Finding Margaret

The value of educating your daughters

I enjoy discovering family stories and diving down rabbit holes. Sometimes, I find rabbits, too!

With this week's discovery, it occurred to me (again) how much gratitude I owe my great-great-great-grandmother for something that she did (she thought) for her own fulfillment – she insisted that her daughters learn to read and write.

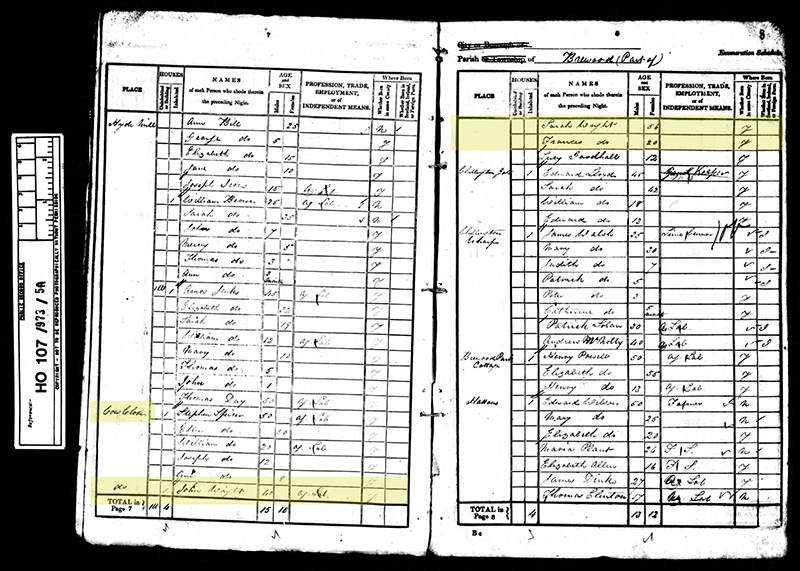

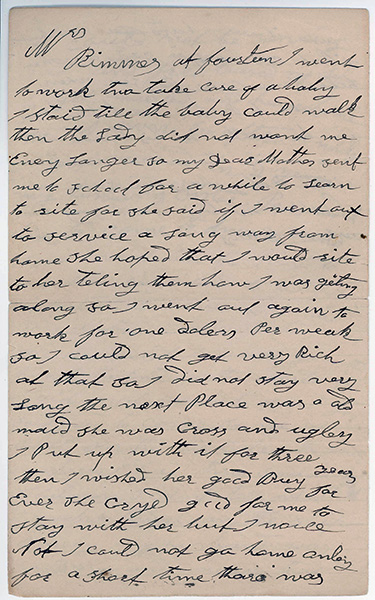

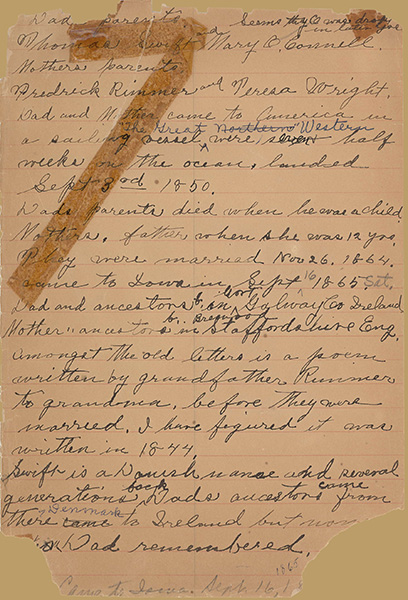

Sarah Howell Wright, who lived in Staffordshire, England at the end of the 1700's and the first half of the 1800's, was the mother of at least six children, and four of them were daughters: Catherine, Ann, Frances, and Teresa. As young women, they worked in domestic service, which often meant living away from their home and doing the cooking, cleaning and child care for another family. Sarah insisted that her daughters learn to read and write because, as her daughter Teresa wrote, "if I went out to service a long way from home she hoped that I would rite to her teling them how I was geting along."

So Teresa got an education, a rare thing for a woman in the working class at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

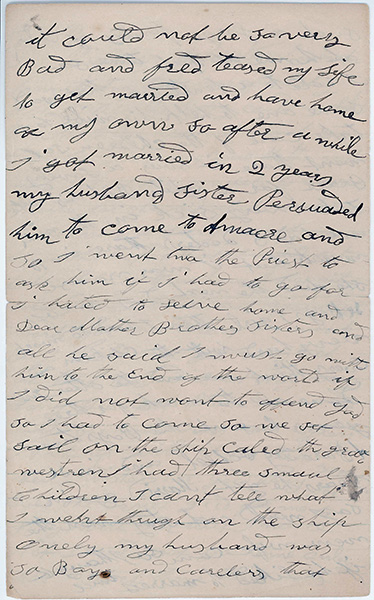

And it was a good thing that Teresa could read and write because after she married and had some children, her husband decided that they should move to America. She did not like the idea, as she wrote: "my husband sister Persuaded him to come to Amacre [America] and so I went two the Priest to ask him if I had to go for I hated to leive home and Dear Mother Brothers Sisters and all. He said I must go with him to the end of the world if I did not want to offend God. So I had to come."

