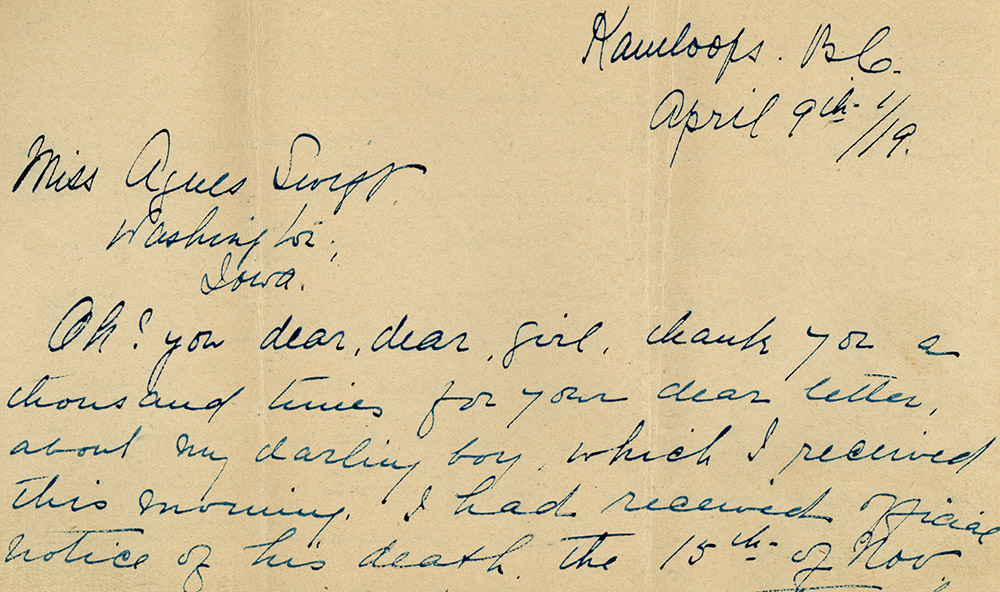

Letter from a grateful mother, who received a personal item of her son's from Agnes

Upon her return from overseas duty, Agnes had a bittersweet homecoming. She was warmly welcomed by family and friends in Washington but learned for the first time that her father had died in her absence. After a brief rest, she resumed private duty nursing and was employed for a short time at a hospital in Leon, IA, before returning to Washington to care for a sister who was dying of cancer.

While in service, Agnes developed a coronary problem, due to the long stressful hours in the operating room and war duty. Thousands of Allied wounded were sent to Base Hospital 32, which operated as an evacuation hospital for much of the time after mid-September 1918. The urgency to move patients was paramount, and opportunities for rest were rare. In a few short years after her return, Agnes’s health began to deteriorate. She rallied briefly, but hopes dimmed in the summer of 1923 when her health rapidly failed.

