Captain David S. Shearman, Jr.

Riverside, at 182 N. Water Street, Poughkeepsie, NY, home of Captain David S. Sherman, Jr.

David Sands Shearman (1802-1852) was the son of Captain David Shearman (Sr.) and Ann Tucker, Quakers of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. He married Hepsa Hathaway Howland, daughter of Pardon Howland (1777-1821) and Hepsa Hathaway (1777-1856), Quakers of New Bedford Monthly Meeting. Hepsa's father was also a sea captain.The family name also appears in records spelled "Sherman," Shareman," and "Shurman," but the preferred spelling is "Shearman."

In 1834, Captain Shearman, Jr., moved with his family from New Bedford to Poughkeepsie, NY. Results of a search for "Shearman" in the online database at https://whalinghistory.org/ indicate that between 1833 and 1840, he served as an agent for both the Poughkeepsie Whaling Company and the Duchess Whaling Company.

Whaling ships were gone for years at a time. For example, the first whaling company in Poughkeepsie - the Poughkeepsie Whaling Company - sent its first vessel, The Vermont, off to sea in 1832, and it returned three years later with $16,000 worth of cargo (also minus its captain, killed in a stabbing incident which likely involved his crew) .

Captain Shearman fathered 12 children with his wife, Hepsa. At least two of his sons were also seafarers - Joseph T. Shearman became a ship's captain, though later in life he settled in a business (in Stroudsburg, PA, and later in Ohio and Kentucky). Son Abraham Shearmon was sadly lost at sea in 1862. One family genealogy states, "he was last seen floating on a raft in the China sea."

In 1837, when the U.S. experienced an economic depression ("The Panic of 1837"), the whaling companies in Poughkeepsie folded. In her history of the whaling industry in Poughkeepsie, S.T. Smith says, "Though it officially went into receivership in 1848, the Dutchess Whaling Company was dead by 1845." The full text of this 19-page article was printed in the 2009 Duchess County Historical Society Yearbook, which is available online at https://dchsny.org/yearbook. Download the 2009 issue and go to page 364 in the downloaded PDF file.