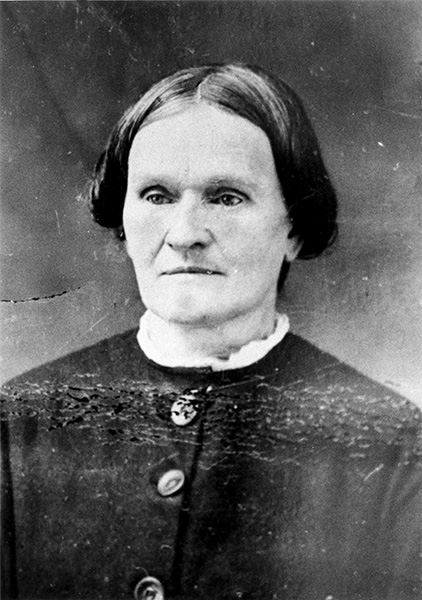

Teresa Wright Rimmer never saw her mother, brothers or sisters again.

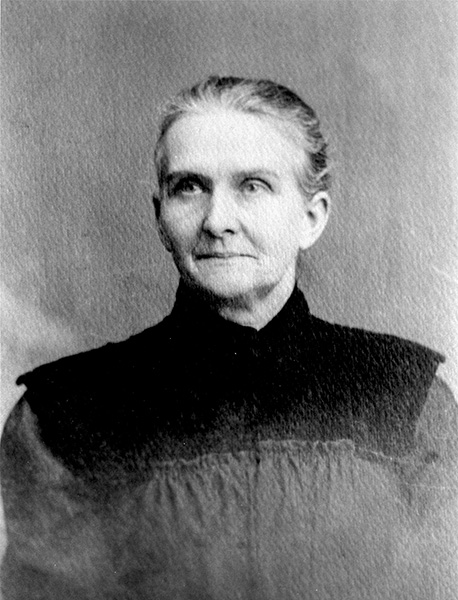

But they wrote letters. The first letter she received from England bore the awful news that her sister Catherine had died. She continued to write to her sisters Ann and Frances until her poor eyesight made it impossible. Teresa insisted that her daughters learn to read and write, and when she could no longer write to her sisters, her daughter Mary wrote.

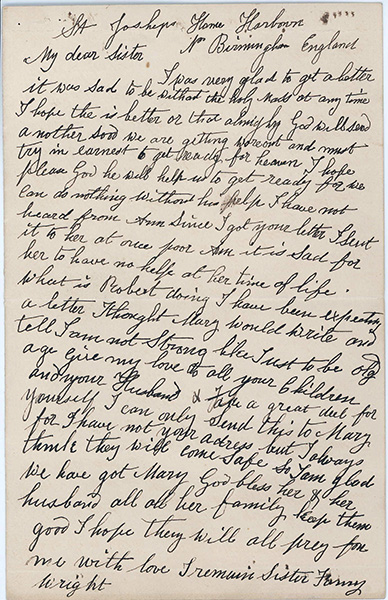

Her sisters in England directed the letters to Mary, knowing that she would share them with her mother. We know this because Mary (and her daughters and their daughters) saved the letters. One of them from Teresa's sister Frances reads, "Give my love to all your Children and your Husband. Take a great deel for yourself. I can only Send this to Mary for I have not your adress but I always think they will come safe. So I am glad we have got Mary. Bless her & her husband all [and] all her family. Keep them good. I hope they will all prey for me."

