Ocean Travel in 1851

The Leaving of Liverpool

The Great Western sailed from Liverpool in 1851, carrying my ancestors from the Swift and Rimmer families. The Rimmers lived in Brewood, Staffordshire, England a day's journey (80 miles) to the southeast of Liverpool. The Swifts came from County Galway in Ireland, and they would have traveled to Liverpool to await boarding for the trans-Atlantic passage at the Waterloo Docks in Liverpool. How the Swifts arranged for their passage is not known, but it is likely that they relied on assistance from others and probably used pre-paid tickets because neither John C. nor Mary was able to read or write. Arranging for pre-paid tickets through a licensed agent was one way to avoid exploitation by unscrupulous "man-catchers" for which Liverpool was widely known.

"The Leaving of Liverpool," an Irish folk song popularized in the 1960's by The Dubliners and the Clancy Brothers, was a revival of a capstan chantey, a tune sung by sailors more than a century earlier. As with many folk songs, the lyrics vary from one version to the next. The Dubliners' version of the tune starts with the lines

Farewell to Princes Landing Stage,

River Mersey fare thee well.

I am bound for California,

A place I know right well.

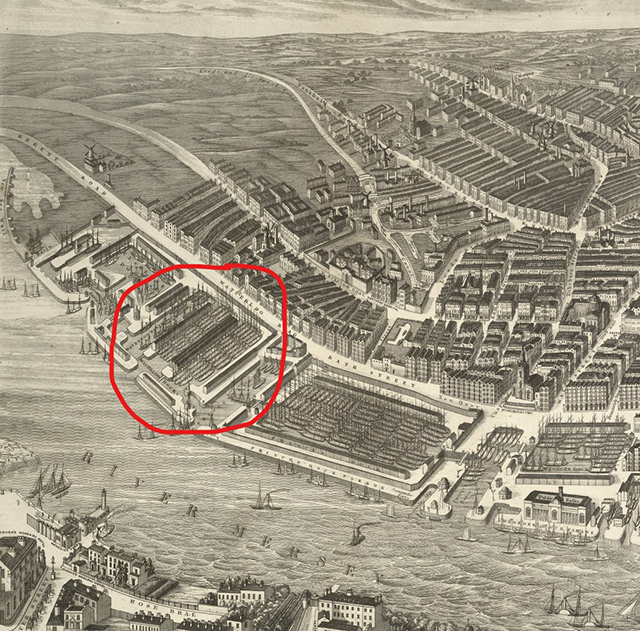

The Princes Landing Stage refers to an area of the docks at Liverpool, from which sailing ships departed. It is named for Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Today the renovated brick warehouse buildings on this site house a range of museums, restaurants, cafes and bars known as the Royal Albert Dock. During the mid 19th century, most of the emigrant ships heading for Canada or the United States, including those of the Black Ball Line, sailed from the Waterloo Docks, a location just a few meters north on the Mersey channel from the Princes Landing Stage.

Liverpool in 1850 was overrun with persons seeking to sail to North America. The successive years of the failed potato crop in Ireland, starting in 1845, and the corresponding indifference in Britain to this calamity and the ensuing poverty and starvation among the Irish populace drove millions to leave Ireland for better conditions. Overall, an estimated 1.5 million people crossed the Irish Sea and headed for Liverpool.

Emigrants arriving in Liverpool could expect to find inhospitable conditions. Throughout much of the 19th century, the city had a high crime rate and plenty of unscrupulous characters who preyed on emigrants seeking passage. Conditions on board some ships were so notorious that Parliament ultimately passed the Passenger Act of 1849 (see this link for a description of the abuses of emigrants and this link for an abstract of the rules set for voyages to North America).

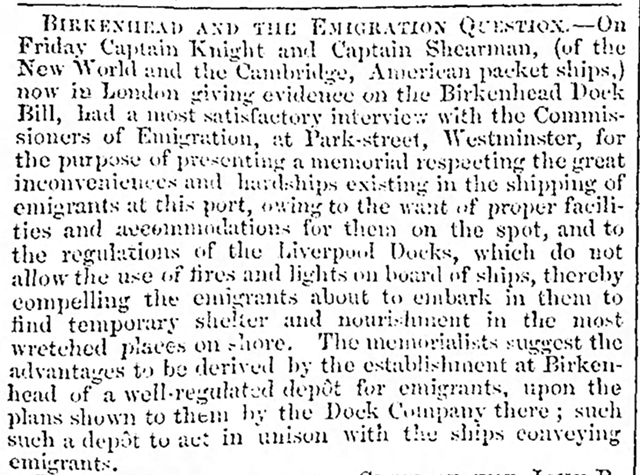

Ships did not always depart on the date advertised, and passengers were generally not allowed to board the ships until 24 hours before sailing. In the meantime, destitute persons were left to their own devices for finding shelter. This item from the Liverpool Mercury, Apr 23, 1850, notes that Captain Shearman and another ship's captain provided supportive testimony to the Commissioners of Emigration regarding the need for better accommodations for emigrants:

