Kate Swift

Sarah Catherine (Kate) Swift Kate Swift, the fifth child born to John C. Swift and Mary Rimmer, was a steady force whose influence transcended her own generation and impressed upon her nieces, nephews, great nieces, great nephews and many cousins the admirable qualities of devotion and duty. When Sister Joan Bailey began collecting information, photos and records to tell the family story, it was to Aunt Kate she turned as the authority on the family tree and copies of old family letters. Because Kate had saved the letters written to her father from family members in Ballylee and Peterswell, we know much more today about the family connections and circumstances. The best description of Aunt Kate's personality and character is in the account written by her niece, Roberta Wheelan Clark, at the request of Sister Joan Bailey. Below is a full transcript of Roberta's profile, or you can listen to this recording of Roberta reading the story... or both. |

|

| Aunt Kate Aunt Kate Swift was fifteen years to the day older than my mother, Martha. I have often wondered what Kate’s reaction must have been to having a baby sister as a birthday present, for she already knew well enough what work such an event in the home would mean. It was Aunt Kate who kept the home going during some periods Grandma was not able to. Aunt Kate seemed destined to be the “Good Old Aunt” that so many families of that time had at least one of. Whether her status was chosen, appointed or just circumstantial, I don’t know. She had a strong sense of duty, but so did everyone then, each in his own niche. She never married, and it struck me as a surprise in later years that that was a matter of choice with her. Certainly she was the bulwark of the family, not only in caring for Grandpa and Grandma Swift in their later years, but as nurse, babysitter, seamstress and advisor for the rest of the family throughout her life. The things she didn’t ever have or get to do would have left the rest of us whining today, yet she was entirely uncomplaining, though never the doormat type. By the time my memories of Aunt Kate come into focus, she and Grandma were living in the house that Uncle Jim Walker had built on West Second Street, just up the street from the Baileys’ stucco house and just two blocks from the St. James Catholic Church that remained the predominant influence in Aunt Kate’s life through all of her days. Grandma was bedfast then; I can barely remember her sitting up sometimes in a little sewing rocker, and she was so tiny and thin that Aunt Kate could lift and carry her. The last year of Grandma’s life they both lived with Aunt Jule and Uncle, but I think that was probably harder on Aunt Kate than having all of the care of Grandma to herself. It hurt her pride to see someone else doing what she thought was her job. Aunt Kate did not, to me, seem so jolly as the other aunts; now, of course, I realize it was wondrous that she could smile at all, but smile she did, and loving she was, in her own quiet way. Some things even made her laugh, but she never seemed able to really let go with a laugh; instead a really good joke would provoke a series of closed-mouth sounds as her head nodded up and down. The antics of babies amused her; the quirks of mankind (more often womankind, in the person of her friends and relatives) amused her, and a good old Irish joke that is a long time in the telling and that ends with a joke on oneself – they amused her. She didn’t tell jokes. She laughed at them. Aunt Kate cared for everyone. Even while she was nursing Grandma through her last years and answering those countless weak pleas from the upstairs bedroom, she opened her house to her nephew and other young boarders. The ones I remember are Hubert Walker and Ed and Lester Miick. Indeed, it was at Aunt Kate’s house that Hubert discovered I could read before I went to school, and he had me perform for him every Sunday morning by reading the funny papers to him. It was also at Aunt Kate’s house, though not under Aunt Kate’s eye, that as a baby I stood up in her rocker and rocked back hard against the wall, cutting off the tip of the middle finger on my left hand. It healed with no problems except an unusual curve to the fingertip, but I’m told that it made things pretty exciting around Aunt Kate’s house that day. The sight of it has always made me feel a kinship with Aunt Kate, because she, too, had an injured hand. Her hand was twisted and misshapen from a childhood encounter with a hay rope pulley, but it never kept