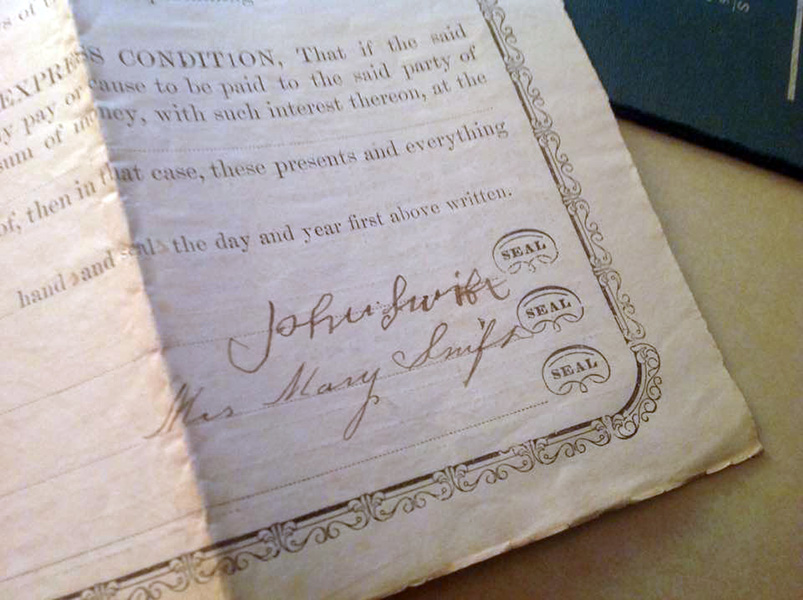

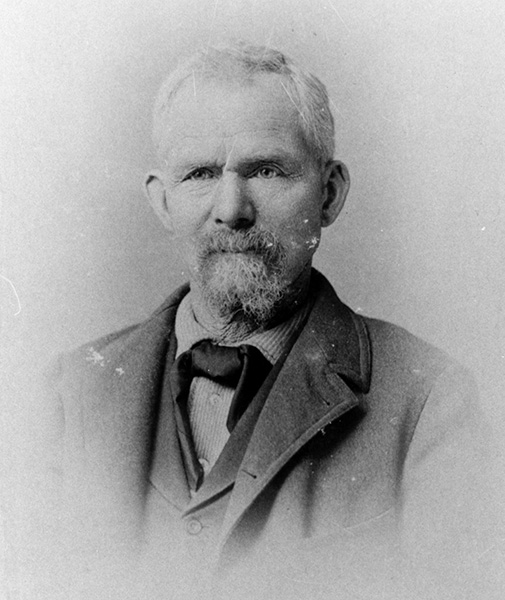

At age 18, Mary Rimmer married an Irishman named John Connell Swift. He could not read and write – only enough to sign his own name, but Mary helped him with those matters, including understanding what the deed said when he bought some land in Iowa, and they moved away from Mary's mother.

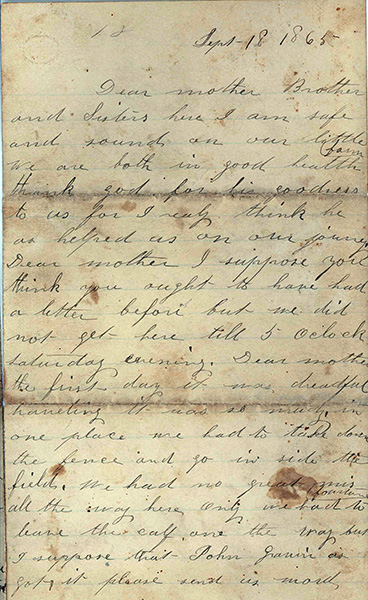

I know about Mary and John's journey to Iowa because she wrote a letter to her mother, Teresa, who was still living in Illinois. "Dear Mother, it was quite a sight for me to see the Mississippi river. It was dreadful hard traveling after we cross it for it was so sandy." And, "Dear Mother, we stayed with an old women the last night and she looked like you said you would when I came to see you."

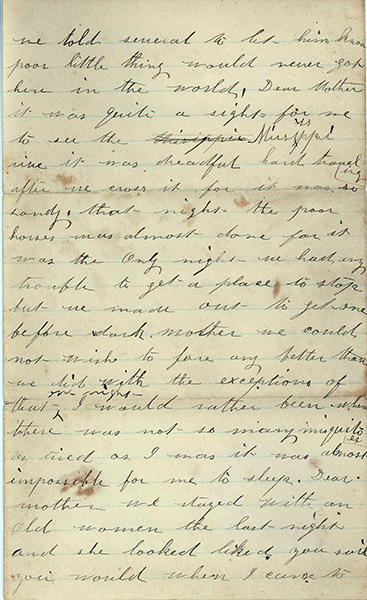

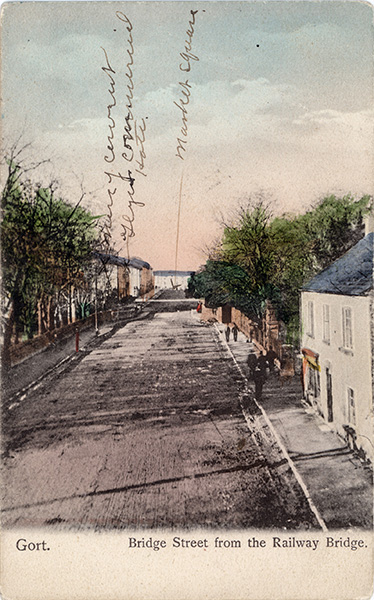

Mary also helped preserve information about John's exact birthdate, a point which he and his brother Martin disagreed on. Martin insisted John was born in 1833 and John thought it was two years earlier. Not wishing to listen to the brothers argue endlessly about the matter, Mary wrote to the priest of Kiltartan parish, Gort, County Galway, and he replied with a statement in Latin and English regarding the date of John's baptism. Were it not for that piece of paper, our family would probably not know the year of his birth because it occurred before church and civil records (for Catholics) were kept.

Mary and her husband, John Connell Swift, had a large family – including nine daughters. And they insisted that they go to school and learn to read and write – still a very unusual idea at the end of the nineteenth century.

So my grandmother, Martha, and her sisters were raised with this appreciation for written language. They kept notes, they wrote letters, they read the newspaper, they saved clippings, and – God bless them! – they wrote down what their parents told them about their ancestors and their lives in the old country.

My great aunts Martina and Kate especially started making notes about the family relations – their cousins' names and their children, their aunts' and uncles' names, their grandparents' names, and so on. Sometimes it was just the tiniest bit of information that their father might tell them about the family in Ireland – that he had an uncle named Patrick, one named James, a first cousin in this place, and so on.