Birkenhead and the Emigration Question - On Friday Captain Knight and Captain Shearman, (of the New World and Cambridge), American packet ships,) now in London giving evidence on the Birkenhead Dock Bill, had a most satisfactory interview with the Commissioners of Emigration, at Park-street, Westminster, for the purpose of presenting a memorial respecting the great inconveniences and hardships existing in the shipping of emigrants at this port, owing to the want of porpoer facilities and accommodations for them on the spot, and to the regulations of the Liverpool Docks, which do not allow the use of fires and lights on board of ships, thereby compelling emigrants about to embark in them to find temporary shelter and nourishment in the most wretched places on shore. The memorialists suggest the advantages to be derived by the establishment at Birkenhead of a well-regulated depot for emigrants, upon the plans shown to them by the Dock Company there; such a depot to act in unison with the ships conveying emigrants.

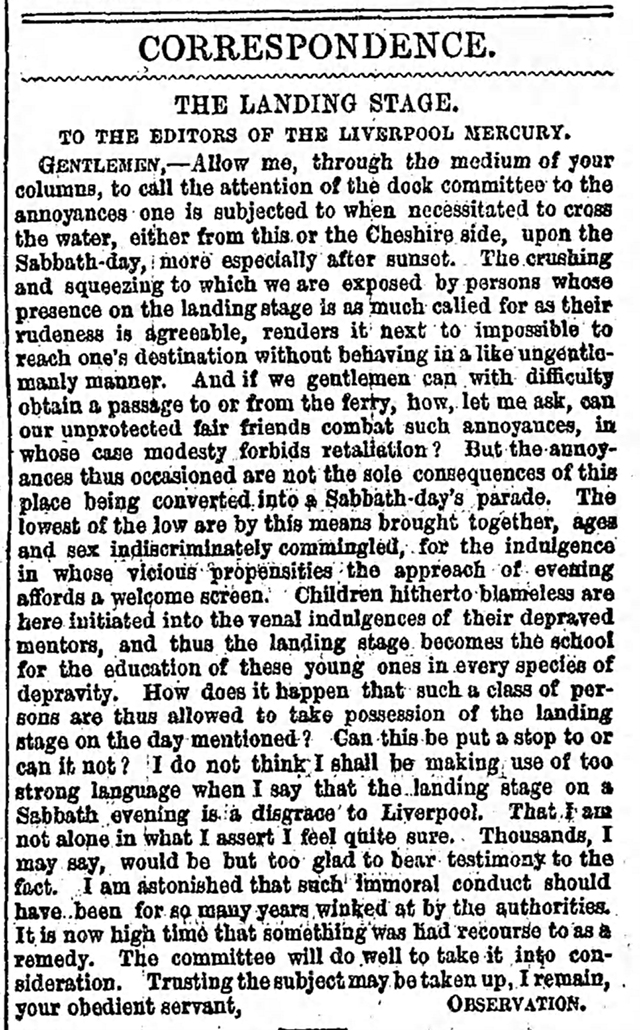

More genteel customers of the passenger ships were perhaps less empathetic, as illustrated by this letter to the newspaper, complaining of the rudeness of people at the Liverpool docks:

The question of the passenger fare for the voyage depended on several factors. Fares for first-class cabins were naturally higher than rates for second-class berths or steerage. Rates for the westbound passage, i.e., Liverpool to New York, were higher than rates for passengers heading the other direction. Fares for steamship passengers were higher than those for sailing ships, and fares on newer ships were higher than those for the older ships in the line. Though our family has no record of what our ancestors paid for their voyages, the best estimate is that it was somewhere between £5 and £25 for each adult on the westward voyage (an amount approximately equivalent $500 to $800 in 2020 funds). This was of course for passage in the steerage deck. (See a depiction of below-deck conditions on a sailing ship by marine artist Rodney Charman.)

After the enactment of the Passenger Act of 1849, the ship's master (captain) was required to supply food provisions for each passenger, in addition to what they may themselves bring. The minimum weekly ration, per adult passenger, was stipulated:

3 quarts of water daily

2½ of bread or biscuit (not inferior to navy biscuit)

1 lb. wheaten flour

5 lbs. oatmeal

2 lbs. rice

2 ozs. tea

½ lb. sugar

½ lb. molasses

The law required that the provisions were to be issued in advance and not less than twice a week. The law also stated that, "5 lbs. of good potatoes may at the option of the master be substituted for 1 lb. of oatmeal or rice, and in ships sailing from Liverpool, or from Irish or Scotch ports, oatmeal may be substituted in equal quantities for the whole or any part of the issues of rice."