her from doing what she thought she was supposed to do. I can still see the potato peelings flying as she stood at the sink, the material gliding through the sewing machine guided by that little hand. Think of the wonders she performed with it all her life! Cooking at Aunt Kate’s house was done on a high white gas range which was the awe of us little kids because of the countless times we were cautioned not to go near it. The gas handles were within our reach. In the winter and in the cold months of spring and fall, refrigeration was by means of a box fastened on the kitchen windowsill. Aunt Kate opened the window, and there was the milk and cream and butter. The food that issued from those two sources was unforgettable. Aunt Kate’s cherry pies, latticed and losing juice, I remember yet, and her roast beef dinners. In fact, any time my roast beef gravy turns out to be good, I consider it good because it tastes like Aunt Kate’s. It really was no wonder the hobos came there from the nearby railroad tracks. The family said they thought the tramps had Aunt Kate’s house marked. It was many a man she fed a meal to on her gray doorsteps. I’m sure she followed Grandpa’ s Irish tradition “never turn a traveler from the door.” I can remember hearing her tell them, “No, I haven’t any money to give you, but if you want something to eat I’ll fix you a plate.” We kids were always so curious about her uninvited guests; I never could see why she wouldn’t let me sit right down there on the steps with the man and talk to him as he ate. That location next to the tracks was a mixed blessing. I loved to go out in the yard and count the cars as they went lumbering by in the daytime, but at night I was afraid of them. When I stayed all night with Aunt Kate I remember more than one time being a little miffed that she wouldn’t let me sleep in a bed by myself, but before morning came I was several times glad that Aunt Kate was there to cuddle up to when the 12 o’clock, the 2 o’clock, and the 4 o’clock trains woke me up. The house shook from them, and their roar was ten times louder than in the daytime. I was sure they were coming right in the bedroom! Although I think of Aunt Kate as stern, she probably gave each of us more individual attention than any of our other aunts, parents, or grandparents were able or willing to. She would sit down and play card games like “Concentration” and “Fifteen” with us for hours; side-by-side she would help us try to beat “Old Sol,” and she welcomed our help with her beloved crossword puzzles. The crossword puzzles were but one way she worked away at educating herself, for Aunt Kate had to stop school in the fifth grade to help at home. This devoted individual attention continued right on to the next generation, Aunt Kate often sent my kids, when they were little, little cereal box premiums, or any little surprises from the dime store. At Christmas Aunt Kate would find a way, out of her limited funds, to send something that would please little ones: a game of Old Maid, little hankies with fairytale characters printed on them, little notepads or pencils. In February came an envelope of Valentines. Some of these simple treasures are still in evidence here. The hankies were a hit with mother as well as the kids. They didn’t make any noise when they were dropped in church. Other entertainment at Aunt Kate’s house was the Sunday paper, a real joy for us because of the comics; there was Catholic Messenger and the Messenger of the Sacred Heart to read, but I more often went for her copies of Liberty Magazine (five cents a copy.) Or we could sit on the front porch and watch the neighbors, an unbelievable treat for a country kid such as I, for on Sunday mornings there was a regular parade of Mass-goers, the Lohbergers, George Wheelans, Dougalls, the Humbles. On weekdays there was a trickle of ladies going to and from their shopping, or wending their way to the button factory with their baskets of buttons and cards. This cottage industry paid them one fourth of a cent per card to sew the buttons on by hand. I seem to remember Aunt Kate doing a bit of it, too; although there was a general family resentment against the button factory, for it was felt that they had unjustly appropriated the rights to a method of coloring pearl buttons developed by Bob Lowe, one of their employees, and a cousin of Grandma Swift. I do know that Aunt Kate’s patience in trying to teach me the elements of stitchery did not extend to letting me sew buttons on cards, when to my childish mind, there