Aunt Martina wrote it down, starting in 1909, when she was living at home with her parents in between teaching jobs. She described how she got started, "It was during this winter that Dad, Mother and I had long talks about their earlier years. It had been forty-four years since they first came to Iowa. Dad would explain the tree planting, the quarry he got the rock for the cellar and well, the trips to Perlee, and about his relatives. It was the same with Mother and it was only natural that it was then that I bought a five-cent note book and began my genealogy note taking. My, but it has been updated so many times. The family has long since outgrown the original nickle note book. Inflation has outgrown the nickle note book, too."

Years later, she gathered her notes and wrote her memoirs, now in a bound book that I consult on a regular basis.

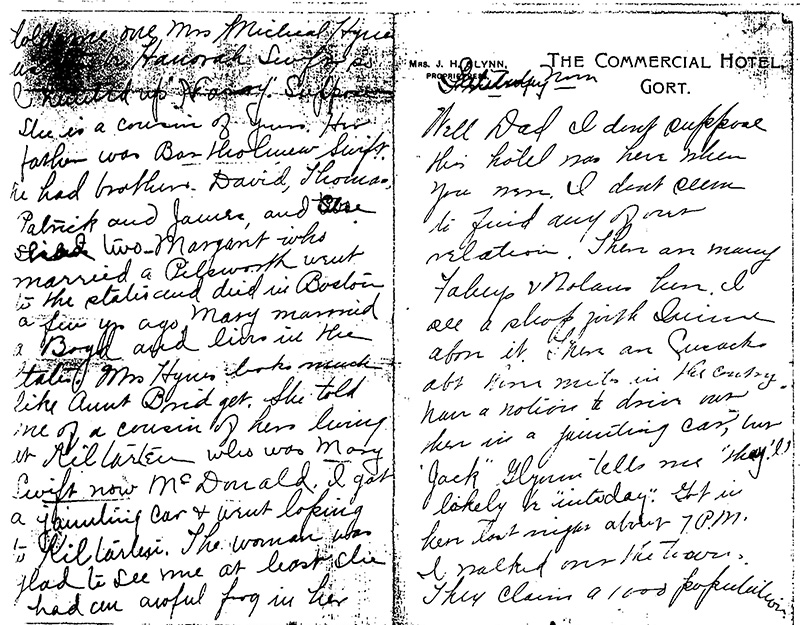

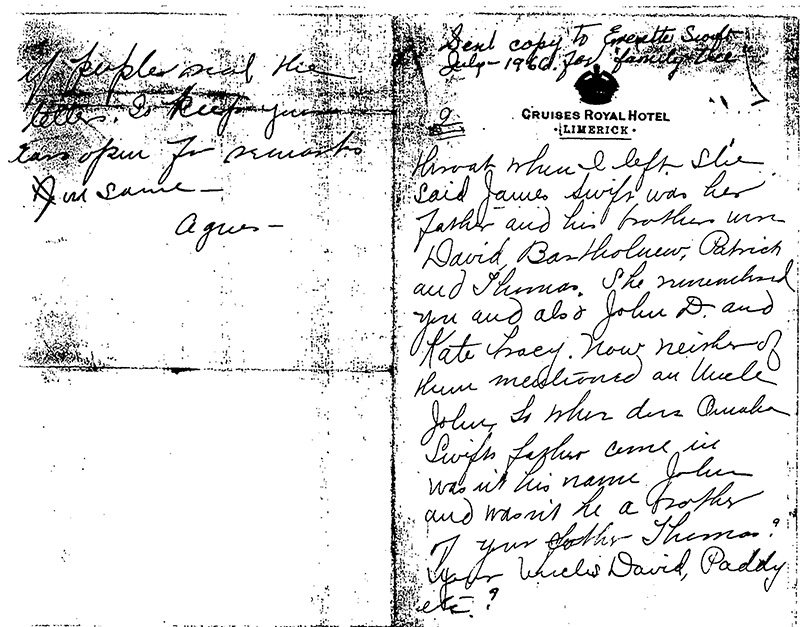

Martina's sister, my great aunt Agnes, was another letter writer. She was prolific, particularly given that she had a busy life as a trained nurse. In 1911, she was invited to travel to Europe with a doctor, his wife, and another nurse. During that trip she took a day to visit the village of her father's birth.