Packet Ship Trade and the Black Ball Line

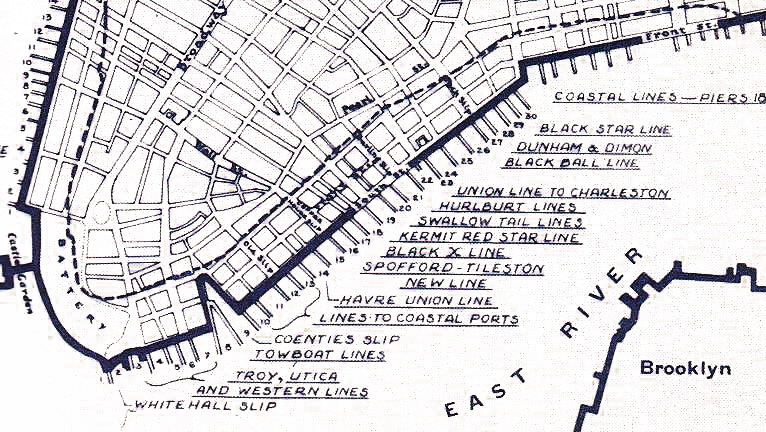

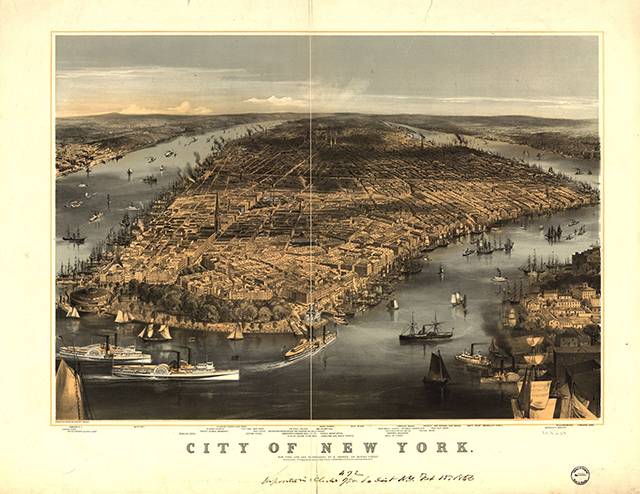

It was around this time, that Captain Shearman took up work as an agent for the Black Ball Line, transporting merchandise and passengers across the Atlantic. Based at Pier 23 on the East River in New York City, the company was founded by a group of New York merchants in 1817 under the name Wright, Thompson, Marshall, & Thompson Line and with the purpose of providing scheduled voyages between New York and Liverpool. The idea of scheduled voyages, or packet trade, had been tried before, without much success, but when the Wright, Thompson, Marshall & Thompson line demonstrated that their ships would indeed leave port on a regular schedule, their business became more attractive to merchants who wanted a dependable movement of their goods. The Wright, Thompson, Marshall & Thompson Line began operations in 1818 with four packet ships. The ship James Monroe sailed the first voyage (see interesting history of the James Monroe at this link.) The company was known for a while as the Old Line and then, after the 1840's, as the Black Ball Line.

Many ships for this line were built by William H. Webb, the New York shipbuilder who has been called America's first true naval architect. At the age of 24, he inherited his father's shipyard, Webb & Allen, and discovered it was bankrupt. Undeterred, Webb bought out his father's partner and began crafting ships based on his own designs. His attention to detail and appreciation of the finer points of engineering earned his shipyard an enviable reputation as the builder of fast and seaworthy vessels. By the time he retired from shipbuilding 29 years later, his company had built 135 ships. The final ship built by the William H. Webb shipyards was the steamship named The Charles H. Marshall. When she was completed in 1869, Webb permanently closed his business. He is probably better remembered as a philanthropist, though, having endowed an institute for nautical engineers, The Webb Institute, with sufficient funding such that - to this day - none of the students are charged tuition. Fans of the Batman movies might recognize the current home of the institute, Stevenson Hall, as the building used for exterior shots as Wayne Manor. It also appeared in the 1998 movie Great Expectations.

The packet ships of the Black Ball Line were easy to recognize, flying a red pennant with a black ball in the center on her main truck. (A later competitor a company organized in Liverpool by James Baines and operating under the same name, even adopted the same red pennant.) Another black ball, much larger, was sewn on the fore-topsail of the ships in the New York-based Black Ball Line, high up where it would be visible even when the sail was partly furled.

The packet trade took a while to catch on, but when it did, it was wildly successful, and other shipping firms scrambled to offer similar services. In 1836 the Line passed into the hands of Captain Charles H. Marshall, and he gradually added the Columbus, Oxford. Cambridge, New York, England, Yorkshire, Fidelia, Isaac Wright, Isaac Webb, the third Manhattan, Montezuma, Alexander Marshall, Great Western, and Harvest Queen to the fleet. Of these, Captain Shearman commanded the Montezuma (temporarily in 1849), the Yorkshire (1850), and the Great Western (1851 and 1852).

The author of an interesting history about the sailing vessel James Monroe states, "The term 'packet,' later used to designate the famous 'line' ships, had from the first been loosely applied and has caused much confusion. Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as a packet design; before 1817 'packet' meant any vessel, whether brig, sloop or square-rigger, that functioned as a carrier of freight. The Black Ball Line called its ships packets to distinguish them from the irregular 'regular traders.' The name clung to scheduled vessels through the evolution of naval architecture from the bulbous prow and broad beam of the Black Ballers to the sharper-bowed more graceful ships of the clipper era."

The traditions (and sometimes unsavory reputation) of the Black Ball Line are enshrined in songs from the era. Sea chanteys (or shanteys) were tunes sung by crews of the merchant ships to coordinate work rhythms. Most people are familiar with tunes such as "Blow the Man Down" or "Early in the Morning" ("what do we do with a drunken sailor"), but few know that "Shenandoah" has its origins as a sailor's song. Like most folk songs, the sea chanteys may have several versions with differences in the lyrics and/or the tune. Some versions of "Blow the Man Down" make mention of the Black Ball Line. For example one rendition goes like this:

As I was a-walking down Paradise Street,

A brass-bound policeman I happened to meet.