lay the sure road to riches. One-fourth of a cent a card! We were insatiably curious about all of the passersby, and I, for one wanted to talk to them all, to follow them home, and to play with their kids, but the only ones Aunt Kate showed any real enthusiasm for letting me visit were Bessie Clancy’s kids, John and Ellen Humble, or the George Wheelan house, where “Kevvie” Julia McKevitt, ruled the roost. There, I had a feeling of belonging because Agnes made us feel welcome and George was related to Dad. George was a railroad section gang foreman, and he and his crew would stop and talk to us and tease us. It made us feel important. At George’s house I was always fascinated at the way he and Agnes and Kevvie would yell and scream and cuss at each other one minute and be laughing together over some jokes the next. In the Swift home I never heard that kind of yelling scene, and I didn’t realize it was all part of their kind of love for one another. Many years later when Bob and I were married in Rhode Island, Mother went with me to the wedding, but Dad stayed home, so when we got back to Providence after the ceremony, we sent Dad a telegram saying we were married and that we had put Mother on a train to Boston. The telegram was misdelivered and ended up at George Wheelan’s. George accepted it and enjoyed it all afternoon until Agnes came home from the bank. He showed it to her and said, “There, now, wasn’t that nice of Bobbie to send me that?” She would not laugh at anything ribald or sacrilegious, and the standard or what verged on sacrilege or blasphemy was a pretty high one. She had not much patience or tolerance for anyone who was unable to be good. They just should be good, and that was that. When more than one youngster stayed her house, we were under constant injunction from all the grown-ups to “be quiet” for the sake of Grandma, who, if she heard commotion would call from upstairs to know what was going on. So we had our own little “quiet” (I’ll bet they weren’t) activities, such as playing “Button, Button” on the stair steps, playing school, playing tiptoe hide and seek – that gave us a chance to get into the front vestibule and the hall closet with the mirrored door – and sending secret messages up and down the laundry chute in a tin cup on a string. There were three message centers for this – upstairs bathroom, kitchen and basement. In Aunt Kate’s cool spotless basement there was the pie cupboard with punched tin doors to snoop into, the wash bench to turn upside down and use for a sailboat. In the kitchen we were too close to the grown-ups to try much, but when we discovered that in the upstairs bathroom Aunt Kate kept a sack of lemon drops for Grandma to suck on, that prompted much of the desired silent activity. Aunt Kate’s social interest revolved around the Altar Society, in which and there always seem to be some minor feud with the autocratic Lou Wombacker, and the American Legion Auxiliary which she belonged to as the sister of a World War I veteran, Aunt Agnes. She devoted many hours and much work to both of these, and she may have also belonged to some kind of neighborhood card club, for she loved to play cards. Social interests certainly took a back seat to duty for Aunt Kate, however. Study and dependable, she was called upon by everyone to do things for them. After Grandma died, no old age pension or social security lay at hand for Aunt Kate; she got out and supported herself, usually by working as a live-in practical nurse. She kept her home, but later on rented the downstairs. She sewed for everyone, and in her spare time made quilts, aprons, table cloths, potholders. In today’s craft revival Aunt Kate could be a home industry old by herself. Her hearing began to fail her, and gradually, her eyesight. Yet she kept up one things and kept in constant touch with the far-flung members of her family. The only demand I ever knew her to make was “write in pen and write larger so I can read it.” Communication between the cousins was often kept going by Aunt Kate, who furnished the idea and much of the prodding to keep the round robin letters on the move. She spent hours upon hours constructing a quilt bearing the embroidered signatures of all of the cousins. It was she who kept track of family records, either in her head or written down, and it was she who was supposed to have the last word in family arguments over genealogy trivia, for, after all, who was the oldest of the six longest-lived sisters, and who, therefore, could remember more? Aunt Kate. |