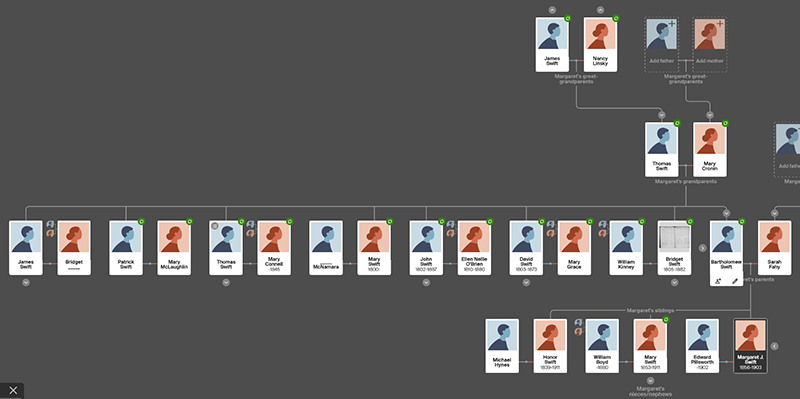

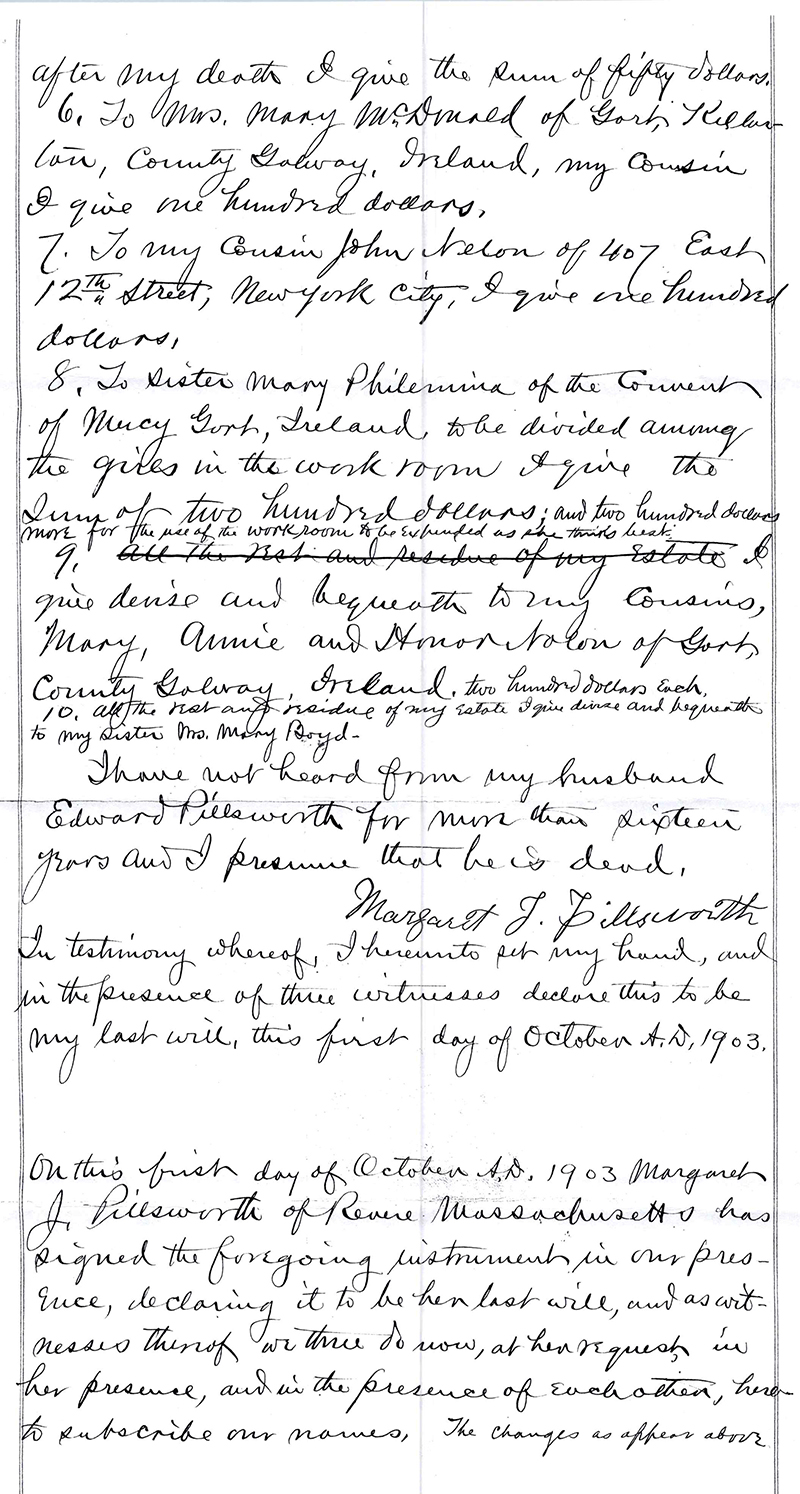

And the end of that day, she sat down and wrote her father about it – how she met his first cousins: "A Sister [of the Sisters of Mercy convent] told me one Mrs. Michael Hynes, used to be Hanorah Swift, so I hurried up. Suppose she is a cousin of yours. Her father was Bartholomew Swift. He had brothers David, Thomas, Patrick and James, and he had two [other daughters] – Margart who married a Pilsworth went to the States and died in Boston a few years ago. Mary married a Boyd and lives in the States. Mrs. Hynes looks much like Aunt Bridget. She told me of a cousin of hers living at Kiltartan who was Mary Swift now McDonnell. I got a jaunting car and went looking to Kiltartan. The woman was glad to see me at least she had an awful frog in her throat when I left. She said James Swift was her father, and his brothers were David, Bartholomew, Patrick and Thomas. She remembered you and also John D. and Kate Tracy."