Our family stories note that during their westward voyage on The Great Western, our ancestors ran short of food provisions. John C. Swift's recollection was that, while they did not run out of food altogether, the adult passengers in steerage were reduced to eating the peelings of potatoes and reserving the better part of the spud for the children to eat.

Another notable requirement for the steerage accommodations was that passengers were required to provide their own bedding. This stipulation and the lack of facilities for proper hygiene among a crowded population of persons fleeing poverty undoubtedly led to ideal conditions for the spreading of lice, bed bugs and diseases such as typhus. The voyage made by the Swift and Rimmer family members was on a new ship, returning from her maiden voyage out of New York. Just a few months later, on her second trip from Liverpool, The Great Western sailed into New York with more than 700 passengers, 91 of whom were suffering from typhus. Captain Shearman contracted typhus from that passage and died one month later.

Martin and Bridget Swift and the Cushlamachree

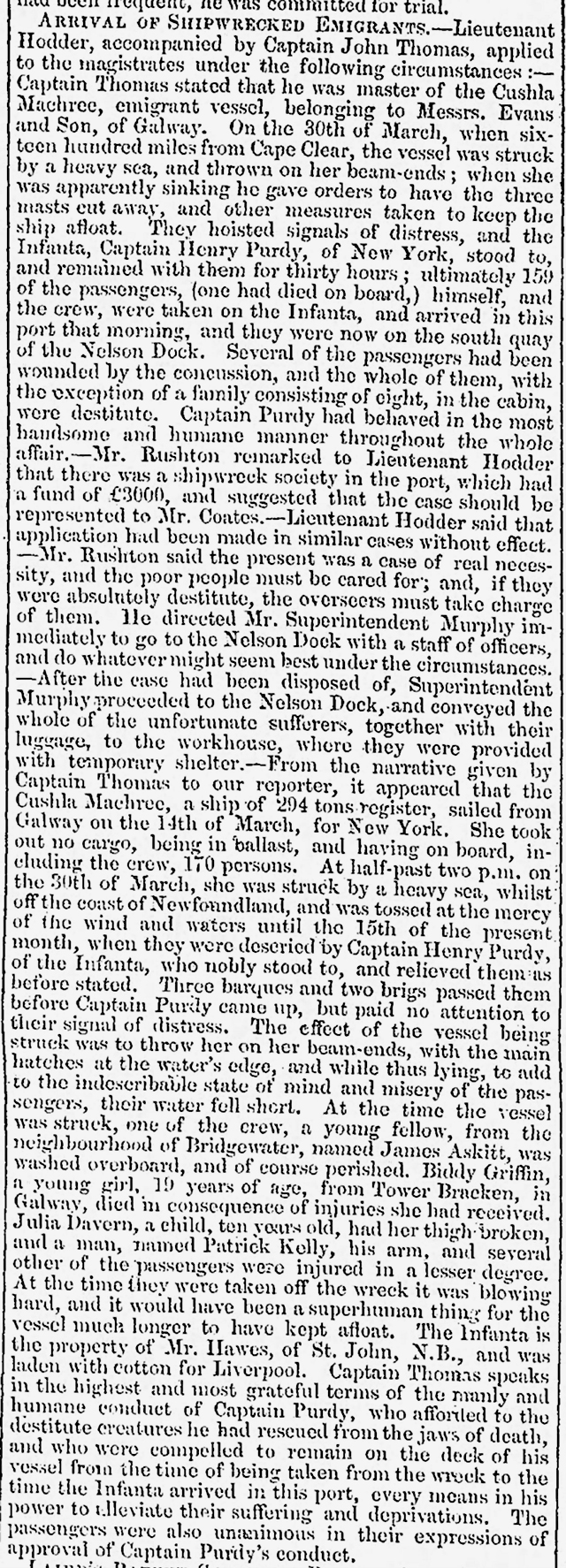

Martin and Bridget Swift, who had sailed for America three years earlier than their siblings John C. and Mary, traveled on a voyage that embarked from Galway with the British ship the Cushlamachree, commanded by Captain John Thomas. The Cushlamachree was a smaller vessel, roughly half the size of the Great Western, and carried fewer than 200 passengers. The voyage taken by Martin and Bridget docked in New York on Apr 23, 1848 after an apparently unremarkable trip. Some subsequent passages of the Cushlamachree, however, were not so smooth. In January 1849, she arrived in New York after an arduous 57-day winter crossing from Galway, and the following year was in a desperate situation after she ran into heavy seas off the coast of Newfoundland. She was tossed about for nearly two weeks before being rescued by a passing ship. See the account below from The Liverpool Mercury.

All things considered, I think it is a miracle that my ancestors found the means to emigrate and made the voyage safely.