A thankless life, you think? Yes, if you asked me, I would say it was, because I realize now how many times I failed to thank her when I should have, but if you could ask her, I think she did say, “No, what was I here for?” Why didn’t Aunt Kate get married? It was not for lack of opportunity, she once let me know, and there are worse things to be than unmarried, I know was her feeling.

Aunt Kate, 1935 Grandpa Swift must have had many hired men. They came and went with the seasons, but I always remember hearing the aunts talk and joke about one in particular, Groanie, because of his talents in tippling and in tall-tale telling. His name was Herman Groenwahl, and another reason and they joked about him was that the younger ones had eavesdropped on him as he talked in his sleep. I wonder now if Groanie had really been asleep at all, for what they heard were very flattering references to themselves; Martha or Martina, I forget which he said, was an angel. Kate, he liked. In fact, most of his mumbling references were favorable, except to Jule. Jule never cared for him and was wont to sniff at the rest of this story. But he did really like Kate. In fact, he wanted to marry her. He told me this himself. Kate must have said no. Mother told me once that Kate thought he drank too much. It later turned out that she was right. Groanie worked out the season and moved on. Now, Mother subscribed to several of the little magazines for farmers’s wives, which the subscribers by their letters, help to write. Probably fifty years after Groanie had left the farm in Ainsworth, Mother saw a letter in one of these little papers, Cappers Weekly, I think it was, signed by a woman named Groenwahl. Mother wrote to her and asked if she could be related to a man named Herman Groenwahl who had once worked in Iowa for her father. The woman wrote back that her husband was related to a man named Herman Groenwahl, but that the man was at that time a patient in the Illinois State Hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois. Mother wrote to me and asked if, on my next visit to Jacksonville, would I go to see the man and see if I could find out if it was the same one. With some misgivings, I went. The man I found said yes, he was, and he proceeded to spin so many tales I considered unbelievable that I knew it must be either the famous Groanie or else there was a good reason for him to be in a state mental hospital. I relayed the things he said to Mother, and the next time I was home, she and Aunt Gertrude and Aunt Kate agreed that the tales he told that related to life on the farm in Ainsworth were not tall tales, but true accounts that they had long forgotten. Subsequently I checked a few of the other things he told me and visited him some more. Gradually I learned that he had two families; his first wife and a number of children had all died in the flu epidemic of World War I, and his second family still lived in a town 50 miles or so from us. His grandchildren and my boys met on the football field several times. He had been committed to the hospital for the treatment of alcoholism. He asked me once, “Does Kate ever come to see you?” I said that she hadn’t ever, but that I hoped she would, and he said, “Ask Kate if she will come and see me.” Eventually Mother and Dad did bring Aunt Kate over; this was about 1948, and I did ask her, and she agreed to go see Herman. She and Mother and I went; they were all pleased to see one another and to visit; there was no great emotional reunion but a tear or two from Herman, and it did, as I said write the last chapter of that story. Since Aunt Kate was kindness itself, I know many prayers for Herman went to heaven after that visit. Kindness she was, but firm, firm, firm in her beliefs. I never thought of not minding Aunt Kate when I was left with her as a child; she carried so much of an air of authority. She didn’t worry overmuch about the psychology of child behavior; I remember Mother saying Aunt Kate thought older children should not be jealous of younger ones because they just shouldn’t be jealous. Never mind why; don’t do it. How surprised some of my high school kids have looked when I tried that on them! Once, I remember Aunt Kate telling me at lunch to eat up all my lunch before I went out to play. Over and over: “If you don’t eat it, there won’t be any more until supper.” Whatever lunch was, play must have been more attractive, because I resisted the admonition. In an hour or so, away down the street I heard tinkling bells. The ice cream wagon! The bells were on the harness of the horses which pulled the wagon, and that plodding horse allowed children plenty of time to – and to the house and wheedle nickels before it arrived. But this day, no nickel was forthcoming, only the answer, “No. You didn’t clean up your plate, so you don’t need an ice cream cone.” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Nowhere else would I have gotten that answer, not at Aunt Jule’s, not at Grandma Wheelan’s, and I know now that it was not that Aunt Kate didn’t have the nickel. She would probably have much rather bought me the ice cream cone, but it was a MATTER OF PRINCIPLE. So was her whole life. |