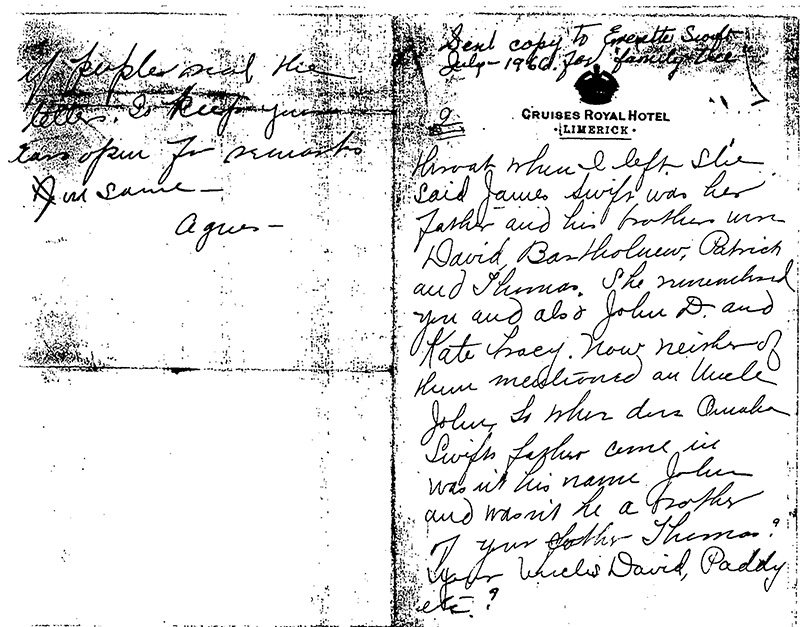

Which brings me back to the rabbit hole I dived into this week. I was looking for my great-grandfather's first cousin, "Margart Pilsworth" who died in Boston. I have looked for her before, but this week, I found her. Or, at least I found her death certificate and now know a little bit more about her.

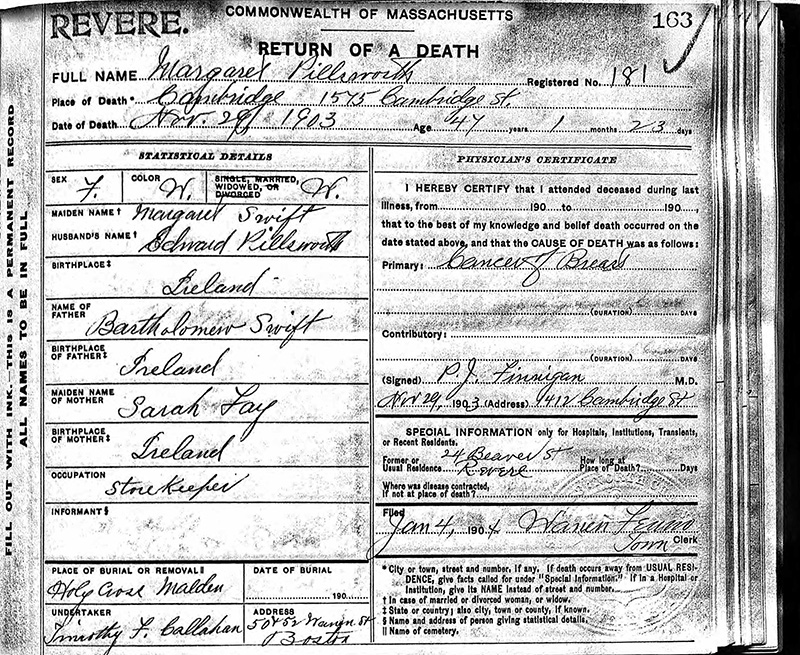

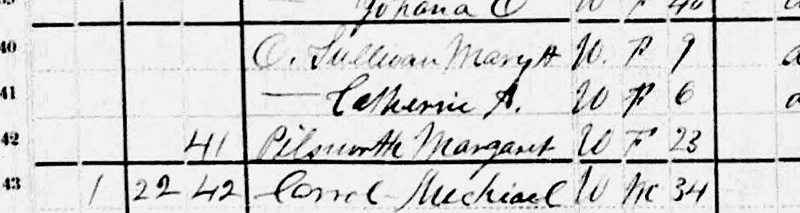

Her death certificate states that she died in the hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts on November 29, 1903 and includes the names of her parents: Bartholomew Swift and Sarah Fay. And her occupation: Storekeeper. And the cause of her death: breast cancer. She was only 47 years old. Widowed. Her husband's name was Edward Pillsworth. She appears in the 1880 US Census, living in a boarding house at 39 Everet Street, Boston, MA, a neighborhood in the shadow of Boston's Logan Airport today. She is described as married but is listed by herself (i.e., no husband, no children). Her name appears on a list of second-class passengers on board the ship New England, returning from Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland, and Liverpool, arriving in Boston in April 1900. Her nationality is noted as "American," indicating that this is not her first voyage to the U.S. since she would have applied to become a naturalized citizen after first emigrating from County Galway. I do not know when she first came to America, but it was before 1880 since she appears in the U.S. Census that year, living in Boston.