Says he, "You're a Black Baller by the cut of your hair;

I know you're a Black Baller by the clothes that you wear."

"Policeman, policeman, you do me great wrong;

I'm a Flying Fish sailor just in from Hong Kong.

Woody Guthrie sings "Blow the Man Down":

"The Black Ball Line" is an example of a halyard chantey, a tune used to coordinate the actions of pulling the halyard or a rope used to hoist sails (though the audio of this version below is sung at a tempo much too fast for the original purpose):

For more about the history of sailors' songs, see this monograph available from the Kendall Whaling Museum: Sea Chanteys and Sailors’ Songs: an Introduction for Singers and Performers, and a Guide for Teachers and Group Leaders by Stuart M. Frank. KWM Monograph Series #11. 2001.

In New York, the ships of C. H. Marshall's Black Ball Line arrived at Pier 23 on the East River. Today that approximate location is where the Brooklyn Bridge connects to Manhattan.

The packet ship voyages were much shorter than those of the whaling ships. The average passage of packets from New York to Liverpool was 23 days eastward and 40 days westward, but speed records for the sailing ships of this era were recorded for half that time. In 1830, the Black Ball Line's Columbia made a remarkably fast westward crossing in 15 days 23 hours. But usually, passengers embarking at Liverpool on one of the sailing ships bound for New York could expect the journey to take 40 days. This is noteworthy in the context of the Swift and Rimmer family story of their westward passage of 41 days being "unusually long." It was actually only a day or two longer than average for the westward travel on a sailing ship of that era.

While Captain Shearman likely welcomed the shorter voyages of the packet trade, that's not to say that everything went smoothly. Consider, for instance, his experience with the Yorkshire, on its 1851 voyage out of Liverpool. As reported in the London Morning Post on Feb 24, 1851, she

"sailed from Liverpool on the 4th of January, with a general cargo and about 350 emigrants (chiefly the poorest class of Irish), for New York. When off the banks of Newfoundland it appeared she was struck by a heavy sea, which so much injured her rudder that she was obliged to bear up for Liverpool again. On Wednesday last she reached Holyhead, and struck on the rocks there, but was towed off by the Dublin Company's steamer Prince of Wales, Captain Shearman having sent ashore for that steamer's assistance. The Prince of Wales, however, was not found sufficiently powerful to tow the large ship when she got into the tideway, so the ship let go her anchor, and the Prince of Wales returned to harbor. In the meantime, the Anglia steamer, Captain Warren, belonging to the Chester and Holyhead Company, got up her steam, and on the Yorkshire hoisting a signal of distress, went off to her assistance, and, with the aid of the Prince of Wales, again succeeded in towing her into harbor. Two steamers have since come round from Liverpool, and taken the passengers off. The cargo is valued at 25,000l."