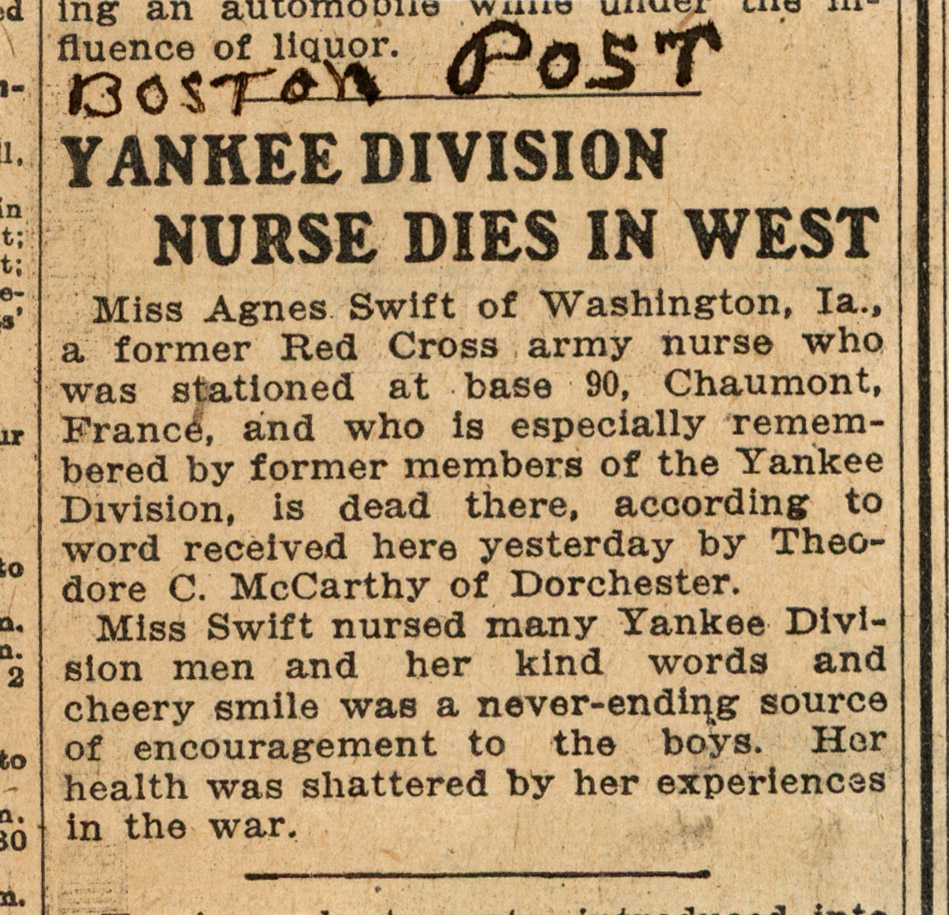

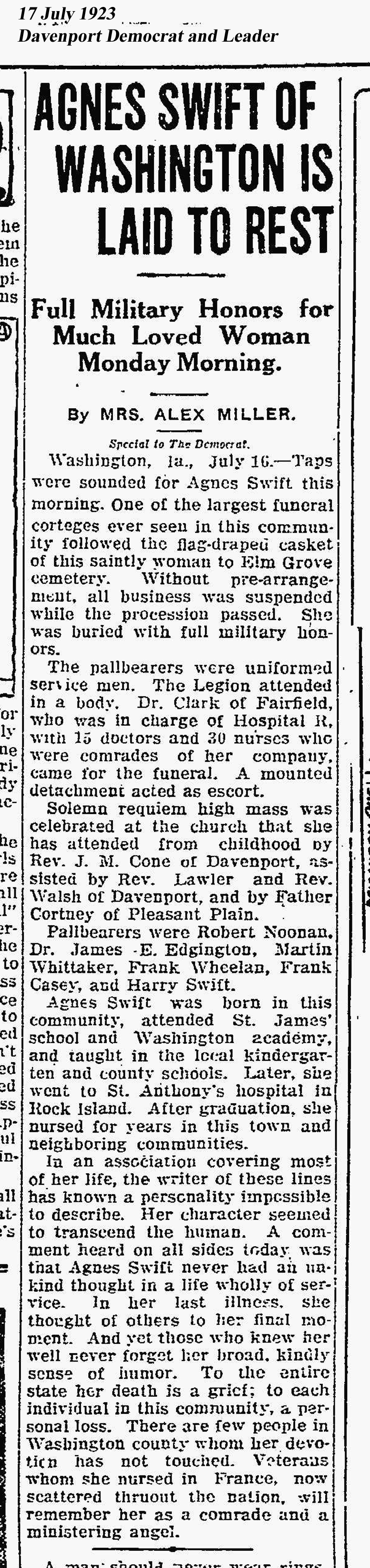

Agnes died in on 14 July 1923 in Washington, IA, and was laid to rest with full military honors in Elm Grove Cemetery on her 43rd birthday. The ceremony was attended by hundreds, including sixteen doctors and nurses of Unit R and grateful patients who traveled many miles to pay their final respects. One grateful patient in Boston, MA, reported her death to the newspapers in that city so the word would reach the men of the Yankee Division.

Sources:

Bailey, Sister Joan. Private collection of digital images of family photos and artifacts. Private collection.

Hitz, Benjamin D. A history of Base Hospital 32 including Unit R. Indianapolis, 1922.

Swift, Agnes. Unpublished letters to family and friends, Sister Joan Bailey collection

Swift, Agnes. Military record. Sister Joan Bailey collection.

For more information about Contrexéville and Base Hospital 32, see the following website: http://mollydaniel.net/contrexeville.