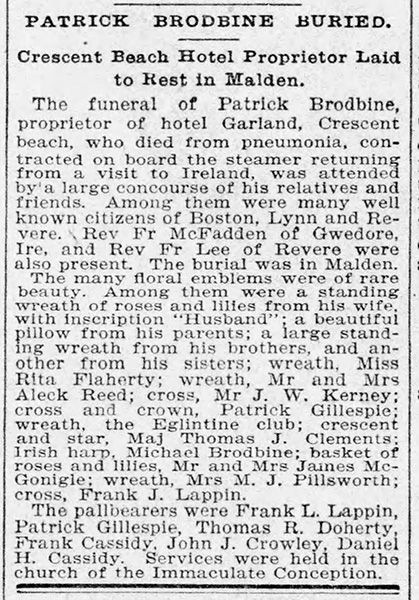

Her name appears in the newspaper in 1901 when she is moved by the death of a friend, Patrick Brodbine, a fellow Irishman and proprietor of the Hotel Garland, and she is listed among the mourners.

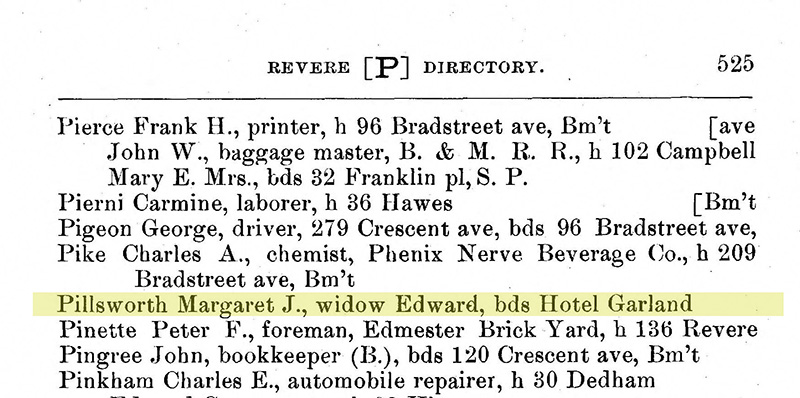

I also found her name in the 1902 city directory of Revere, Massachusetts, listed as a widow of Edward, and living at Hotel Garland. (Note: Cresent Beach is described as the "first public beach in the United States." First known as Chelsea Beach, its named was changed to Crescent Beach in 1881 and became Revere Beach when it opened in 1896. The Hotel Garland was located on Ocean Avenue, the beach-facing boulevard which was a popular gathering place at the turn of the century. After years of decline starting in the 1950's when the beach properties fell into decline, a reclamation process began to restore the beach for safe recreational use. See the website for today's Revere Beach at https://www.revere.org/revere-beach.

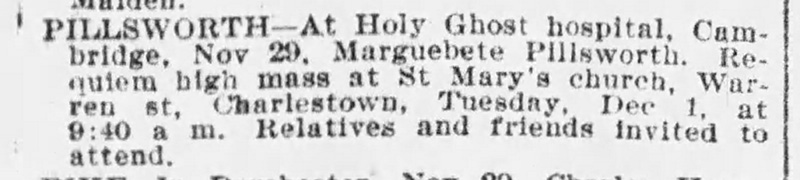

Her death record indicates that while she died in the Cambridge hospital, her usual residence was 24 Beaver Street, Revere, MA. A requiem high Mass was read for her at St. Mary's church on Warren Street in Charleston (Boston), MA, and she was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Malden, MA.