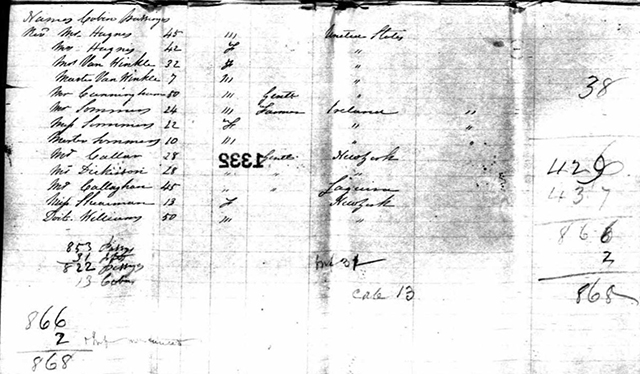

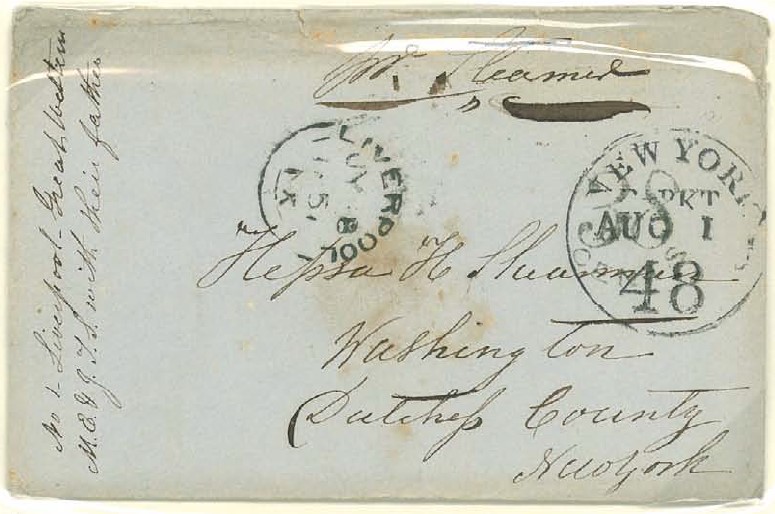

Later that year, Captain Shearman took command of the newest ship in the Black Ball Line, the packet ship the Great Western, departing New York on June 14 for Liverpool on her maiden voyage. They arrived on July 15 after a slow voyage. In a letter to his wife, Captain Shearman reports that they nearly had a mutiny and he had to put a man in chains to quell it. He claims that he had "one of the most inferior crews that I have ever commanded." The record of family correspondence also indicates that two of Captain Shearman's children were with him in Liverpool - son Joseph T. and daughter Mary Eliza. On the return voyage to New York, the ship carried 868 passengers, including 13 cabin passengers. "Miss Shearman" was among them.

An image of a page from the passenger list for the return trip to New York includes "Miss Shearman," age 13 from New York among the cabin passengers.

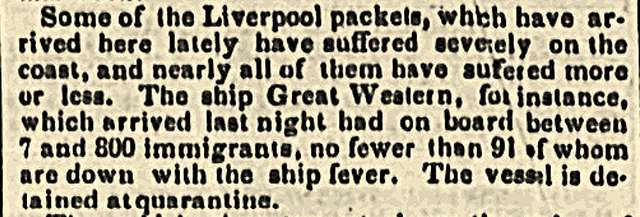

Captain Shearman made only four voyages with The Great Western, and it was on his second trip from Liverpool, departing that city on December 10, 1852, that he contracted "ship fever" (typhus).

After being quarantined in New York upon arrival, Captain Shearman somehow found his way back to his family in Washington, NY (20 miles northeast of Poughkeepsie), where he died on February 10, 1852.

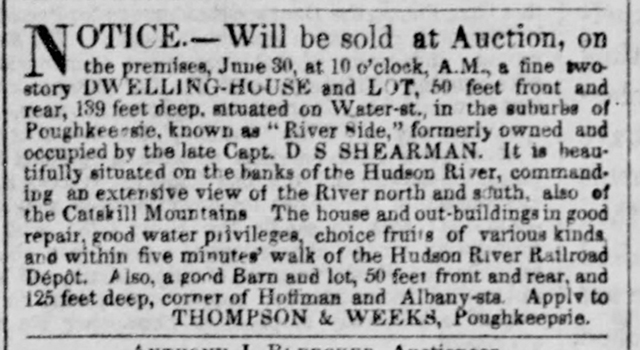

After her husband's death, Hepsa H. Shearman advertised the residence at 182 N. Water Street in Poughkeepsie for sale and ultimately put it up for auction.

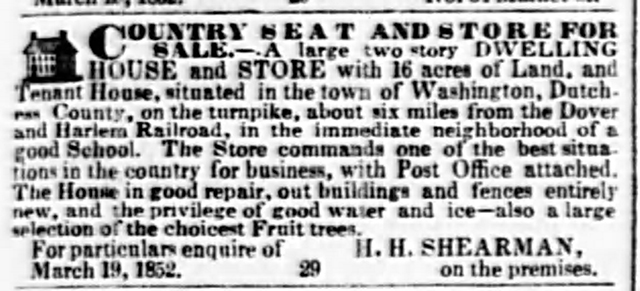

The family also held property in Washington, which was sold. Hepsa then returned to New Bedford, MA, where she lived for several years until she moved to Philadelphia and later New York and lived with her daughter, Mary Eliza.