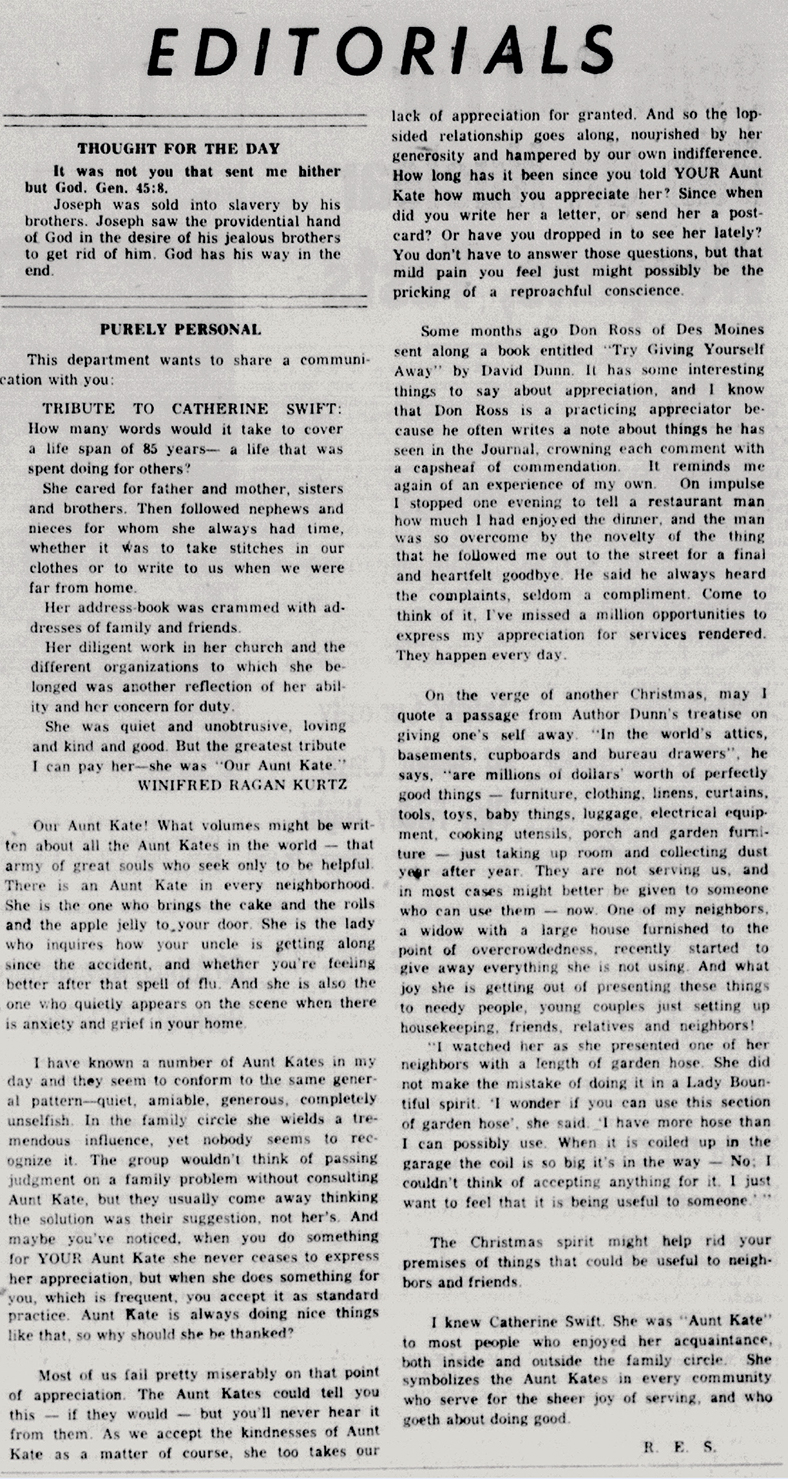

From the Washington (IA) Evening Journal, November 23, 1957. Written by editor R. E. Shannon. |

| Other stuff and 2023 trip |

|

back to the top |