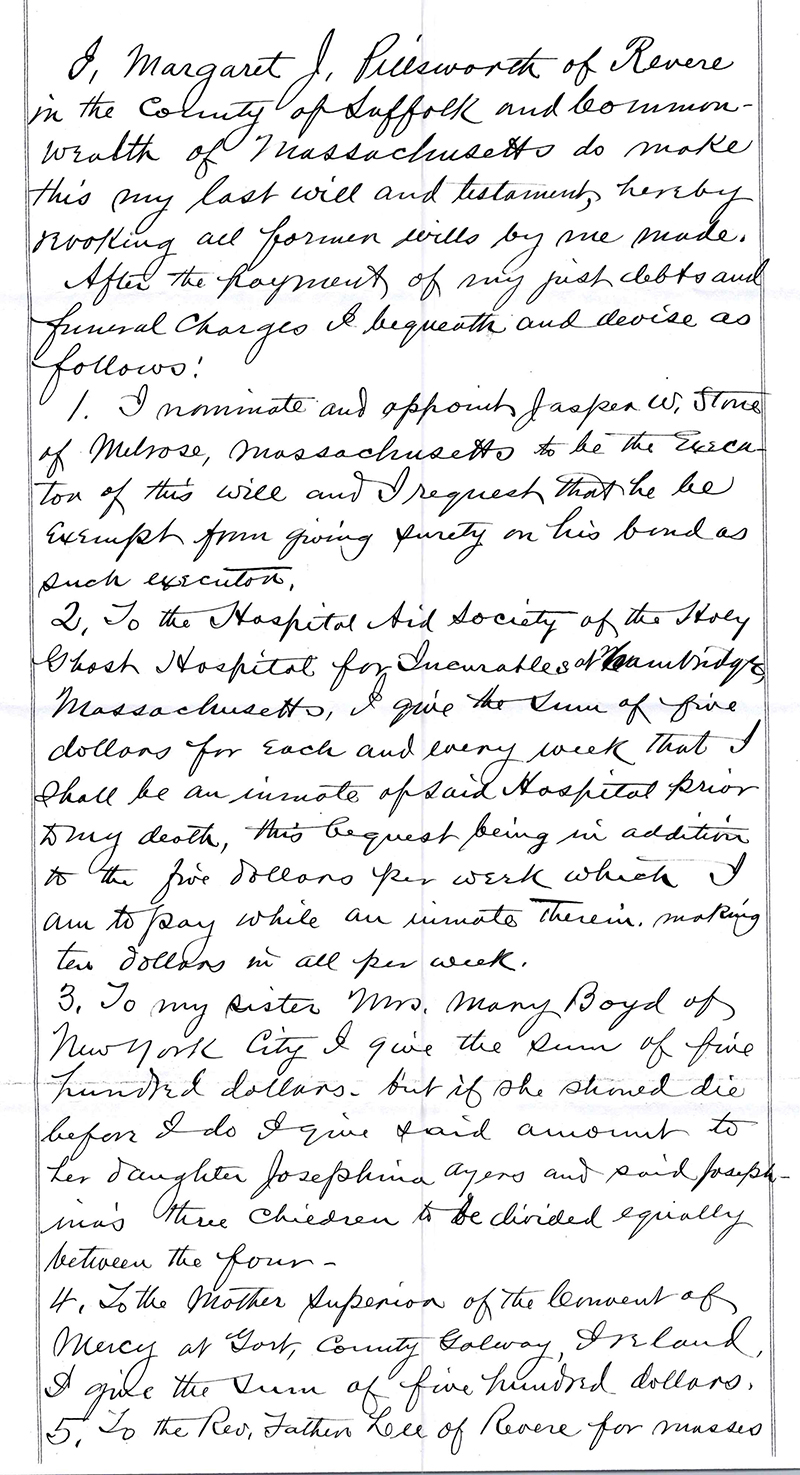

An index of probate records for Middlesex County, MA, indicates that her will was filed in 1903, suggesting that she was a woman of means sufficient to leave something behind. I have written to court officials in Middlesex County for a copy of the will. I hope it will lead me to another rabbit, such as Margaret's sister Mary, who "married a Boyd" and "lived in the States."

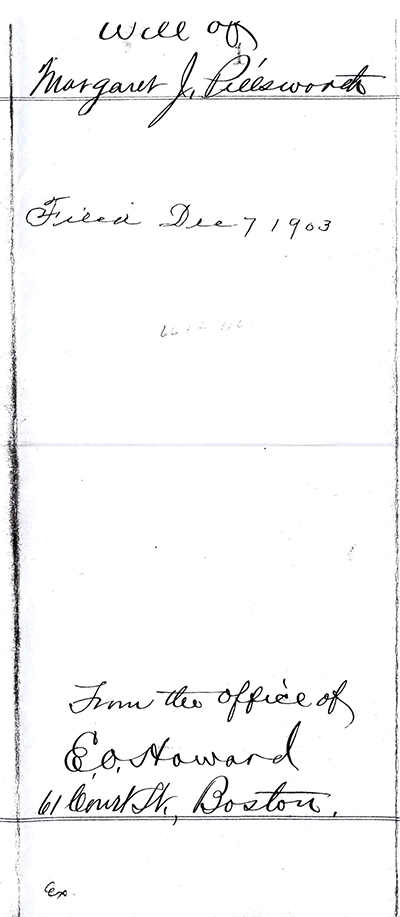

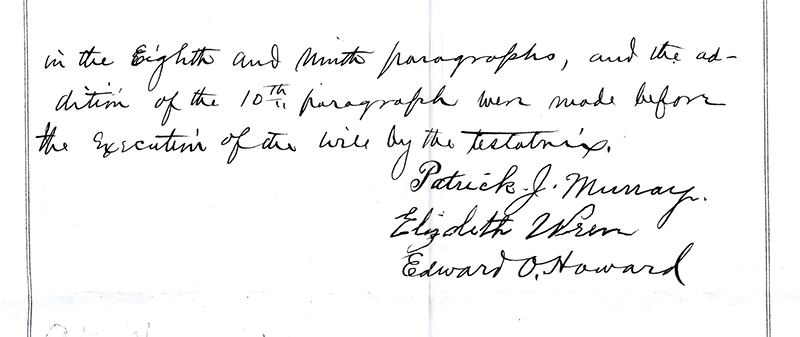

Update, April 25, 2023: After waiting a couple of months and sending a second requsest to Massachusetts for a copy of the probate records of Margaret J. Pillsworth, I received a packet of papers which included a copy of her will and the final decree of the probate court. A copy is reproduced below.

Sadly, the final decree of the probate court was the finding that "it appearing that the estate of the deceased, other than said trust property, is insufficient for the payment of her debts, legacies and charges of administration," her executor was authorized to sell her property to satisfy the terms, leaving "the sum of one hundred and ten dollars to the respondents, and the sum of one hundred and fifteen dollars to the petitioner." Nevertheless, the information from these documents is invaluable to me as it has already allowed me to make connection with some of Mary Swift Boyd's living descendants.