The Poughkeepsie property, pictured at the top of this page, passed through the hands of several owners until the state of New York acquired it and 13 other properties in 1960 to secure a right-of-way for state Route 9 along the Hudson River. The property was destroyed in 1961 to make way for highway construction.

Hepsa Howland Shearman was a cousin to Hettie Howland Robinson (1834-1916), who inherited considerable wealth from the Howland family fortune (accumulated from their whaling operations in New Bedford, trade with China and timely investments). Hettie inherited the bulk of her wealth from her father, Edward M. Robinson, and an aunt, Sylvia Ann Howland. Having acquired a keen instinct for bookkeeping and investments from her grandfather, Hettie became the country's richest woman during the Gilded Age. She had a reputation for being extremely thrify, and some would say miserly (she acquired the nickname "the Witch of Wall Street"). She died in 1951 leaving an estate with an estimated value of $200 million. Most of it was left to colleges, universities, hospitals and other charities. Surviving descendants of her cousin Hepsa Howland Shearman also received a portion of the inheritance.

Interesting Coincidence

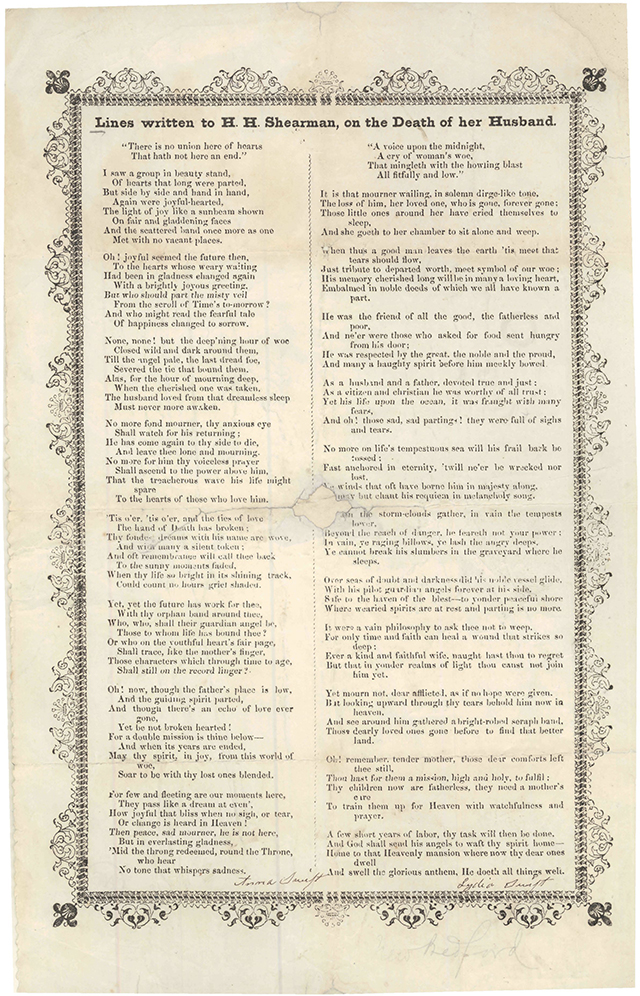

Following the death Captain Shearman, a page of two verses memorializing her loss was published. An image of what appears to be a broadsheet is preserved in a collection of epherema from the era. An unknown hand has annotated the page with "New Bedford" at the bottom of the page and the names "Anna Swift" and "Lydia Swift" are inscribed below the poems. These women were presumably close friends to Hepsa. Though I cannot be sure they are the same, I find a Lydia Swift (née Almy) (1828-1857) and a Johanna Swift (1826-1884) among persons listed in the burials at the Nine Partners Cemetery, Millbrook, Duchess County, NY. They were sisters-in-law. This Swift family, descended from William Swift, a 17th-century immigrant from Essex, England, is no relation to my immigrant ancestor, John Connnell Swift.